In the gentle ferocity of Manuel de la O lies a manual for survivance.

Marisol Cortez

This Solstice of 2019, as the earth sinks into deepest cold and dark, and as we close out San Antonio’s “Decade of Downtown,” we recognize Mr. Manuel de la O as Decelerator of the Year.

I met Mr. de la O five years ago, during a year of frantic organizing to halt plans to remove a trailer park from the banks of the San Antonio River. It was the middle of (then-Mayor, now presidential candidate) Julian Castro’s much-trumpeted “Decade of Downtown,” with its push to proliferate housing for the creative class in San Antonio’s center city. Land values were rising as planned, dangling the promise of higher rents to developers near and far. They were rising especially quickly along the river just south of downtown, where just months before, a hike-and-bike trail linking the city’s Spanish colonial missions had opened, helping the city nab UNESCO’s coveted World Heritage designation for the missions. Conditions were ripe for local developers White-Conlee Builders to eye the park as prime real estate, and in early 2014 they petitioned the city to rezone the land for luxury apartments.

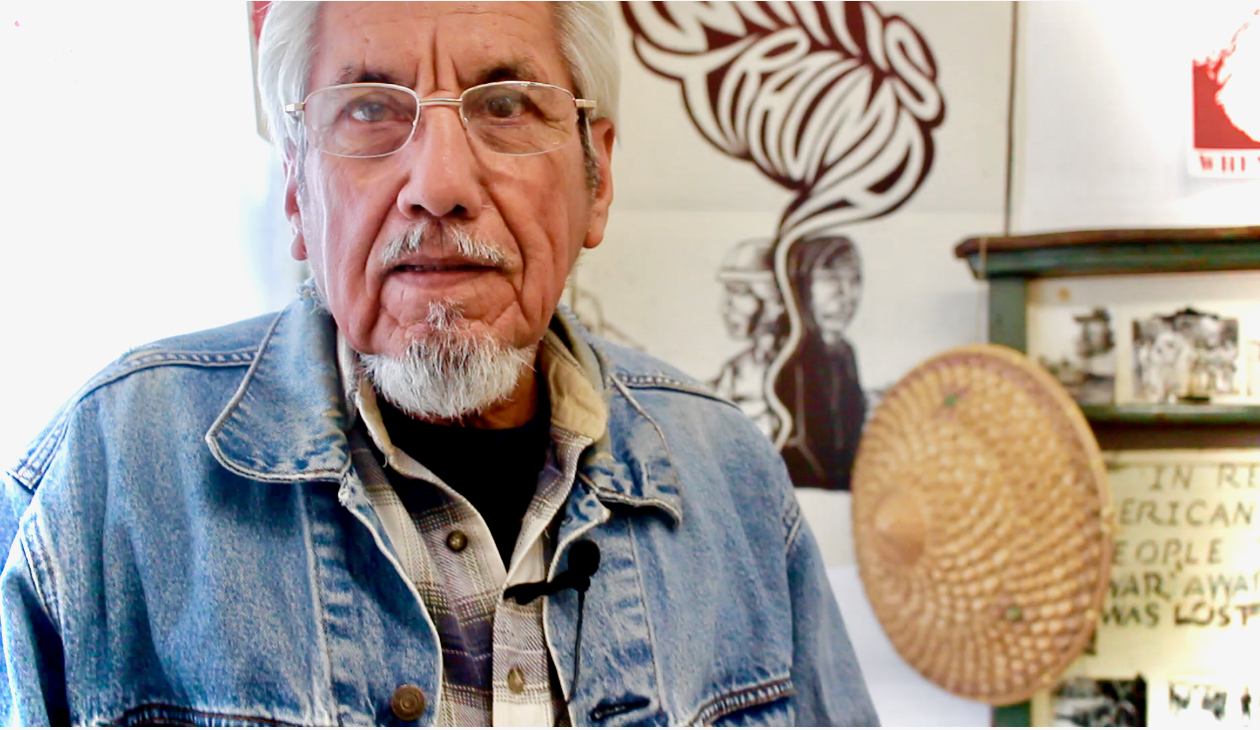

Following the lead of councilwoman Rebecca Viagran, the city rolled over easily enough—though not without a fierce fight by Mission Tails residents. A neighbor seeking to lend my support to resident organizing at Mission Trails, I initially crossed paths with Mr. de la O when I gave him a ride to a city council meeting. I liked him—he was easy-going, a small-framed man in his late 60s with bristly grey mustache, aviator glasses, slicked back hair. Like many of the residents at Mission Trails, he had no vehicle of his own, and he had health conditions that made it hard to get around. I was happy to be able to give him a ride. Later, after the city rezoned Mission Trails and families began their long, traumatic exodus from the park, I got to know Mr. de la O a little better, as he was one of a handful of residents who stayed until the end.

