Greg Harman

You can call it bragging rights. For years, San Antonio policy makers and elected leaders have made a lot of hay out of the fact that San Antonio was one of the last large cities in the United States still in compliance with federal ozone standards. That appears to be about to change, and the explosion of oil and gas development across the Eagle Ford formation of South Texas is a key culprit.

All told, ozone precursors such as nitrogen oxide produced in the Eagle Ford’s oil and gas development will likely soon equal the amount currently released in all of Bexar County, Peter Bella, natural resources director at the Alamo Area Council of Governments, told audience members at Thursday’s air-quality forum “Keeping It Clean: Our Air, Our Health.”

The discussion was hosted by the Mission Verde Alliance and the San Antonio Clean Technology Forum.

Preliminary data collected by AACOG and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality suggests the multi-county shale play could raise ozone levels in San Antonio as high as 7 parts per billion. The current federal standard for ozone is 76 parts per billion over a rolling three-year average. San Antonio violated that average by shooting past two years at 75 ppb in 2010 and 2011 to hit 80 ppb in 2012.

An audience member asked Bella what kind of changes rising ozone levels will require from San Antonio residents hoping to avoid the increased health impacts as well as the economic punishments that come with non-attainment status. Bella declined to speculate.

“These are projections, draft data,” Bella said. “It does suggest the potential for a magnitude of impact that is very important.”

The projections fit with what other areas of fracking activity have experienced.

A year ago, Bloomberg news reported:

Wyoming’s southwestern region was found to have an unsafe level of smog-causing ozone for the first time, a designation the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency linked to a boom in oil and gas drilling in the state.

The EPA included the Upper Green River Basin in its list of areas nationwide exceeding a federal ozone limit. Until today, Wyoming was the only state where all counties had met the federal ozone limit.

“The growth in the oil and gas industry, which has been explosive in the last few years, is the place we need to look for answers,” Bruce Pendery, staff attorney for the Wyoming Outdoor Council, said in an interview. “This will force the state to take significant steps to clean up the air.”

Similar findings were reported in Colorado earlier this year.

Emissions from oil and natural gas operations account for more than half of the pollutants — such as propane and butane — that contribute to ozone formation in Erie, according to a new scientific study published this week.

The study, the work of scientists at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado, concluded that oil and gas activity contributed about 55 percent of the volatile organic compounds linked to unhealthy ground-level ozone in Erie.

Key to the findings was the recent discovery of a “chemical signature” that differentiates emissions from oil and gas activity from those given off by automobiles, cow manure or other sources of volatile organic compounds.

Of particular interest in North Texas’ Barnett Shale has been the powerful ozone precursor formaldehyde.

Jay Olaguer, director of air quality research at the Houston Advanced Research Center, presented his analysis of the industry report last week, suggesting formaldehyde levels were being regularly underestimated. The industry blowback on Olaguer was significant enough for the researcher that he asked the Current to submit all questions in writing.

Formaldehyde readings of the Titan study — which, in the above referenced case, reached 126 parts per billion — were “astoundingly high,” Olaguer replied by email. “I’ve never heard of ambient [formaldehyde] concentrations that high … except in Brazil where they use alternative fuels such as ethanol and gasohol for automobiles.”

And yet what industry is actually putting into North Texas skies could be up to a hundred times greater than even the Titan study suggests. At least that’s what HARC teams found when they used more advanced sampling techniques to sniff out the Houston Ship Channel in May of last year.

Aside from potential public-health impacts of formaldehyde (which can cause difficulty breathing at levels above 100 ppb and is a suspected cancer-causer, according to the EPA), the chemical is also a “powerful radical precursor” that jumpstarts the creation of ground-level ozone.

How powerful is it?

Olaguer writes of a recent case in Wyoming: “It was discovered that there are severe ozone exceedances in the middle of winter (long thought impossible) over the Jonah/Pinedale oil and gas fields. After I informed Wyoming DEQ of the SHARP study results that implicated formaldehyde as an under-reported radical and ozone precursor, they commissioned a fast-turnaround study by TRC to look at the impact of formaldehyde emissions from drill rig engines on wintertime ozone. TRC found that when they put those emissions in (there were none at all previously), wintertime ozone over the gas fields spiked enormously.”

While the air impacts are not unexpected, Bella’s ability to finally put a number on it — preliminary as they are — is new. Of course there are public health ramifications beyond San Antonio’s city limits not discussed at the forum.

But SA Metro Health Director Dr. Thomas Schlenker shared a few horror stories from history — including the Great Smog of 1952 during which coal pollution was trapped close to the ground for five days, resulting in an estimated 12,000 deaths — to drive home the point that ozone kills.

The American Lung Association considers ozone the most widespread and one of the most dangerous air pollutants in the U.S. It forms when nitrogen oxide, hydrocarbons, and carbon monoxide — products of the combustion of traditional petro-based fuels — combine in the air during periods of high heat.

Short-term exposure is blamed for breathing difficulties, respiratory infections, inflammation, and asthma attacks, while longer exposure has been linked to early death — even at levels considered safe under today’s standard.

While the EPA ruled San Antonio was still in attainment under the 2008 standard in April of 2012, new tougher standards with the strong support from the public-health community are more than likely on the way also.

