In southern drawl and with a grin as big as Texas, ginger-haired filmmaker Ben Masters says, “Oh my God, there’s something you have to see. We got it. We got the ocelot kittens!” Overwhelmed with emotion, he falls gently backward on the thornscrub forest floor, wiping tears. Masters had captured the first-known video of ocelot kittens for a PBS documentary using a trail camera placed near mama’s den.

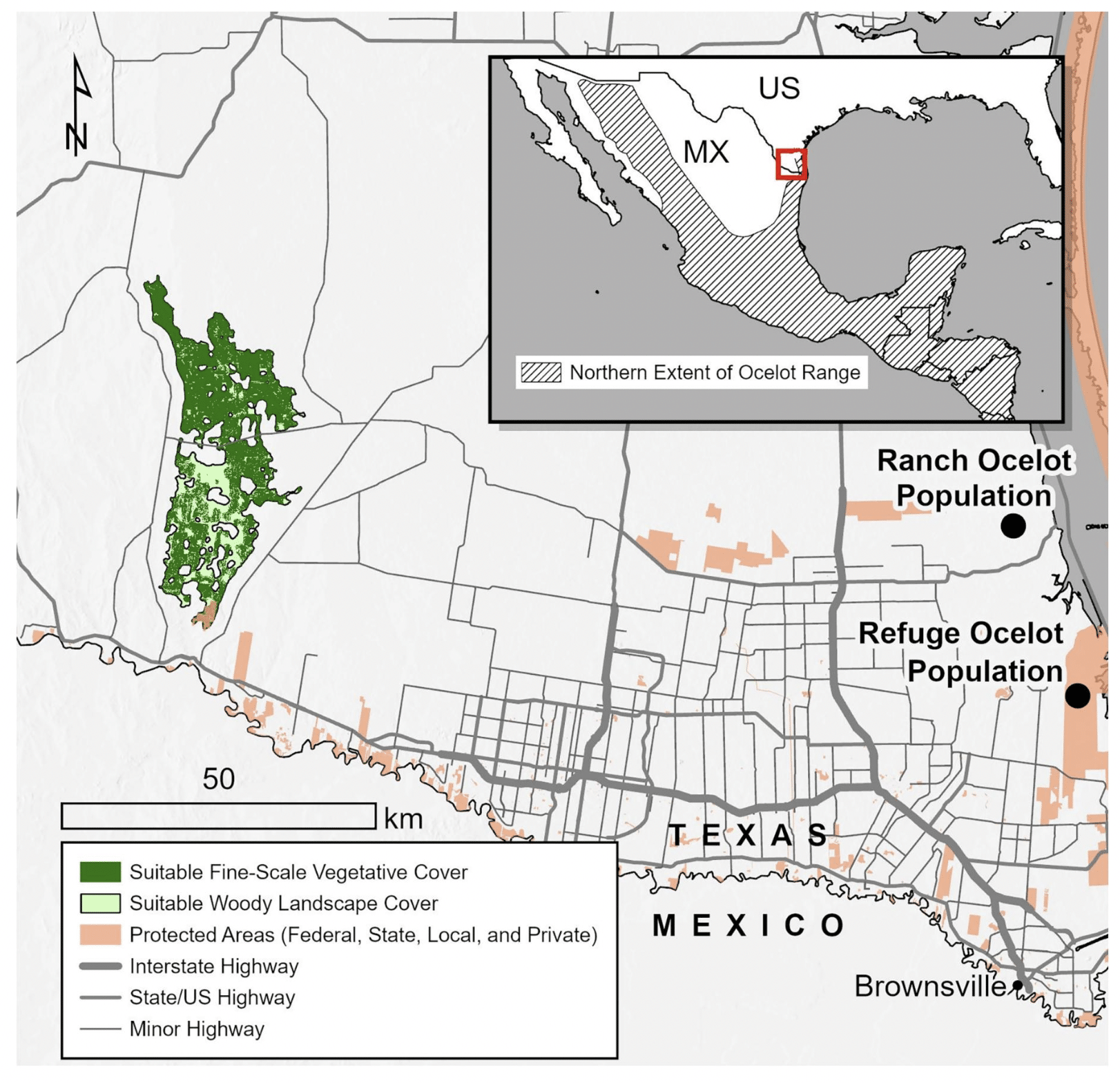

Twice the size of a housecat, the ocelot’s tawny fur spotted with black-lined rosettes that camouflage them in thick underbrush, ocelots live secretive lives, rarely seen by humans. Although ocelots range from northern Argentina through South and Central America to the carrot tip of South Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, they’re endangered in both the U.S. and Mexico. Just 50 to 100 wild ocelots remain in the U.S. in two isolated breeding populations, one in and around Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) in Cameron County and another on private ranchlands northwest of the refuge.

