In memory of my American Foxhound buddy Parabolic, who died in the heat amid toxic fireworks smoke in July 2023.

Rachel Cywinski

Dying from persistent exposure to climatic heat is not always an obvious and dramatic event. As a Texan now in my 60s who has lived in her own house with little—and sometimes no—air conditioning for 23 years, I sense that some who are habituated to not cooling off for days at a time may simply slip away.

So far as I know, dying of heat is not like reports from people who have been lured into a comforting sleep state during near-death hypothermia. In extended periods of extreme heat such as we have experienced during our recent summers, the body slows down in ways more hidden—but often more distressing—than in the deaths from extreme cold we saw during the rolling blackouts of Winter Storm Uri.

I come to experience this as someone who has lived with multiple permanent injuries due to a 1997 motor vehicle collision. Because of this, getting physical rest already means two to three hours of my knees, neck, and back prompting me to move every few minutes, until my vertebrae have achieved enough space between them to allow me to finally sleep.

Heat exhaustion magnifies and entangles with these and other lived impacts of disability, poverty, and a very limited home electrical supply.

I already move slowly because of disability, but I also move even more slowly because circumstances have not allowed the necessary adaptations and repairs I planned to make when purchasing a house in Highland Park, the original streetcar suburb of San Antonio. With rising heat, these circumstances have come to feel deadly.

The houses here were built without insulation in exterior walls, with fireplaces for the few cold nights and screened sleeping porches to see families through the hottest weeks of summer when even a wall was too much of a heat trap.

