Legal rights for wild nature are increasingly being enshrined in legal systems around the planet. Federal, state, and local governments—oftentimes led by Indigenous nations—are adopting protections for non-human species at a rapid clip. The momentum is such that some are working to ban the practice before legal claims are even made, such as the Republican-dominated Utah State Legislature where the Great Salt Lake is on the verge of ecological collapse. At the 12th World Wilderness Congress last week convened in the Black Hills, Hé Sapa in Lakota, Deceleration sat in on a panel concerning efforts underway to enshrine rights for nature, particularly from an Indigenous perspective. (See: “WILD12: It’s Time to Step Up to Protect the Legal Rights of Nature, Panelists Say.”) We later sat down with Britt Gondolfi, the panel’s moderator, and asked her help to unpack the possibilities of the rights of nature movement. Rights of nature may be a novel concept for many, but it is part of a growing toolbox being accessed to protect the Earth and her many families, who together make humanity’s livelihood on the planet possible. Here Gondolfi, the Rights of Nature Project Coordinator for the nonprofit Bioneers, puts the rights of nature movement in historical perspective by highlighting past legal supports for such odious practices as human slavery and denying women the right to vote. She also offers a shout out to San Antonio organizing efforts to protect migratory bird rookeries from the City of San Antonio’s violent displacement efforts across the parks system. As she concludes: “Save Brackenridge Park!” — Greg Harman

Britt Gondolfi, 12th World Wilderness Congress

Recorded August 30, 2024

Britt Gondolfi: So I never expected this to be my path. I was originally working with a group of high school students, with an extracurricular program. We created a fake newspaper. Before fake news was fake news, we were we were making fake news from a future that we would want to see. So we were writing utopian news stories, a nd our high school was approached by Bioneers to participate in a intercultural youth program.

Greg Harman: This is a high school in Louisiana?

In Atlanta. I was in Atlanta at the time. And so I was the chaperone. So that’s how I came across Bioneers. And I was raised in the deep south. So when I went to this Bioneers conference, I was like, oh, this is like church camp, but this is for the planet. And this is a church camp that I can definitely get behind in my adult life. And so from chaperoning youth to come to the conference, I eventually was inspired to go to law school. And while I was in law school, I was approached again by Bioneers asking if I could assist in doing research on the question what would happen if, tribes that have federal recognition in the United States passed rights of nature laws—or laws that acknowledge the ability of nature to be protected and spoken for in tribal court systems.

And so I started doing research and helped do a lot of the educational materials that they created. And one of my biggest takeaways from that research was in addition to the work we have to do in getting nature’s, you know, cries and pain heard in our court system and using our court system as an instrument of justice and as a vehicle to protect our planet and ecosystems, we also have to fight like hell for sovereignty to be reinstated. I’d never realized, how…I mean, of course, we all realize the effects of settler co colonization. You have to live under a rock to not. But I didn’t realize things like tribes didn’t have jurisdiction over a non Indian or tribes’ jurisdiction over incidences that happened in the reservation on privately owned land, or what they call fee land, was limited. Right.

I didn’t realize that the Supreme Court had limited tribes’ ability to file lawsuits against non Indians. Just absurd things that I think the general public is ignorant of because it’s outside of our daily lived experience. Like, I’m a descendant. I wasn’t raised in a tribe. I wasn’t raised in any culture. My father’s grandmother was taken to a boarding school and that was kind of the severance of that community and my family. You know, so coming into this work is is an honor and it’s something that I do in honor of my grandmother and her sisters’ experience and what they survived. But I had no idea. I was like, wow, I’m so ignorant about these things. I know I’m not the only one.

So our work in Bioneers is, you know, we we platform and bring together people that are on the front lines of social justice movements, environmental movements, Indigenous rights, and Land Back movements. But we also, on the side, invest in kind of instigating some movement ourselves. And so bringing this idea of tribes flexing sovereignty with the rights of nature law is something that kind of kept on coming out of our forums and caucuses.

So yesterday on the panel you were facilitating, you kind of defined what Western legal frameworks are based upon. They’re based upon the right of the individual, the individual to control the land. At at what point does even a right of a stream or a fish or a bird enter into kind of, like, Western law, as we’ve experienced it within the last few years?

There’s nothing. I mean, the closest thing that we have to a rights of nature paradigm is a common law concept called the public trust, which basically means that sometimes courts have found for communities screaming stop. Communities go to the courtroom and file an injunction and that’s just…

Based on their own hurt—as people.

