On a typical sunny South Texas day, I made a run to the grocery store, H-E-B, near my apartment in Brownsville, Texas. I walked around, and just as I stretched my arm to grab some sausage from the freezer everything went pitch black in front of my eyes.

“Did I die?” I thought. “Is this the afterlife?” When I heard cries from other shoppers and the lights switched on, I saw people’s concerned faces.

This was far from my first power outage in Brownsville, one of many communities stretched across the Rio Grande Valley, which itself spans four counties along the Rio Grande River and the Gulf of Mexico.

Our combined population of about 1.43 million is often referred to by the Wall Street Journal as one of the poorest regions in the country. Brownsville was recently ranked the second “neediest” city in the U.S. Tax dollars don’t reliably trickle back to build basic infrastructure. Instead: We get billion-dollar border walls.

Power goes out with gusts of wind, a storm, or high consumption during extreme temperatures.

Water service is even worse. It’s not uncommon for homes or businesses in Brownsville and throughout South Texas to lose power or face other infrastructure issues, such as water shortages and boil-water advisories. In some parts, people lack access to running water or electricity entirely.

The Brownsville area suffers from crumbling infrastructure due to inadequate funding, mishandling of city resources, and various forms of exploitation. The makeup of this South Texas region is predominantly brown, Indigenous, or Latine. Poverty is an epidemic.

As a local economist summarized recently:

“42.2 percent of children in McAllen … and 39.2 percent in Brownsville-Harlingen live below the poverty line, and many of them live in a chronic state of food, health, and housing insecurity.”

Climate change impacts, such as flooding and extreme heat, make it worse.

Texas has had a record number of state-declared disasters and is gaining a national reputation for frequent disaster declarations, such as those from the Texas Winter Storm of 2022 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

Cameron County Emergency Management’s website says that between 1953 and 2024 Texas has suffered 374 disaster declarations; that’s almost 6 disasters a year. The number of disasters and their extremity due to climate change are increasing, as we’ve witnessed in just the last three years, Winter Storm Uri and the devastating flood that dropped over 20 inches of rain in the Rio Grande Valley last year. These rising crises have forced families and organizations to devise their own solutions for daily survival, and also during extreme weather.

I’m from the Rio Grande Valley and have lived here for several decades, and I have experienced six devastating tropical storms. My late grandma, who was multigenerational from the Rio Grande Valley, taught me to help your neighbor. She met a man from Mexico walking the streets of Mercedes, Texas, who needed a dollar, and she brought him to her house for dinner and a safe place to sleep.

A person helping another is essential; however, a group of us realized that as disasters were rising, different resources were needed. I became a founding member of the South Texas Environmental Justice Network, which focuses on ways to contact those most impacted by disasters and to create ways for immediate aid.