Former EPA Director Lisa Jackson recommended lowering the ozone standard to 70 parts per billion. Her move was rebuffed by Obama’s White House.

It’s a move that has the support of the medical community and will more than likely become the law of the land — if not a more stringent figure — said Elena Craft (right), health scientist with the Environmental Defense Fund’s Austin office. So even if San Antonio can ratchet its contributions down, the potential new regs and rising Eagle Ford emissions pose a seemingly insurmountable challenge.

CPS CEO Doyle Beneby recognized the public-health impacts of the utility’s coal plants, which helped inform the decision to shutter JT Deely’s two coal-fired units in 2018 — emission-wise the equivalent of taking a million cars off San Antonio roads, he said.

Beneby (below) stressed the move was a voluntary one. “We could keep going by switching to ultra low-sulfer coal,” he said. “To a lot of people the notion of climate change is an abstraction … but we have people around us whose health is affected by our cars and our power plants.”

Craft repeatedly returned the conversation to policy shortcomings at home, such as the large amount of coal CPS Energy still burns as compared to other large Texas cities.

“Currently San Antonio is using more coal than what the average in Texas is, as well as what the average in the United States is,” she said.

And, she added, state oversight of oil and gas could be much more stringent.

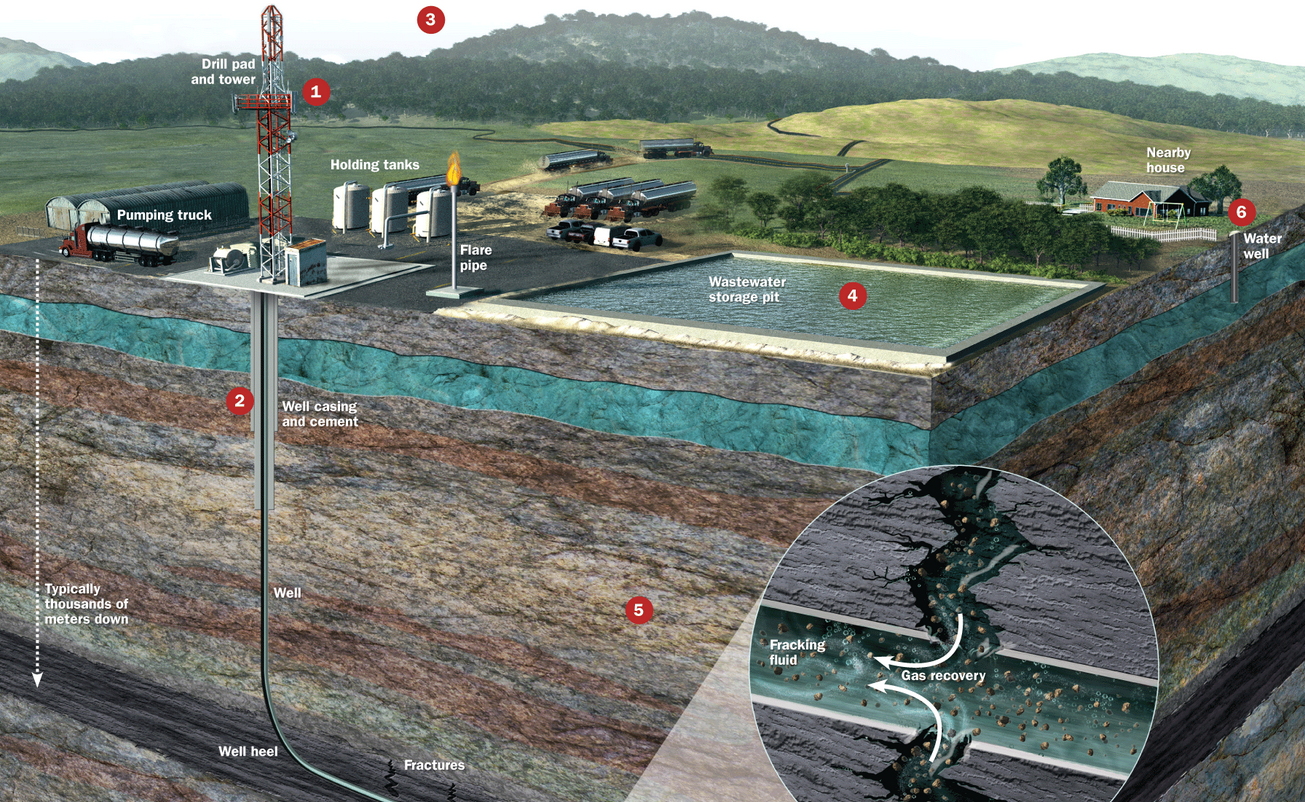

In a fracking play that is still primarily about the shale-trapped crude oil, only 44 percent of well completions in the Eagle Ford capture the natural gas emissions that come to the surface rather than flaring them into the air.

“It makes no sense not to collect every bit of product,” she said. “We can do a lot better.”

“A lot better” will be what is required of San Antonio. Repeated by nearly every panelist as well as Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff in his introductory remarks is the need to cut down on the large amount of suburban traffic, the encouragement of inner-city development, and creation of strong multi-modal public transportation options.

“We’re coming very close of hitting non-attainment and all the economic consequences of that,” Wolff said. “We’ve gotten a little bit complacent, there’s not been much talk about it lately. We’re all going to need to pull together.”