As the crow flies—or the ocelot roams—the refuge lies just 12 miles from the SpaceX launch facility, Starbase. With so few animals alive, a catastrophic event could destroy an entire sub-population.

Connecting and Restoring Thornscrub

The lower Rio Grande Valley is a river delta, a fertile floodplain. Floodplains are known for high biodiversity and this one is no exception, providing habitat for charismatic mammals such as javelina, ringtail, and river otter. It’s one of the “birdiest” places in the United States, with nearly 500 avian species including endangered Aplomado falcons and piping plovers. But the land’s fertility is the ocelot’s Achilles heel. In south Texas, ocelots live only in the slow-growing thicket of thorny shrubs and cactus known as Tamaulipan thornscrub, more than 90 percent of which has been converted to ranchlands, agricultural fields, or towns, dissected by roads (cars cause at least 40 percent of ocelot deaths).

“A lot of ideal ocelot habitat in Texas was cleared, so they are making due with what is left,” says Mitch Sternberg, South Texas Gulf Coast Zone Biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS).

The 2016 USFWS Ocelot Recovery Plan, developed with stakeholder input, calls for protecting “a bi-national corridor of habitat to connect the Cameron County ocelot population to the northernmost known ocelot population in Tamaulipas,” Mexico, some 125 miles south.

Since the 1950s, Texas Parks & Wildlife Department (TPWD) and USFWS have restored more than 18,000 acres of thornscrub in the valley, mostly on public lands, in an attempt to expand available habitat and create corridors. “We have small, bottlenecked populations. Their genetics are really in a bad state, so we need to get acres on the ground—and quick,” says Sternberg, who led the Ocelot Recovery Team until 2021.

In small, isolated populations, animals may breed with close relatives, and the lack of genetic diversity can cause deformities, disease susceptibility, and reduced fertility.

If ocelots could move between Texas and Mexico using this Coastal Corridor, even a small amount of gene flow would make the Texas populations healthier.

Despite decades of thornscrub restoration, the cats’ population has remained stable. “They’ve sort of hit their carrying capacity,” said Christopher Gabler, associate professor of Plant Ecology at the University of Texas-RGV, in a 2022 interview. This means population growth plateaued due to limitations of the environment. “The main thing limiting ocelot populations is the abundance of thorn forest.”

Although thornscrub may not look as majestic as mossy temperate rainforest, it’s equally, if not more, ecologically complex and valuable. And although some scientists have criticized restoration efforts, Gabler and others surmise that the earliest work was not as effective due to a learning curve. “A lot of what’s getting restored are former agricultural fields, so the soil has been enriched with nitrogen, it’s overrun with invasive species, you name it,” said Gabler, who studies wildlife use of restored thornscrub. These thickets need to mature enough to support breeding ocelots.

“The real bang for your buck …is to [replant] right next to where there are ocelots. If …you get rid of invasive grasses and you put thornscrub in there, they’re going to use it because there’s a lot of rodents in there,” added Sternberg. “It’s unfortunate that … stories have said that replanting doesn’t work. They’re wrong. It does work.”

He’s observed ocelots inside replanted corridor patches using radio collars and camera traps, similar to ones Masters used for his documentary work.

Ranchers Protecting Ocelots

The Recovery Plan also includes creating a corridor between the refuge and ranch subpopulations; 50 miles of mostly inhospitable land lies in between—a challenge for even the most intrepid ocelot. Efforts to create contiguous corridors have been limited by land availability, and that’s where private landowners come in. While some groups paint ranchers as being opposed to conservation, with the right coexistence programs in place, ranchers and their lands can be incredibly helpful for wildlife.

The larger Texas ocelot population resides on ranches, including those of the Frank Yturria family and the East Foundation, formed when rancher Robert East died. Since the 1980s, these and other ranchers have worked with Michael Tewes, Regents Professor at Texas A&M-Kingsville’s Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute (CKWRI), on how to support ocelots through land management.

USFWS recently signed a “Safe Harbor Agreement” with the East Foundation so CKWRI scientists can release ocelots onto one of their ranches, which will expand the species’ range northwest. This innovative agreement allows landowners to take in endangered species without consequences if the animals die and protects neighbors not in the agreement.

