But That’s No Reason Not to Fight Oil & Gas Development on Both Sides of the Rio Grande.

Trampling of landowner rights. Failure to consult native tribes. Soiling a cherished Big Bend with oil and gas development. Risk of explosion and fire.

All are convincing, and oft-repeated, reasons for opposing Energy Transfer Partners’ Trans-Pecos Pipeline now carving its way toward the Rio Grande in Far West Texas. From there it is expected to cross the international boundary and tie into Mexico’s expanding natural gas infrastructure.

There are more arguments besides that are frequently identified by those fighting the pipeline, opposition that has garnered five arrests, to date, for strategies involving direct action.

The threat of future industrial expansion. The illogic of tapping more methane-emitting natural gas with a planet in climate peril. The arrogance and cruelty of a company that condones the continued militarized violence against native peoples in North Dakota simply for trying (non-violently) to defend their water supply at Standing Rock. The U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s refusal to conduct a full Environmental Assessment to best determine the safety of the 143-mile pipeline.

Yet one mantra of water protectors should probably be retired. Some continue to suggest conspiratorially that the gas isn’t for Mexico—it’s for Japan.

The roots of this assessment are due, at least in part, to a 2016 report at Truthout, where the author argued:

The gas in the pipeline is not intended for Mexico, as both ETP and Carlos Slim would like the public to believe. It is in fact intended to be shipped overseas, which of course also means that their use of eminent domain (the right of a government or its agent to expropriate private property for public use) to seize land in Texas has been and continues to be illegal.

The principle financial backers of the project include the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi and the Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation in Japan, according to reports from within the oil and gas industry itself.

With Japan continuing to reel from the ongoing effects of the Fukushima disaster, that country is moving to shut down all of its nuclear power and is currently replacing that energy with natural gas, thus driving gas prices dramatically in both Japan and other parts of Asia.

There are serious problems with this assessment, including, perhaps most obviously, the fact that Mexico desperately needs new energy sources and is banking on meeting its robust climate-change commitments with the expanded use of natural gas.

But start with the supposed end-of-the-pipe customer.

Japan is definitely not “moving to shut down its nuclear power.” Just the opposite. Despite organized protest urging a rapid transition to truly renewable (and safe) fuel sources, the country is actually starting to turn some of its 50-odd nukes back online as the triple nuclear meltdown and explosions of 2011 begin to fade from memory.

While it’s true all of Japan’s nuclear plants were idled soon after what is regarded as one of the worst nuclear disasters in history, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has put Japan back on course to meet nearly a quarter of electricity needs with nuclear power, and within three years. Already at least five of its nuclear power plants have returned to service.

Although Japan has been one of the largest importers of liquified natural gas in the world, those import’s are beginning to decline, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The United States, a steady supplier of LNG to Japan for some years, has has begun to throttle back, with LNG exports to Japan falling from 30 billion cubic feet in 2010 to just over 8 billion in 2015. Japan’s slight reductions, however, don’t reflect the trend among its neighbors. Though it’s highly unlikely Mexico will be the one to fill those purchase orders, at least anytime soon.

Despite having robust oil and gas fields, Mexico is an energy poor state. While the country’s largest export is crude oil (9 percent of all exports); it’s largest import is refined petroleum products. Essentially, the nation has unrefined crude—crude that is regularly siphoned off by criminal networks—it is unable to convert for domestic use. Thanks to energy deregulation ushered in several years ago, it’s a trend that is expected to continue.

While Mexican crude oil is exported increasingly to Asia (Japan included), the refined product it needs to grow its economy is used at home. If you doubt the crush of domestic power needs in Mexico, just survey the scene of national riots over gas prices, which the Los Angeles Times termed “open rebellion,” over a 20-percent price hike tied to deregulation.

This is beautiful Mexico, stand strong and stubborn. #gasolinazo pic.twitter.com/ul5VBYNlWk

— 🐞 (@biizzzyybee) January 16, 2017

“The increase in pipeline projects,” writes Bloomberg news, “is driven by Mexico’s desire to replace fuel oil for power production as well as the country’s demand for a low-cost fuel for industrial use.”

Of course, that’s not the full story.