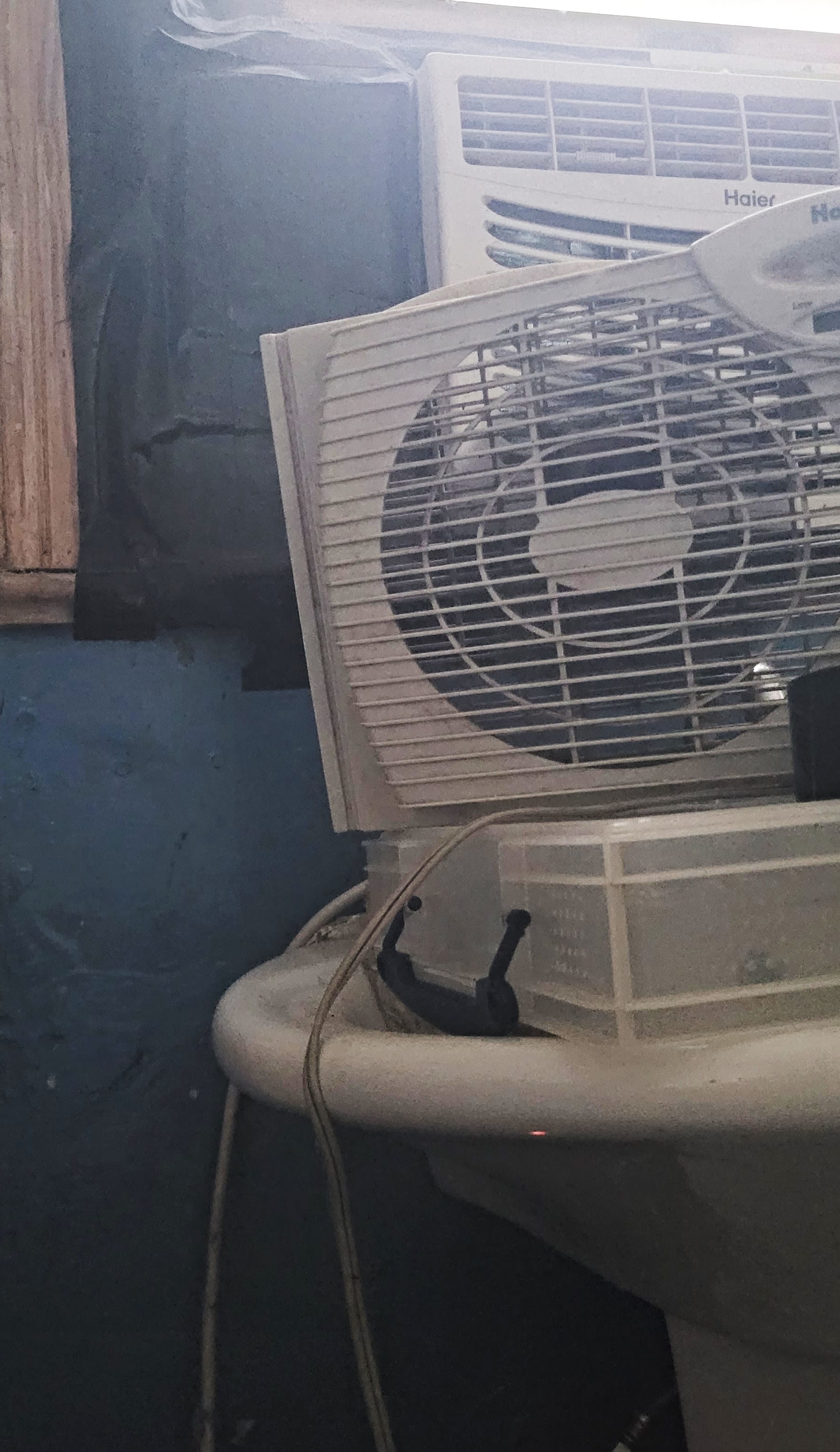

Air conditioning in a house designed without it can also be a trap. Window units prevent windows from being opened for a breeze.

With a four-lane road where the streetcar route once was, an open window at my house would draw in the breezes but also subtropical humidity, gasoline fumes, and raucous noises from poorly maintained vehicles.

I bought this house after a two-year search. Top criteria included access to a wheelchair-accessible bus route, hardwood floors, space for dogs to run, and land to garden.

The first few years I lived here, I would spray water onto the roof at day’s end to lower the heat inside the house. Even now, as a water conservation-conscious Texan, I cringe but still turn on the outdoor faucet, as I know pouring water directly over my senior dogs and myself may be the difference between life and death. Yet the tap water temperature, like the heat in the house, accumulates over many days. The incoming water temperature measurement on the San Antonio Water System meter in my yard on August 21 was 91.6°F.

I bought this house planning to replace the 100-year-old electrical system and insulate it. But poverty and the lack of qualified tradespeople willing to work in older residential communities have made this impossible and required a change in plans.

When a window unit burned out and there was no home delivery during COVID-19 restrictions, I bought a replacement rated to cool 100 square feet and installed it in the bathroom window myself. Since then, any indoor sleeping has been in the hallway outside the bathroom, with the dogs sometimes alternating sleep time on the bathroom tile.

Evening temps have been rising faster than our daytime temps across Texas, though, complicating our survival strategy. And rising humidity is making the heat more deadly.

Last year the dogs decided it was just too hot for them to go inside the house for several months. Each time I had to go to the bathroom, I prayed not to get so tired as to lie down in the house. But this cognitive determination fades when the body is trying to cool down. Many nights I would lie down for a few moments, repeatedly wake up drenched until I had nothing left to sweat, then after several hours wake up for a longer moment and know I needed to get out of the house. I became frightened of going into the house to use the restroom and tried to rush through the house, only to feel even more exhausted.

This summer the dogs and I have longed to lie on our cooler cotton mattresses and cotton blankets, which are indoors. But we can only stay cool enough, protecting our minds from the heat, by sleeping outdoors on the sleeping porch—except during storms.

On August 27 there was a quick downpour, enough to fill the rain barrels. With rain draining the heat off the roof, we were all able to sleep in the hallway on our cotton beds. The dogs drank from their water bowls and were able to rest with me.

There is less daylight every day.

Eventually days will be cooler.

I can’t bear to think beyond that.

-30-

Community Voices provides detailed report backs and opinion from people at the frontlines of community work at the intersection of environment and justice.