In October 2024, CKWRI also broke ground on a $20 million, 30,000-acre Ocelot Conservation Facility in Kingsville. They plan to use Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) and captive breeding in an attempt to increase ocelots’ genetic diversity; If you cross a male from the Mexico population with a female Texas ocelot, for example, you’ve accomplished the same goal without creating corridors.

So far, however, efforts at artificial insemination and in vitro fertilization have been unsuccessful, and Texas ocelots have never bred in captivity. Other than competition for limited resources, ART and creating thornscrub corridors can both be helpful tools for ocelot recovery.

Restoring habitat to a state where the ecologically sensitive ocelot can use it takes time, but yields dividends. “These forests are a keystone habitat. They’re extremely diverse. And they’re recognized globally as a conservation hotspot,” said Gabler. “What’s good for ocelots is good for thousands of other species: mammals, birds, insects, reptiles.”

“To people who may not be convinced that thorn forests are important, I point out the ecotourism industry in South Texas is valued between $60 and $300 million a year,” added Gabler. Much of that tourism comes from birdwatching, “a major engine of the economy in the Lower Rio Grande Valley.”

In a devastating report published in Science, the North American bird population has declined by 3 billion since the 1970s, a 30 percent decline.*

Damaging Earth on the Way to Mars?

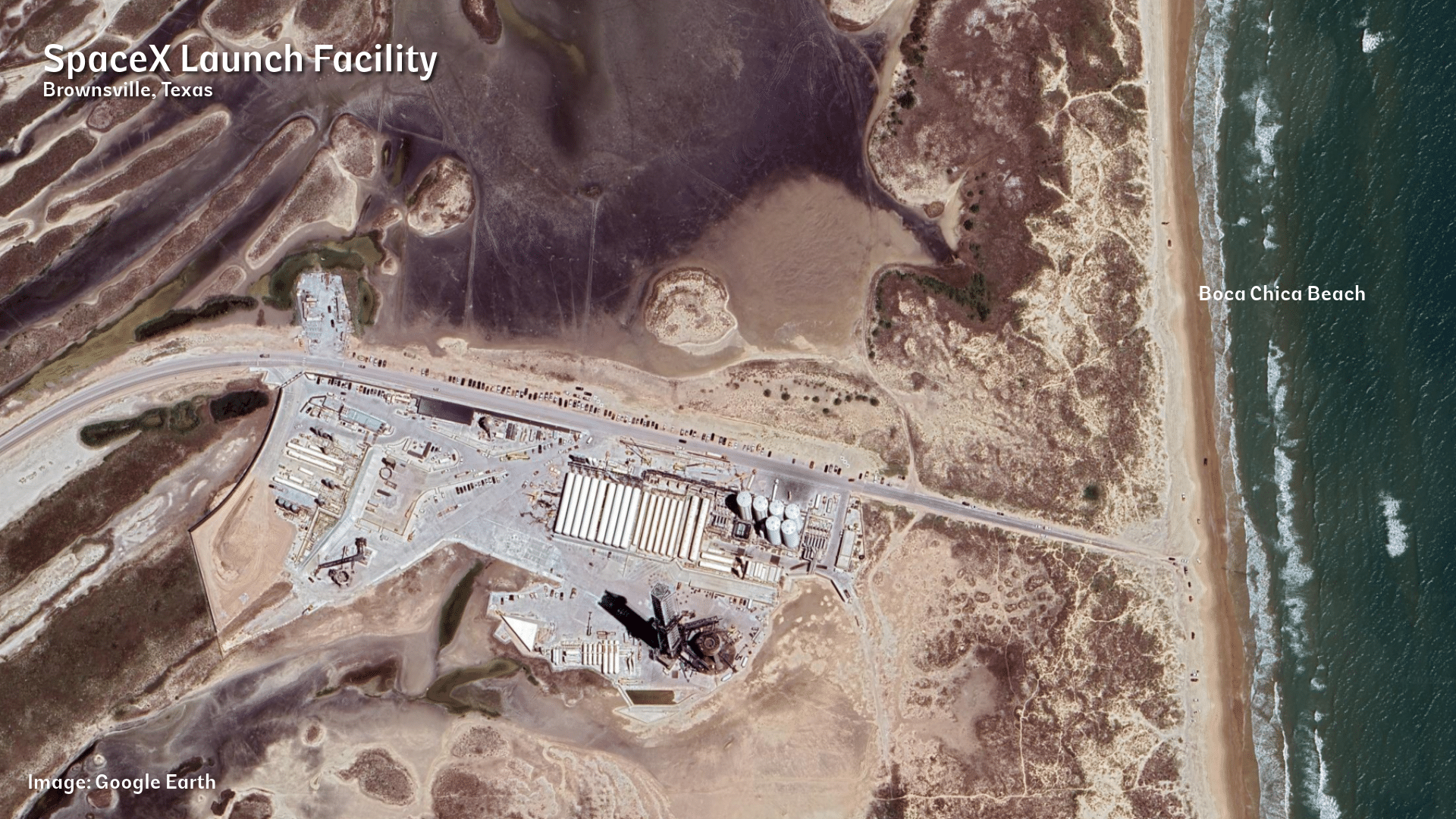

Smack dab in the middle of the planned Coastal Corridor, near the refuge ocelots, SpaceX broke ground on its Starbase facility in 2014. To the untrained human eye, Starbase lies in a vast no-man’s-land surrounded by swirls of sand, mud, and sea—seemingly a great place to launch rockets.

To avian eyes, however, these mudflats appear as a smorgasbord, full of scrumptious treats—clams, crabs, polychaete worms—a crucial restaurant and rest stop for birds migrating north or south.

To the federally endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtles that clamber over mud flats to the dunes, they see it as a place to lay precious eggs away from the high tide mark. The diminutive hatchlings that emerge a couple of months later get blinded and disoriented by SpaceX’s bright lights.

To the ecological visionary, the ones wishing not to damage blue-green marble Earth on the way to Mars, SpaceX presents a blockade in the Coastal Corridor that could connect Texas ocelots to the population in Tamaulipas.

To the Carrizo-Comecrudo Tribe (Estok G’na in their language) native to this region, the mouth of the Rio Grande at Boca Chica is sacred due to its place in their creation story. On holy days, they leave tobacco at the site, giving thanks.