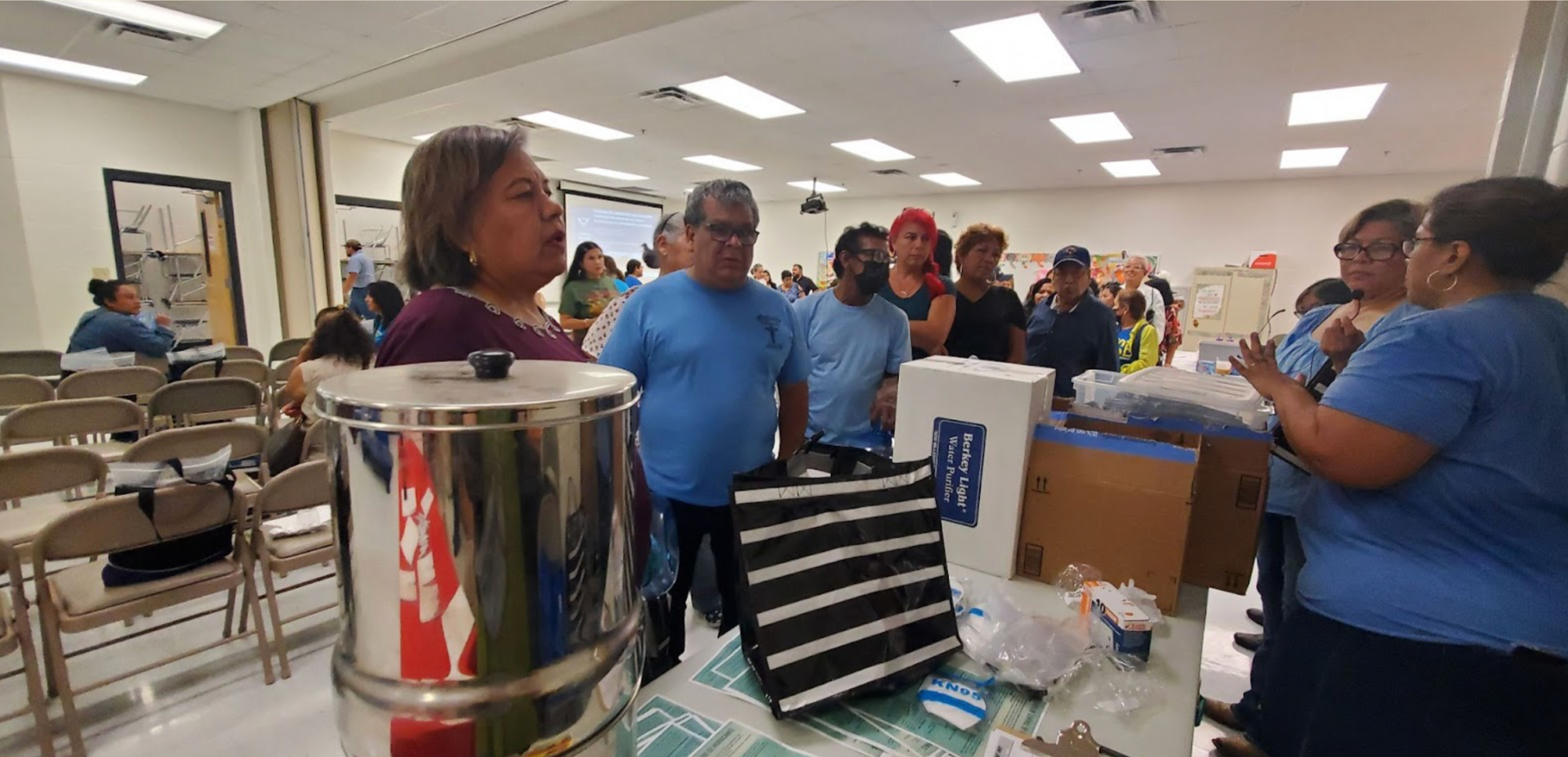

One of the projects that we have developed is a Just Recovery Kit. We built these kits for our neighbors with climate crises in mind, but found many needed them for daily survival.

Each kit may include a high-quality water filtration system, large jugs, a carbon monoxide detector, non-toxic insect spray, a solar battery charging system, gloves, personal protective equipment (PPE), and more. The Just Recovery Kits designed by our members are assembled for each family based on their needs and include contact information should they require maintenance.

Bryan Parras, an environmental justice advocate based in Houston with Another Gulf Is Possible is the lead designer of the kits. He told me how quickening hurricane disasters on the upper Texas coast inspired him.

“It would be in Texas and then Louisiana, starting with Katrina, then Rita, then Ike, Gustav,” Parras said. “It could go on and on.”

Like Bryan, I’ve also experienced an increase in disasters on the lower coast. The area has mandatory cooling shelters for the high temperatures, but never enough. Last year, a family was found dead in their home in Brownsville due to extreme heat and lack of air conditioning. Ask anyone in the region, and they have a personal disaster survival story about living in South Texas.

My colleague’s car filled with water during a thunderstorm; my father was rescued as his car was being washed away.

My apartment was without electricity for three days during Texas’ winter storm Uri.

One summer, my cheap shoes fell apart because of the hot asphalt.

These disasters have severe consequences in a region doubly marked by the daily disaster of poverty. Not only are basic needs lacking, but it can be challenging to find items needed to prepare for or recover from a disaster.

Bryan explained to me how, over the years, the Just Recovery Kits evolved from a disaster kit to one that improves people’s daily needs.

“A lot of our communities are starting in a place where they are behind most of the population; it’s much harder for them to recover from disasters,” he said.

“But if we have products to help them inch their way up to a more equitable space, then that’s the whole point of the kits—to improve their quality of life, their health, their capacity for thinking about emergencies, and to provide them with those things that are unaffordable or not a priority: ‘I have to buy groceries before masks, sorry.”

Dina Nuñez, a community organizer in Brownsville has been forced to rely on the kits daily. She said she doesn’t trust the water coming out of the faucet from the Brownsville Public Utilities Board (or BPUB). Water here mostly meets federal drinking-water standards, but there are ongoing debates over safety still. The Environmental Working Group lists a variety of contaminants found in the water that are known cancer causers.

“I use it [the kit] frequently, especially the water filter, I use it every day,” she told me in Spanish. “We know the water is contaminated, for sure. There was actually an agency that came to my house to do water testing. They tested the faucet, our water mill, and it came back that the city water is actually highly contaminated.”

She went on to say that rising extreme heat means the public utility, which is already failing her with bad water, is also continuously raising the cost of electricity.

“They [the public utility] still don’t want to be responsible,” she said.

“It’s like they don’t actually filter the water. And there are high bill costs coming up. During high heat times, the [kilowatt] usage charge goes up whether we use it or not—BPUB keeps raising those in our monthly electricity bills.”

South TX EJ Network has distributed 200 kits to families living in Cameron and Hidalgo counties over the last three years. Our organization also plans to build a network, or “resilience hub,” of families with kits who can receive and disseminate vital emergency information and help others in their neighborhoods.

There’s a need to inform the public utility of ways to meet the community’s needs. Until improvements are made, the South TX EJ Network will continue brainstorming solutions, such as providing kits to support the families who need them.