“Every sediment sample that we have taken … every single water sample we have taken: every single one has plastics in it.”

—Sandra Metoyer, Environmental Institute of Houston at the University of Houston-Clear Lake

CALHOUN COUNTY, Texas—Since the onset of convenience as commodity, plastic has unequivocally played an integral role in revolutionizing what was possible in the home and at work. Featured on a 1955 cover of LIFE Magazine in a story celebrating “Throwaway Living,” plastic was hailed as the next best thing since sliced bread (which itself rolled out commercially in 1928 to mixed reviews). Only decades after this revolutionary material became synonymous with modernity in its ubiquity are we pulling back the veil on its more sinister natures.

We are are now experiencing and learning the devastating effects of plastic production on our environments, including the results of years of accumulation in our bodies, and the slow and toxic decay of this anchor of disposability into inescapable micro- and nano-plastics (known as MNPs).

In a small community center at the edge of Calhoun County, on Texas’s Gulf Coast halfway between Corpus and Houston, people from across the Gulf South gathered in November for the first People’s Microplastics Conference. Environmental protection organizations, activists, impacted residents, and academics came together to discuss the increasingly alarming effects of the unending accumulation of microplastics now found in “every crevice on Earth.”

Organized by twelve conservation, environmental justice, and Indigenous-based organizations, the conference was the first grassroots convening to discuss the impact of microplastics and efforts to counteract the growing problem of plastic pollution and the interlinked fates of marine and human health.

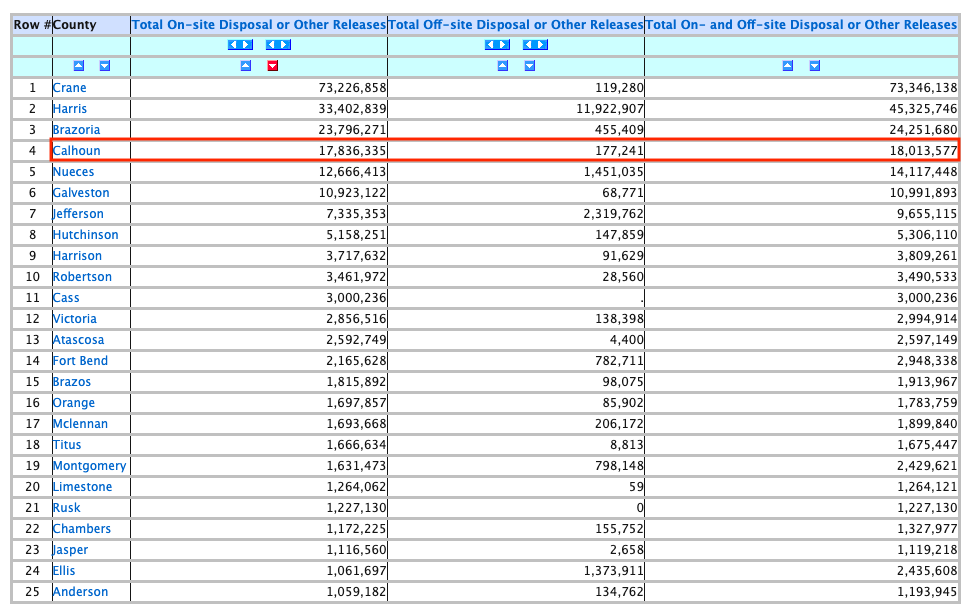

Members of the San Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeeper, a grassroots environmental organization led by globally known activist Diane Wilson, shared how the 1989 listing of Calhoun County as the nation’s top ranked location for toxic disposal sparked an entire movement. Speakers highlighted ongoing research from Texas universities, litigation against the area’s largest plastic and toxic polluters ALCOA and Formosa Plastics, and the decades-long battle to curb pollution of the waterways, bays, and rivers that feed into the Gulf of Mexico.

Calhoun County—which accounted for over half the total toxic waste in Texas discharged in 1989—and the plastic production giant Formosa Plastics operating at Point Comfort became a key focus in the fight to protect lives, livelihoods, and local food sources. By and large, it has been community activists and citizen researchers who have led the fight that has culminated in legal battles and ultimately some wins, including a $50 million settlement that has made much of the current research and continued protections possible, including the Matagorda Bay Mitigation Trust.