“None of these entities have ever consulted with the leadership of the Carrizo -Comecrudo Tribal nation,” said Dr. Christopher Basaldú, an anthropologist, co-founder of the South Texas Environmental Justice Network, and a member of the Carrizo-Comecrudo Tribe of Texas.

“All of these projects are destroying sacred sites and land against the wishes of the Carrizo people,” said Basaldú. “Therefore … SpaceX and these [liquid natural gas] LNG projects are in violation of the United Nations Universal Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous people.”

At least three LNG projects along the Brownsville Ship Channel adjacent to SpaceX have received operation permits—yet another blockage on the Coastal Corridor. In 2023, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis warned against investing in or insuring these due to the risk of explosions from rocket debris, stating that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) did not evaluate the increased scope of SpaceX in the LNG permitting. Construction on them is, however, underway.

Environmental and social justice groups, including SaveRGV and South Texas Environmental Justice Network, as well as the Carrizo-Comecrudo Tribe, opposed SpaceX and the LNG facilities from the start. “It’s never going to be of any benefit to the people or to the land,” said Basaldú. “But that will always be the propaganda: ‘We’re benefiting your community, we’re bringing jobs, we’re bringing money, we’re bringing economic opportunity’, while people in Brownsville are getting literally priced out of their homes or priced out of their rent.”

A Creeping Scope

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) completed an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) of SpaceX in 2014 based on 12 Falcon rockets launched annually; the EIS requires the company to protect natural and cultural resources—including ocelots, sea turtles, birds, ecosystems, people, historic sites, and public lands—and to mitigate any damage that occurs.

In 2020, in a clear case of scope creep, SpaceX started testing the Starship—the largest, most powerful rocket ever launched from Earth—apparently without FAA approval.

They later received a permit for 5 orbital and 5 suborbital Starship launches a year—on top of Falcon launches. But now, SpaceX wants to launch and land 25 Starships annually, permit pending.

A main focus of Starbase appears to be pushing rockets to their extremes; in other words, blowing shit up. In April 2023, an explosion close to the launch site spewed a rocket’s worth of concrete, metal sheets, and debris through the area and started a wildfire in Boca Chica State Park. It destroyed bird nests on the beach, yellow yolk smeared across the sand.