Most folks at Mission Trails had lived there a decade or more, but Mr. de la O had arrived more recently. He’d moved in just a couple years before rezoning began, assuming Mission Trails would be his final home, the place he’d live until death. The park was quiet, shaded by numerous old Spanish oaks and pecan trees. His trailer sat at the back, overlooking the river banks and the winding concrete path the city had built for joggers, cyclists and dog walkers–but not the people who inhabited those banks. Mr. de la O was content, despite his ongoing health issues. He set up a patio outside the trailer, where he placed a table with an umbrella for shade. As a Vietnam Veteran with PTSD and pulmonary fibrosis—a lung condition that hardens the airways and makes breathing difficult—the peace and quiet was important to him. Those of us involved most intimately at Mission Trails never called him Manuel, always Mr. de la O or Sr. de la O, a sign of respect and affection.

Mr. de la O was one of six households who stayed until the very end of the time legally permitted residents following the sale of the park—typically three months, but resident pushback extended this to six months and beyond. As a single man living on his own, Mr. de la O was relatively advantaged, compared to the other residents forced to stay until the end. He had no children to worry about; he was a U.S. citizen; he spoke English. Moreover, as a veteran, he qualified for assistance from the G.I. Forum, which had promised to gift him, for free, a house on the Eastside they were fixing up. Despite these safety nets, almost everything about this plan went wrong before it eventually came to fruition.

The house was not ready by the end of his legal right to stay at Mission Trails, nor was it ready a couple months later, after assistance ran out on a temporary housing arrangement. By that point, the $2,500 the developers had given him for his $8,000 trailer was gone; he’d used it to purchase and fix a van he ended up living in for several weeks, sick and suicidal, before moving in and out of other temporary living arrangements. It was in one of those apartments that I interviewed him in May of 2015, for a report we published in May 2017 as Vecinos de Mission Trails.

After folks were scattered across the city—indeed, the continent—and Vecinos tracked down as many as possible to interview, we lost touch with almost everyone we’d organized alongside for so many months. Mr. de la O was one of the few we stayed in touch with. As Vecinos shifted from documenting the impacts of displacement to pushing city policy to be accountable to those impacts, Mr. de la O would still come out to city meetings and actions—despite being homeless for a year after his removal from Mission Trails, a year that saw him move five times before G.I. Forum finally made good on their promise of a house. When our report came out in May 2017, he was one of just a couple residents who attended the press conference.

He had an activist’s heart: despite the trauma he’d experienced, he understood the importance of telling his story again and again. By that time, he’d been living in his casita for about a year, a one-bedroom bungalow near St. Phillip’s College with a nice, neat yard. He’d invited us over shortly after he’d moved in, and we brought celebratory housewarming tacos. He’d been on hospice for awhile, he told us, but he wasn’t anymore—he’d been deemed too healthy and discharged. We all laughed, incredulous. Surely he meant the hospital? No, no, he said, hospice. None of us had ever heard of someone going into hospice and then getting discharged.

I lost touch with Mr. de la O again after the report came out, this time because I needed to retreat for awhile into ordinary life. Greg and I were trying for trying for a baby and failing, then trying for a baby and succeeding, with all the joyful disorientation and exhaustion which accompanies that success. I thought about Mr. de la O from time to time, wondering about his health, but I figured no news was good news.

Then, with something like delight, I saw him a few weeks back walking into the Galería EVA for the Veterans Resistance Art Gallery, organized by About Face: Veterans Against the War. I was relieved to see that he looked about the same, in his flannel shirt and aviator frames. He was one of the few local veterans to have a piece in the show, a traveling exhibit of screen printing that tours nationally.

Another local artist included Regina Vasquez from San Marcos, whose clothesline project—documenting the voices and stories of military sexual assault survivors—has been exhibited in numerous other exhibits and spaces.