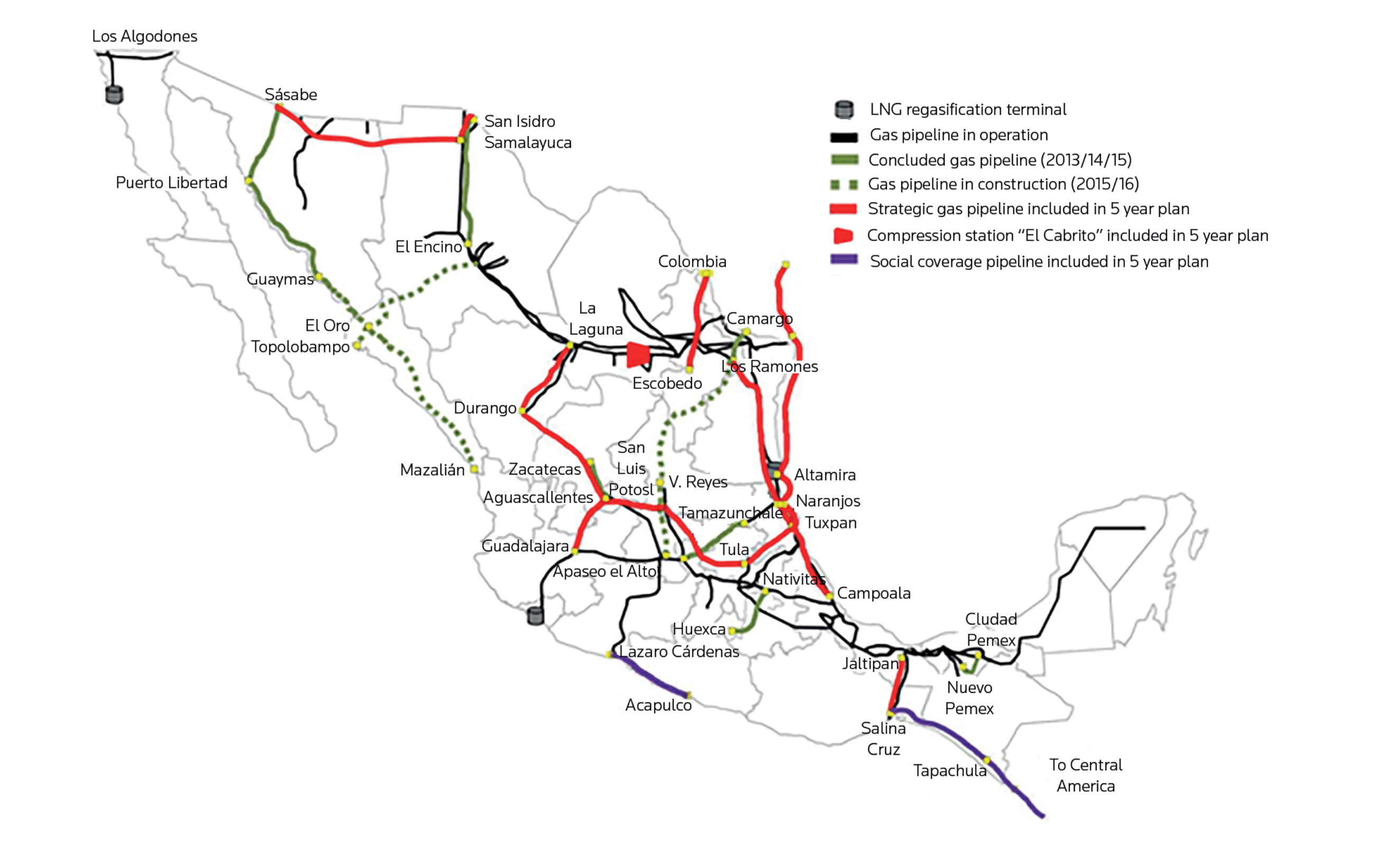

Mexico’s Department of Energy’s five-year plan for energy reform projects (2015-2019) has focused on the enhancement and expansion of natural gas infrastructure across the country, including feeding U.S. resources into a network of existing pipelines in Northern Mexico. New lines in the states of Chihuahua, bordering Far West Texas, and Tamaulipas, which run alongside South Texas, and Nuevo León, are expected to be finished in the next couple of years, according to the plan.

Through these new lines, the Mexican government hopes to triple the amount of natural gas it imports from the United States by 2019. Natural gas imports from the United States have doubled just since 2009, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The line from San Isidro, Mexico, would run 23 kilometers to a natural gas/diesel power plant, the 925MW Norte III Combined Cycle Power Generation Plant, to be the largest such plant in Mexico and expected to go online this year. All told, the plant could power more than 2.5 million homes. Construction of Norte III is being led by Abengoa, the Spanish firm the San Antonio Water System had contracted with for a massive water pipeline only to switch partners when the Abengoa’s huge financial liabilities came to light.

From thereabouts, an additional line is to run 650 kilometers to Sasabe. Together with already operating border-crossing pipelines in South Texas, the crossings and related infrastructure represent a $16B investment by the Mexican government and tally up to 3.5B cubic feet of gas entering the country—primarily from Texas—per day.

These are imports.

Mexico is already the largest LNG customer for Peru and is taking on more LNG from the United States. Even the pipelines being constructed to Mexico’s coast tie into import terminals. Terminals like one intended to bring Korean LNG to Mexico.

You can see two LNG regasification ports on the below pipeline map, showing where liquified gas carried by ocean tankers is converted back into gas form for domestic use.

The big Mexican story here is not one about as-yet unsupported sleights of hand by ETP CEO Kelcy Warren and Mexico’s Carlos Slim. The pipeline story south of the border (besides pockets of indigenous resistance and countering violent oppression, which I hope to tackle in future posts) revolves around the country’s commitments over climate change.