To prevent that again, SpaceX started using a deluge system that sprays up to 358,000 gallons of water during launches, which they discharge onto the tidal flats. They did this also without a permit, violating the Clean Water Act, though a permit was later granted by Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). If a rocket explodes, deluge water mixes with pulverized rocket components, which includes copper, cyanide, zinc, and chromium, per their TCEQ permit application. Extreme heat from launches can potentially create hexavalent chromium, a toxic, carcinogenic form—made famous by Erin Brockovich. FAA testing indicated its absence after the Starship’s 3rd and 4th launches; neither of those exploded, however.

Musk has also stated that in order to get a million tons of equipment to Mars Base Alpha, they’ll need to launch 1,000 rockets over 20 years, and that planetary alignments favorable to reach the Red Planet occur every 2 years for 30 days. That would require 111 Starships during each launch window, or 3 to 4 per day.

“If the forecast of launch numbers increase like the companies want them to,” says Daniel Walsh, a Ph.D. student at Northumbria University in the UK studying the impacts of SpaceX, “the detrimental impacts that we’re seeing right now are only the start.”

SpaceX did not respond to a request for comment.

On May 3rd, the 500 citizens living closest residents to Starbase (mostly employees) will vote on whether or not to incorporate as a City. Per SpaceX job ads, “SpaceX is committed to developing this town into a 21st-century Spaceport” and “an epic place to live and work.”

Meanwhile, the Texas Legislature is preparing to amend the state Constitution to grant Musk the power to open and close Boca Chica Beach to facilitate more frequent launches—giving away citizen rights to company desires.