Yeah. Like you’re gonna hurt me. Like, this is gonna hurt my health. This is gonna hurt my property value. Or, you know, in in many cases, you know, this is going to hurt an ecosystem which will collectively hurt all of us. But our courts have made it extremely difficult for environmentalists to carry these complaints before a judge because they’ve made up these jurisprudential rules of standing, where whoever is the one that brings the case has to be the one that is either going to suffer the harm or has suffered the harm. And nature is not able to be a plaintiff because our law doesn’t allow for that. So we have to find people that are the victims of ecological disasters to be these plaintiffs. And then sometimes, our courts will say, well, yeah. I hear you. You’re all getting cancer, but we can’t shut this place down. They give so many jobs. It’s in the public interest to keep it there.

Our courts are not perfect vehicles for administering justice. It’s just one of a litany of many environmental strategies that we have to take up.

So Grandma Camp [Casey Camp-Horinek] yesterday was on on the panel describing how the Ponca Nation in Oklahoma have been at the vanguard of asserting rights for wild nature, for rivers, right? And for the lands there. But they’ve made a decision to do that in their tribal courts and not enter it into, to try to try to push it into federal courts that have been so destructive to Indigenous peoples. Can you point to where laws are being applied at a large scale in the federal court system? Is there progress being made? Maybe not in this country, maybe in other countries. Maybe a couple highlights that folks will be able to be like, oh, that’s a cool idea.

Well, I will say that the articulation of the value system that our natural world has a right to exist, persist, and thrive, is something that needs to be articulated even if we know that they’re going to shut it down. And that’s what we see happening across the United States with all the various counties and townships that have passed these rights of nature laws or these environmental, rights acts. You know, it’s the articulation of a moral value system.

So how many? We’re talking about city councils and county governments?

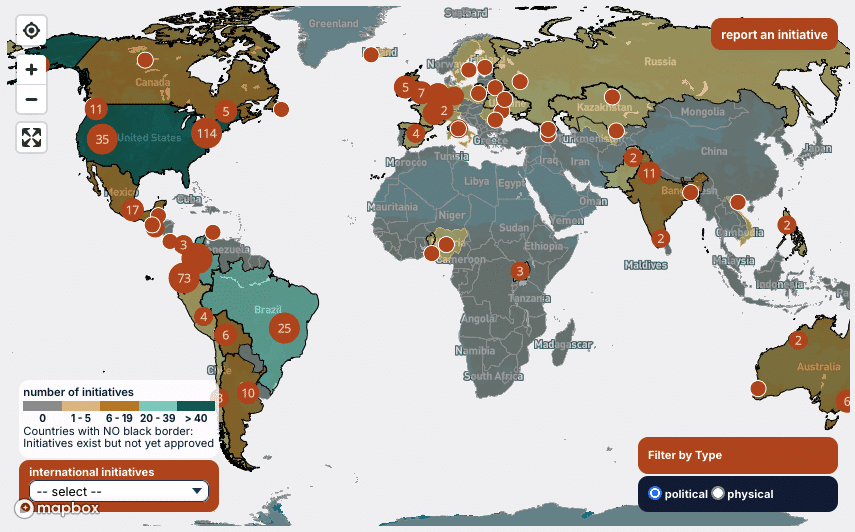

Oh, I mean, like, in the hundreds. Across the United States. There’s a really great website, Eco Jurisprudence Monitor, and you can see how many, non-tribal governmental entities are passing these laws. And how do we know that it’s making an impact? Well, because there are states, like Utah just recently, is trying to ban rights of nature laws. You know? You know you’re on the right path when your enemy comes against you strongly. And so we see that in the Rights of Nature movement. We’ve seen lawyers threatened with sanctions using the Rule 11 and the federal rules of civil procedure. We’ve seen lawyers threatened to be disbarred. We’ve seen a lot of, a chilling effect.

Lawyers coming in that would even assert the right of, let’s say, an egret or a heron, for its own livelihood. So they’re saying, we’re gonna throw you out. We’re gonna take your law license.

Yeah. They’re basically like, it’s a frivolous lawsuit. There’s no grounding law. I mean, we do have things like the Endangered Species Act. But the problem is that if you’re gonna carry out a lawsuit in the name of an endangered species, you’ve gotta wait for that species to be endangered in the first place. Why are we setting up a legal system that calls in the necessity of protection to a point where it’s almost too late? And not only that, not only are we waiting for it to be too late, we’re also requiring people to show some sort of nexus or connection between their self interest and the species. And that’s baloney. We should be able to go to court and litigate to protect ecosystems for the ecosystem itself. Because we need it, and it needs us to be able to speak for it.

So we spoke a little bit yesterday. I think you brought it up. I mentioned where I was from, and you said, oh, the Yanaguana coalition. Can you tell me about what how you understand the local struggle?

Hey, San Antonio. Leave those birds alone. You know?

Yes. Thank you.