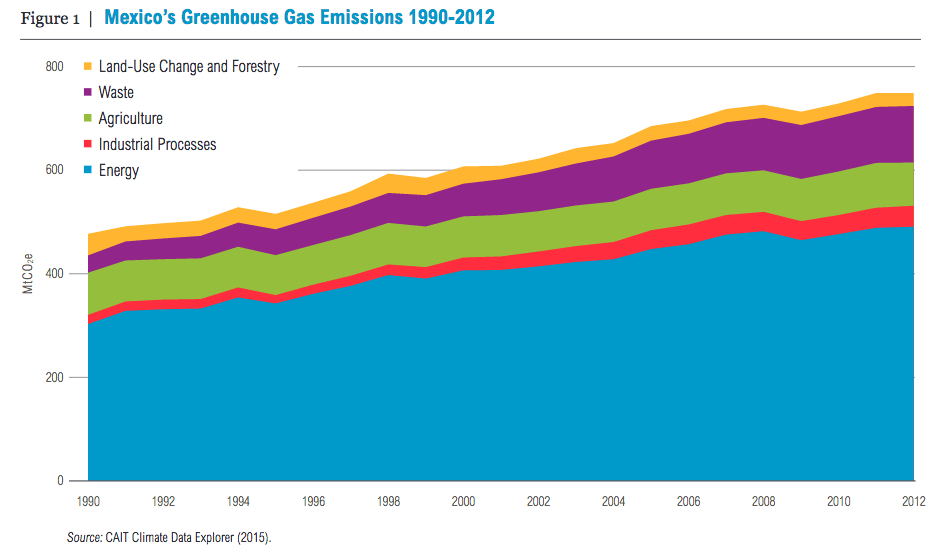

Mexico has committed to reducing its greenhouse and black carbon emissions by 25 percent by 2030 (and possibly, ideally, by much more). A cornerstone of reaching that goal is the replacement of heavy fuels with natural gas. “Clean energy, according to the Mexican government, includes wind, solar, biomass and nuclear, efficient combined heat and power, and thermoelectric plants with carbon capture and storage. In addition, the government plans to increasingly substitute heavy fuels, largely with natural gas,” reports Lillian Sol Cueva.

And, yeah, that’s a problem.

Thanks to the ongoing deregulation of the Mexican energy market, the Open Climate Network reports:

Oil and gas investment projects will increase, with the greater part of investment going to natural gas, unconventional hydrocarbons, and deep-water extraction. The PECC recognizes that this expansion—together with modified procedures to expand the electrical grid—is likely to result in increased GHG emissions from the energy sector.

Still, Mexico is banking on reducing its GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions with “the substitution of natural gas and biomass for heavy fuels” with better policing of “methane leaks, venting and flaring,” OCN states.

Here’s Mexico’s emission history and its intended reductions.

Climate Action Tracker is more directly critical of the inclusion of co-generation involving natural gas as part of Mexico’s energy transition, suggesting it will lead to an overall increase in GHG.

Critically, Mexico includes co-generation in its definition of clean energy. This is likely to be natural gas, which is a fossil fuel, and still emits CO2. National projections suggest that the cogeneration plants’ share of the electricity mix could be as high as 9% by 2030—up from 0% in 2014. If this goes ahead rather than using entirely zero emission sources, emissions would be 58 MtC02e—or 6% higher—in 2030, and could reduce the share of renewables in the 2024 clean energy target to 29%.

Together with the renewable energy support policies that have recently been put in place, opting for zero emission sources instead of co-generation would be an important step in the right direction, but needs to be followed up by further policies for Mexico to reach its INDC target.

Mexico shouldn’t be accused of being complicit in a nefarious plot to ease the way for U.S. energy and Mexican telecom tycoons to shuffle gas sideways to the global market. At least not yet. I’m open to being proven wrong. Consider, though: U.S. oil and gas titans have global access covered, with at least three LNG terminals operating and seven new LNG terminals under construction. They don’t need to wait years to ship gas to Japan through oft-punctured Mexican pipelines traversing across the country.

Water protectors are right to resist the expansion of fracking in West Texas. They are right to resist the expansion of dirty oil and gas at every turn. But the warning to Mexico today is better focused on its likely fumbling of its international commitments to help stabilize the climate with a gamble on natural gas.

That failure comes with many costs, only one of which is the violent expansion of oil-and-gas-fouled sacrifice zones threatening the sacred springs at Balmorhea and the profound majesty of our treasured Big Bend.

-30-

{UPDATE: PEMEX has been promoting its desire to future export projects to potential investors, as seen in this Investor’s Day presentation made in London back in 2014. My thanks to Coyne Gibson for directing me to this document (you can see his comments below). But as I write above, such is unlikely to come anytime soon. If and when this export capacity develops, it won’t come through a dedicated Trans-Pecos line, but via a much broader ramping up of Mexico’s total natural gas infrastructure and trail behind Mexico’s own yawning domestic energy needs. Again: My opinion.}