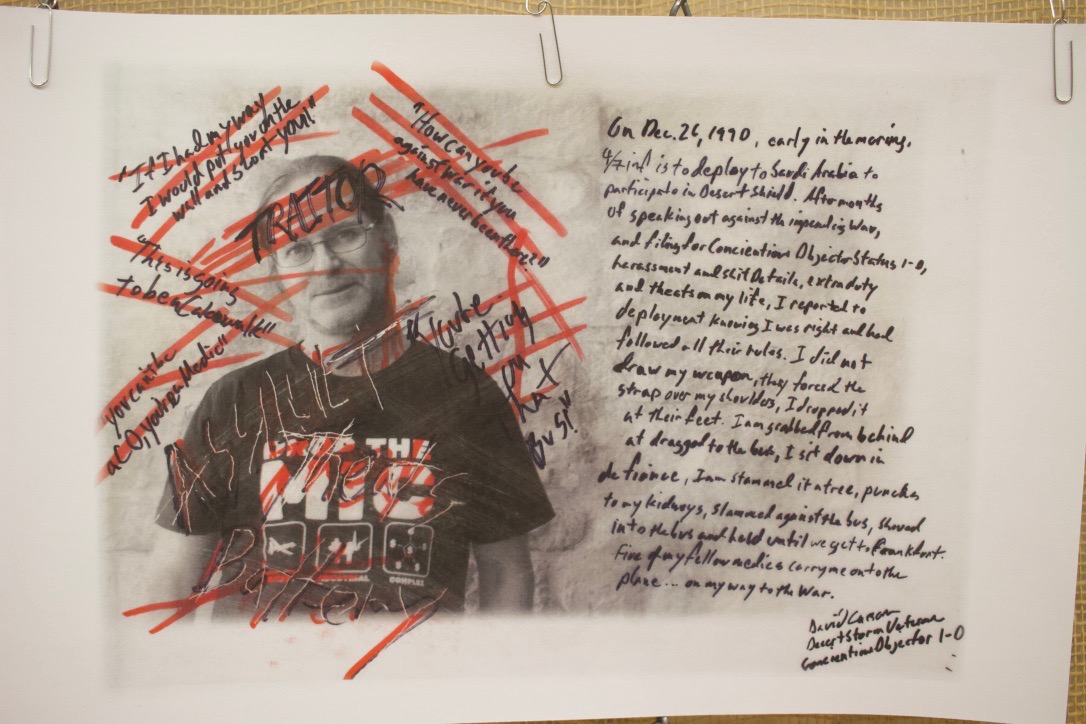

The show also featured several pieces by local veterans in collaboration with Trish Brownlee, a visual artist now located in Washington State who engages veterans in community art projects. In this case, attendees at the recent national convention of About Face: Veterans Against War worked with Brownlee to create portraits printed on cellophane and then etched.

Mr. de la O’s piece was an altar he’d initially assembled and displayed in his backyard, a collection of objects—a traditional Vietnamese conical hat, a history book, a wooden water buffalo—whose origin point and centerpiece was a carving he’d done years before in the cross section of a tree trunk, almost a dedication waiting for an installation.

Later, I asked about the significance of these altar objects during an interview in the kitchen of his little Eastside house. Each object represented something traumatic, he said, something he couldn’t forget decades later. He recalled the water buffalo in particular: “[The Vietnamese farmers] had buffalos there, the people had buffalos. And they would use them in the rice paddies. And sometimes …the [American] soldiers would shoot the water buffalos for nothing.”

Listen to our conversation at Galería EVA here:

After our interview, Mr. de la O showed me around his back yard, where he’d built a small, thatched-roof structure of the sort he remembered from Vietnam. For awhile he’d used it to house his altar and other memorial objects—until he got his motorcycle, anyway. He showed me some stencil art he’d done on the wooden fence surrounding his yard. I showed him a draft copy of the chapbook of poems I’d written based on interviews with Mission Trails residents.

As I was leaving, he mentioned once more that he’d been on hospice at one point, shortly after moving into his house, after his year of homelessness.

“But they kicked me off,” he reminded me. “They said I wasn’t dying fast enough!”

It’s humorous enough to be worth a second mention, for him and for me, because it says something about the day-by-day tenacity that, in my book at least, makes Mr. de la O Decelerator of the Year (if not the Decade: Decelerator of this Decade of Downtown). But it also says something about the slowness and smallness of the scale of our survival sometimes, the victory that resides in that slowness and smallness. Mr. de la O is just one viejito in fragile health living in a small corner house on the Eastside of San Antonio. Seeing him in his flannel shirt, would you imagine he had survived not only Vietnam, but the mass displacement of Mission Trails, a year of homelessness at 70 years old, and finally hospice care for a chronic lung condition? This kind of survival has a depth better captured by Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor’s concept of survivance: the acts of creativity and presence that for Native peoples represent “a renunciation of dominance, tragedy, and victimry” in the face of colonial wars and colonial development projects.

I think of my own slowness: how long it took to write this post, intended as a timely report back on the Veterans Resistance Art Gallery, and the colds and fevers and flus and teething and nursing and birthday parties and school nights and holidays that made timeliness impossible—that made it impossible, most days this past month, to even crack my laptop, let alone have two hands free for typing. I think of the veteran artist whose schedule I couldn’t coordinate with for an interview because she is a single mama of five squeezing art on top of full time work on top of parenting. I think, with gratitude, of the grace and generosity that made it possible to retreat for just a few hours a week so that I could edit the interview above and finish this post. In the slowness and smallness of our survival lies the victory of muddling through, as Kevin Anderson—philosopher, geographer, compost theorist—once described it years ago. “Not enough credit is given simply to muddling through,” his older and wiser and/or more cynical 43-year-old self told me, then an agitated, idealistic 26-year-old grad student tilting at the world-historical. Or as Pavement exhorts, type slowly. At 40, feel like I finally understand the practical and political necessity of all these gentle admonishments.

Poco a poco, we persist—sometimes heroically, sometimes just muddling through.

-30-

Like What You’re Seeing? Become a patron for as little as $1 per month. Sign up for our newsletter (for nothing!). Subscribe to our podcast at iTunes or Sticher. Share this story with others. Or just hang out. It’s always good to kick it together.

Like What You’re Seeing? Become a patron for as little as $1 per month. Sign up for our newsletter (for nothing!). Subscribe to our podcast at iTunes or Sticher. Share this story with others. Or just hang out. It’s always good to kick it together.