Beware of plutocrats speaking of Spaceship Earth

— Eddie Yuen

LAWRENCE, Kansas — The “great acceleration” of our global environmental crisis — one so often condensed into the language of climate change and prescribed a restorative diet of local organic food, shuttering of polluting coal plants, and minor personal austerities like raising of thermostats — has become increasingly hard to duck.

Recent headlines noting the passage of 400 parts per million CO2 in the atmosphere came with necessarily challenging quotes from activists and scientists. One NASA scientist, for example, compared the fact of industrially produced greenhouse gases now at concentrations not seen on earth in more than 2.5 million years and locking in a warmer, possibly unsurvivable, future, to someone leaping off a ski lift onto a “double black-diamond run without having learned to ski first.”

Concludes Dr. Gavin Schmidt of our destabilized age: “It’s going to be a bumpy ride.”

While global challenges are by no means limited to climate change (there’s the potential pesky collapse of entire ecosystems, like the oceans, for instance), thanks to the rapidly improving science of climatology it’s become increasingly easy to draw straight strong lines between rising CO2 levels and future chaos. Less heard from the front lines of the global environmental crisis has been the parallelling global distribution crisis, according to Rob Nixon, Rachel Carson & Elizabeth Ritzmann Professor of English at University of Wisconsin-Madison and author of Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor.

While global challenges are by no means limited to climate change (there’s the potential pesky collapse of entire ecosystems, like the oceans, for instance), thanks to the rapidly improving science of climatology it’s become increasingly easy to draw straight strong lines between rising CO2 levels and future chaos. Less heard from the front lines of the global environmental crisis has been the parallelling global distribution crisis, according to Rob Nixon, Rachel Carson & Elizabeth Ritzmann Professor of English at University of Wisconsin-Madison and author of Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor.

At the opening plenary session of the biennial conference of the Association for the Study of Literature & the Environment in Lawrence, Kansas, today, Nixon sought to mend that gap.

As humanity seals its place on the planet as a force of geology and the warm interglacial period known as the Holocene gives way in an increasing number of scientific papers to the Anthropocene, an only recently coined term offered as a nod to humanity’s increasing impact on earth systems, most notably the climate, Nixon sought to co-saddle our “New Human” era with an “Age of Disparity.”

While holding out the possibility that the term “anthropocene” could “reanimate notions of human responsibility,” Nixon recognized it also poses policy risks for a species already prone to narcissism. Such self-absorption is present in the attitudes of those who advocate a rapid technological fix for climate change such as seeding the ocean with iron filings or launching solar blocking devices into orbit around the earth. Astrophysicist Lowell Wood, for instance, has famously said, “We’ve engineered every other environment we live in — why not the planet?” And Mark Lynas writes in The God Species: Saving the Planet in the Age of Humans matter-of-factly, “Nature no longer runs the Earth. We do.”

“When I read words like that,” Nixon said, “I can see Icarus’s wax melting as he plummets from the sky to the sea.” Geoengineering, he said, should be reserved for a time we understand the earth’s systems “a lot better than we do.”

While there has been a lot of talk about putting the brakes on climate change, a stunning facet of the anthropocene era, far less attention has been given the concurrent stranding of oceans of humanity in extreme poverty, most starkly visible in the mega-slums ringing so many of the world’s largest cities (that’s Jakarta at top, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

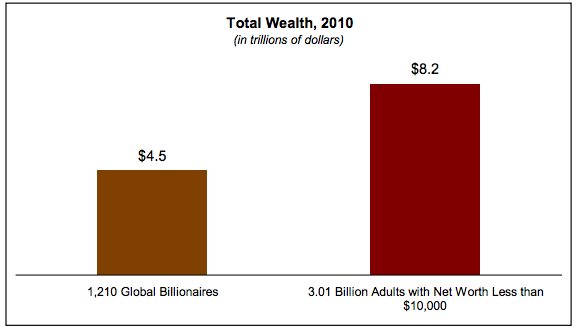

Viewed statistically, as Forbes reports: the world’s 1,200 billionaires have a combined wealth equal to more than half the combined wealth of 3 billion global adults who hold, according to Credit Suisse, less than $10,000 in net worth each.

When addressed by environmental organizations, the rise of the mega-slums have been attacked as examples of population pressures run amok. However, Nixon suggests the problem lies elsewhere. “Some people would see in these images overpopulation, what I see is atrociously distributed access to life’s resources.”

With 80 percent of the planet’s human population expected to live in urban environments by 2050, these “sacrifice zones” betray our inability or unwillingness to make sure the earth’s resources are distributed more equitably.

While individuals have very little say in either slow-moving global tragedies (“No matter how many times you change your lightbulbs and sort the garbage, that is insufficient,” Nixon said), governments — increasingly in the thrall of the transnational corporations — are unlikely to move without a resounding clamor.

Nixon opened his talk with a video clip of naturalist David Attenborough introducing the creature that has come to imitate not only the distant cousins in its broader feathered family, but of cameras and chainsaws, as well. Nixon wondered if the chainsaw song was “some premonition of the ultimate silent spring.”

There is undoubtedly a human cruelty inhabiting this unique performance. And there is also likely a warning here as significant as the CO2 readings taken at Mauna Loa. Our natures — one an accumulating force expanding exponentially through globalization, the other an animal still capable of divining the message of birdsong — are locked in suicidal conflict.

To correct our global imbalances, we must also be prepared to resist oil and gas interests, transnational corporations, as well as our own reluctant leaders, Nixon suggested. As with our competing individual selfish and selfless natures personified in the Cherokee legend of the two wolves, the victor will likely be the force we choose to feed.