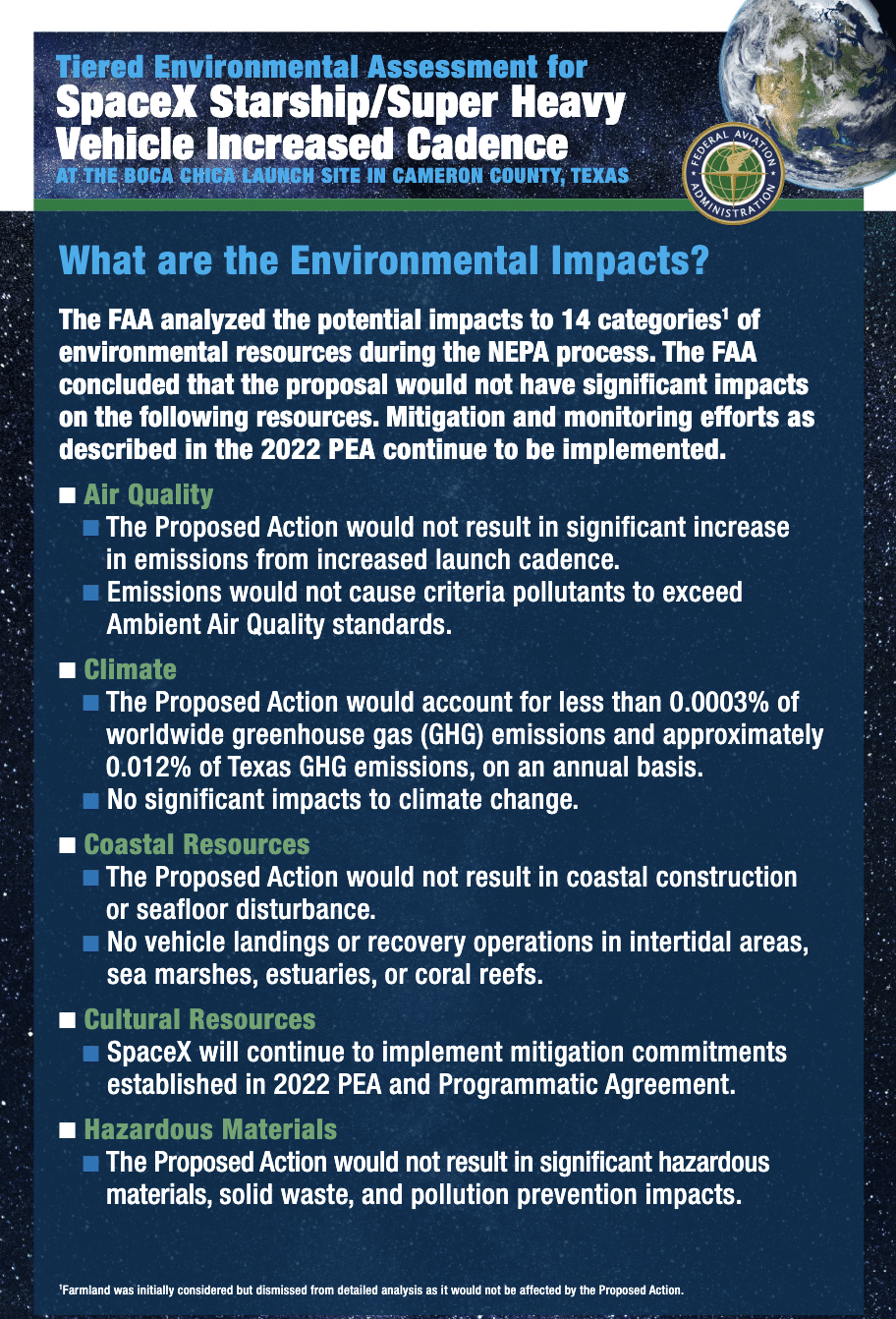

Despite SpaceX’s creeping expansion and desire to launch more and larger rockets, the FAA has not required a new EIS, only a more cursory Environmental Assessment, the draft of which was released in November 2024. In it, they found that there’d be no additional impact to numerous criteria from launching and landing 25 Starships—despite the fact that five of eight have exploded on or shortly after launch, raining down like fireworks across the sky. With regards to ocelots, the EA says SpaceX, “may affect but is not likely to adversely affect/adversely modify critical habitat.”

“That’s just incredible, as in, nobody could possibly believe that. All you have to do is spend two minutes out on the Boca Chica beach area and see that there’s tremendous negative environmental impact,” says Basaldú.

“Imagine that we have both of these LNG facilities operational at full capacity, and a Starship rocket goes up, malfunctions and lands and explodes on a gas export terminal. What’s gonna happen?” And what happens if fiery rocket debris starts a wildfire in the Laguna Atascosa NWR? That population of 20-some cats could vanish in an instant.

In May of 2023, the Carrizo-Comecrudo Tribe along with four environmental justice organizations sued the FAA, demanding they complete a new EIS. That lawsuit is ongoing.

FAA: Findings of ‘No Environmental Impact’ due to SpaceX’s planned increased launch schedule were derided by detractors. Images: FAA slidedeck for recent public meeting.

Modern Day Noah?

In February 2022, Musk told a crowd at Starbase, “We are life’s stewards, life’s guardians. The creatures that we love, they can’t build spaceships, but we can, and we can bring them with us.”

While Musk may fashion himself a modern-day Noah, what could happen if SpaceX contributed some of its billions in revenue toward efforts that genuinely protect the region’s wildlife, ecosystems, and sacred sites? Instead of hastening Earth’s demise on the way to Mars, what if SpaceX acknowledged the impacts their true scope is likely to have over the long-term? What if they truly consulted with and respected local stakeholders’ desires and demands, rather than interrupting long-planned, ongoing ecological restoration efforts, such as, for example, the Coastal Corridor? As the richest person on the planet, Musk can definitely afford to.

“I’ve always been personally interested in sci-fi, that fantasy, that enchantment of it. I get why people might want to go [to Mars],” says Walsh. “But I stand in solidarity with those who are at the wrong end of the hands of power, and space exploration has become this playground for big tech billionaires.”

Humanity often argues over large-scale issues, such as the benefits of NewSpace will bring to a local economy or the harms of gentrifying neighborhoods. Could we consider an ocelot for an ocelot’s sake? Americans spend $137 billion a year on their beloved pets. But the wildcat kitten, out of sight, receives a value of nil.

An Experience Lost

Masters’ footage in American Ocelot captured an experience lost: a human’s ability to truly connect to wild creatures, adored and feared. The thrill of seeing ocelot kittens prancing, which would’ve been rare even when the world was undeveloped, has been replaced by our doom-scrolling cat videos. We see wildlife only in national parks, in documentaries, Reels. Even as we pave their habitat, dissect it with roads, or blow rockets to smithereens all over their homes, they remain out there, clinging to existence, raising kittens, trying to avoid the “screaming owls” barreling down the roadways.

“Our economy doesn’t often take account of different cultures, different ways of being and knowing,” says Walsh. “It feeds on everything until it can drain it.”

Governments sacrifice the sacred to the powerful and money-endowed, while the masses sit by, through their collective silence quietly allowing the destruction of ecosystems, biodiversity, kittens, eggs—the nibbling away of one piece of paradise and another.

For the ocelot’s sake, can we find a way back to the appreciation and valuation of wild things and wild places for their own sake before we truly need a Plan(et) B?

-30-

*Originally reported as three million. Deceleration regrets the error.