I mean, it’s a perfect example of why we need these kinds of laws. Because if we had laws that honored nature’s right to exist and people’s right to protect nature in our court system, the women of the Yanaguana Coalition would have been able to go to court, sue the city of San Antonio in the name of these migratory birds, because this is one of the last few nesting places they have. This is an ancestral home for them to create the next generation. And I don’t care what other trees you go and plant. Once you take those trees down, you are displacing all of these species, and you’re committing ecocide. And I don’t care how much the birds shit in the park. They need a place to shit. And believe it or not, that ground needs that shit. Excuse my French. I’m from Louisiana. We can’t help it. You know? But they need that. This ecosystem needs these birds. Yeah. And for us just to say, well, it’s an inconvenience to the aesthetic is disgusting.

And our children will be disgusted, and our grandchildren will be disgusted. I mean, I’ve heard horrific stories about people going into the park and banging boards and making explosives go off to move these birds.

City contractors. Yeah.

Are we out of our minds? And then we gaslight the women that are standing up. We had that lawsuit where, two Indigenous elders basically said that this is like a sacred prayer site. And you you have your churches and we have this land that we have a connection to. And it it holds a cosmology for us that cannot be replaced. It cannot be replanted or moved somewhere else. There’s a relationship of protection between these people and these birds. And there’s nothing that we can do to replace what will be lost, you know? And so, keep on fighting. City of San Antonio: those birds have a right to be there. And just watch where you step. Be an adult and watch where you step. That’s their home.

So we we heard yesterday that there’s these different areas of earth law, earth jurisprudence, and rights of nature being one. Rights of future generations, or the right to a stable climate, we’ve seen. Healthy environment, right to water. How would you advise a community like that in San Antonio on ways that they could use these evolving areas of law to protect our ecosystems or our sacred places?

Well, so much of the process is about creating a stance and a position. And so I would say to the naysayers, creating a law that acknowledges the rights of these birds, for example, in San Antonio, is the creation of a rallying cry. You know? It shows the sides. It’s gonna show, you know, everyone can pick a side.

Of course, our western legal system will just try to strike it down or invalidate it or gaslight it as being a crazy idea. But you know what else was once a crazy idea? Women voting, not having the right to own another human being. Those were all crazy ideas at a point in our society. And, I mean, who is the crazy one? The person that’s defending the ecosystem or the person that’s justifying the ecocide?

So even if it is just existing as a symbolic law or a declaration of a position, it can become a community organizing tool. And I think what the two Indigenous elders did by using, the Native American Religious Freedom Act is bold and innovative. And I don’t think that there should be a competition amongst the environmental movement lawyers as to which theory works best. We need to try all of them and we need to be relentless because it’s going to take a massive change in public opinion and pressure and massive changing of the guard in our legislative systems at the state and at the local level. I mean and, of course, at the federal level, as well. These these kinds of movements of identifying a new rights bearing entity, it took time. It took time for women to get the right to vote. It took time in a war to abolish slavery.

Heavy agitation.

And so we are legal agitators. But we’re also agitating for a cause.

I love that you’re informed about the struggle of what people and our related species are going through. And I thank you so much for articulating that and for the encouragement.

Yeah. I mean, women are fighting really hard, not just women, but I I know personally some of the women that yeah. They’re at the forefront. They’re being harassed by cops. They’re being harassed by city contractors. And it’s wrong. This is not the way we treat our elders. This is not the way we treat the wisdom keepers and the protectors in our society.

I mean, the city of San Antonio needs to offer an apology to this coalition and to these women for the way that they’ve been treated. And if the citizens of San Antonio realize that this key ecosystem is gonna be a make or break deal for the survival of this species, I think much more people would be rallying around these women. And it’s it’s absurd.

And it’s just a perfect, perfect example where we’re having to have a fight and protest in the streets when what should be happening is we should be able to go before a judge and say, excuse me, your honor. What they’re about to do is going to destroy something that can never come back. It’s gonna cause irreparable harm. There’s imminent danger of us losing a key species and a key ecosystem that this species relies on. And any sound moral judge that had any level of heart would say, you know what? You’re right. We need these trees. I mean, did we not read The Lorax when we were kids? And it’s sad.

It’s sad that we even have to have these legal debates over something so simple as do we want this crane to survive. I mean, what do you want? Do you want the parking lot? Or do or do you want this species to exist?And it’s gross. So I just I wish them the best, and I hope that people go and, you know, go put their bodies out there. Go sit out there. The law will not solve everything. The law is just one tiny tool in our toolbox, one that we have to use, but we have to also use direct action. We have to also get the word out and create press that shines light on these stories. It’s not a this or that. It’s all of it.

Fantastic. Thank you so much for your time. Safe travels when you do go back.

Save Brackenrdge Park.