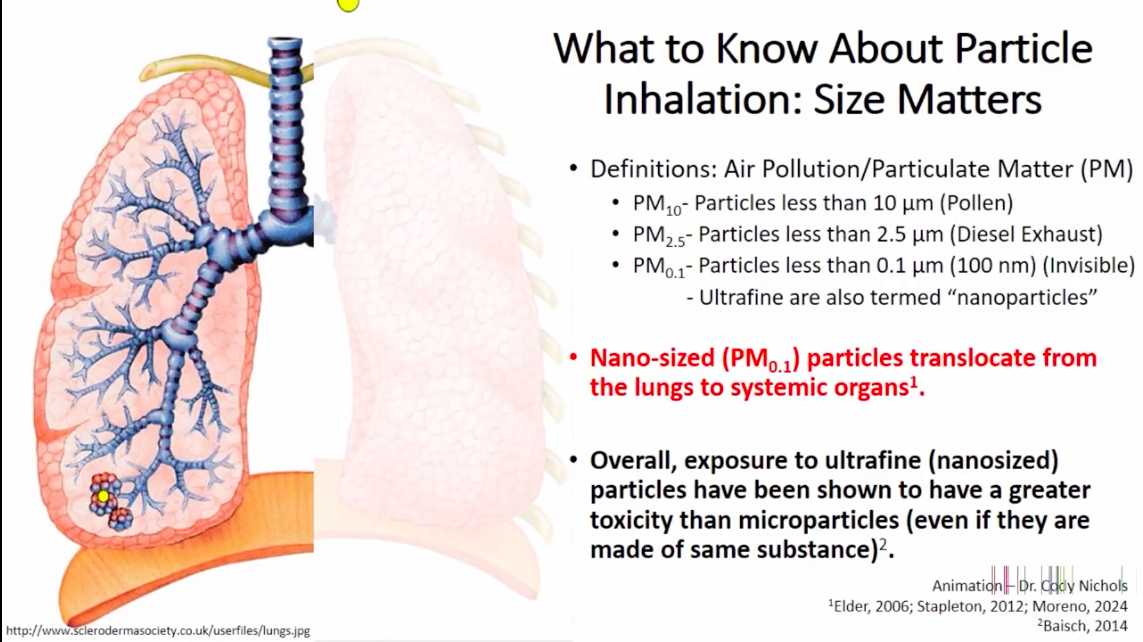

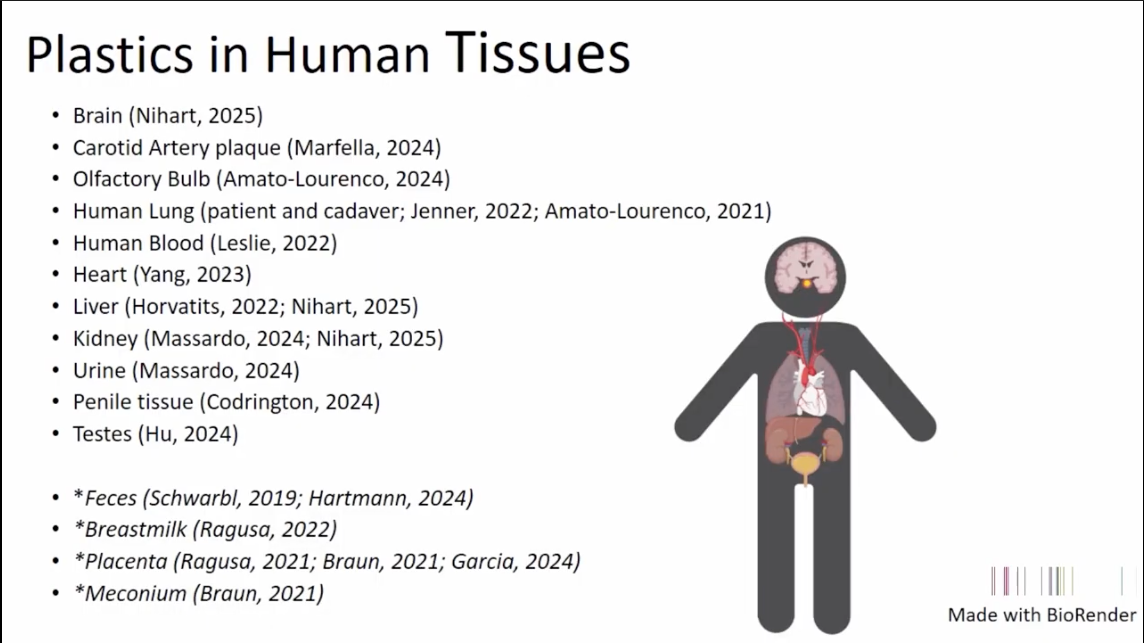

Particle Size Matters (left) and Plastics in Human Tissues (right). Graphic shared at the Microplastics Conference.

But the fight is far from over. Researchers have yet to find any location or creature on Earth that has not been tainted by microplastics, according to Sandra Metoyer, a geographer and executive director of the Environmental Institute of Houston at the University of Houston-Clear Lake.

“What do we know about nano- and micro-plastics in the environment? We know it is ubiquitous, it’s everywhere … the depths of the ocean, Antarctica, the clouds,” Metoyer said.

“Every sediment sample that we have taken with the Environmental Institute of Houston, every single water sample we have taken, every single one has plastics in it.”

Many of the compounds used to produce plastic, known as “forever chemicals” or PFAS, also leech into anything and everything as they degrade.

Research presented at the conference by physiologist and pharmacologist, Phoebe Stapleton of the Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute at Rutgers University, showed that micro- and nano-plastics (MNPs) are able to cross the blood-brain barrier, the last frontier of the human body, making it possible for plastics to enter the human brain. MNPs are also shown to be present and transferable from maternal tissue to fetal tissue during pregnancy, meaning a fetus can inherit the presence of plastic, indicating human contamination in utero. Research on how this affects fetal development, and child development once born, is ongoing.

The known health effects in adults from MNPs, though, are devastating. Research cited by David Halla of the Department of Marine Biology at Texas A&M Galveston, indicates a correlation of dementia diagnosis and higher levels of MNPs in the brain. His own research highlights the presence of MNPs in Matagorda Bay oysters.

Other serious health problems associated with presence of MNPs and PFAs highlighted at the conference include neurological disorders, such as myasthenia gravis, a rare but increasingly common disorder in this Texas county affecting coordination and for which there is no known cure. In fact, one panelist, who still lives near the plant and is diagnosed with this illness, shared her experience with the plethora of health complications that have stemmed from this debilitating condition. She also shared that many of her family members have become ill or died due to illnesses related to toxic exposure.

But the high concentration of nurdles—the small plastic pellets produced by dozens of Texas-based facilities that are the source of much plastic production—is not the only concern for Calhoun County, or the Gulf Coast more broadly. The larger issue is commercial dependency on plastic for everyday products. There is hardly anything in our homes today that does not contain some form of forever chemical or PFAs due to the prevalence of plastic in our daily consumption.

“I look for places where there’s not plastics and I haven’t found it yet,” said Metoyer. “We know that it is in everything. It’s in the oysters, it’s in the placenta, it’s in our brain, it’s in everything. It’s in everything we eat, it’s in what we breathe, it’s in what we wear, it’s in what we sit on. It is everywhere. We know it’s harming the environment. We know it is harming human health.”

With the emergence of increasingly small plastic particulates making it easier to ingest, not only is there bioaccumulation but also intergenerational transferability. The smaller the particulate, the greater the levels of toxicity, Stapleton told attendees.

What’s more, with a market shifting, albeit slowly, away from fossil fuels, oil and gas companies have increasingly shifted to plastic production. These corporations find Texas an attractive location for this shift, due to the readily available resources and existing industry as well as lax environmental protections and enforcement, all of which disproportionately affects racialized communities.

This is where the fight led by community activist and environmental advocate Diane Wilson continues. Wilson has served as a leading voice and muscle in the lawsuits and local battles with law makers, business leaders, and even lifelong neighbors. Her story, and the fight that changed the course of the health and future of Lavaca Bay is narrated in the recently premiered documentary Hellcat, which screened the second day of the conference followed by discussion with Wilson and director Fax Bahr. This documentary vividly and viscerally places a lens on the fight that led to the $50M Clean Water Act settlement against Formosa Plastics, an unprecedented citizen-initiated lawsuit made possible by citizen researchers and former Formosa employees turned whistleblowers.

It is notable that much of the continued research on microplastics in the Bay has been made possible by money won in the settlement. This victory is the lighthouse guiding those fighting for restitution and protection elsewhere. People like Sharon Lavigne, the Founding Director of RISE St. James in St. James Parish, Louisiana, also known as “Cancer Alley,” who has lost several family members to petrochemical-linked cancers. And people like Nancy Bui, a fishing community activist who also led communities of Vietnamese fishers to fight against Formosa in Vietnam.

These three women, Wilson, Lavigne, and Bui, all of whom were present at the conference and spoke vehemently about their fight against megapolluters like Formosa, said they hoped the next generation of activists would be bold fighters, that the conference would be a source of inspiration and community building for the struggle against plastic pollution and, ultimately, usher in the end of the plastics era.