At the bottom of a flyer for an upcoming panel on the Philippine “Golden Years”—a now-ironic name for the period of martial law enacted by autocrat Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. from 1972-1981—is a line from Czech writer Milan Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting:

The struggle … against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.

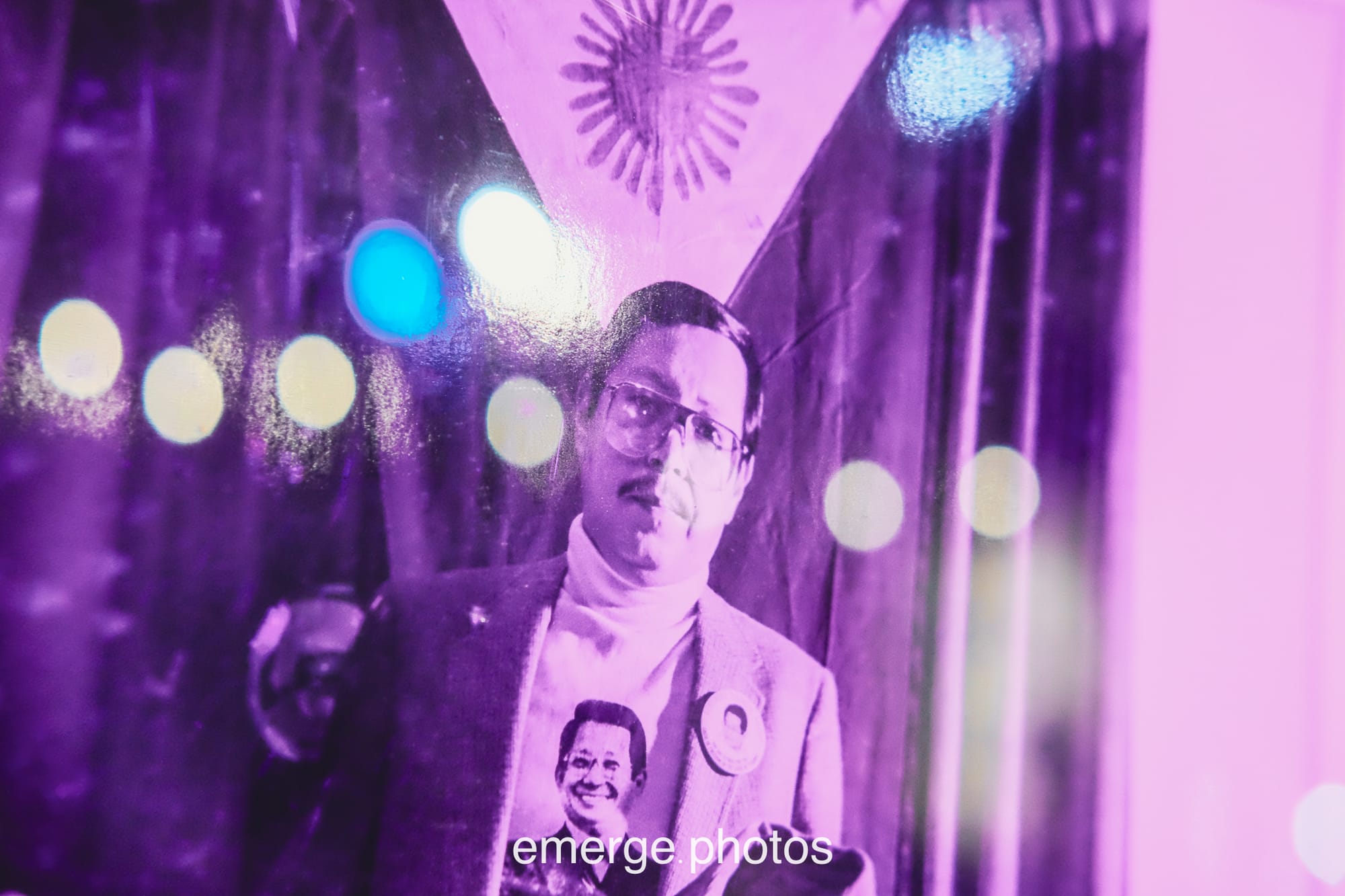

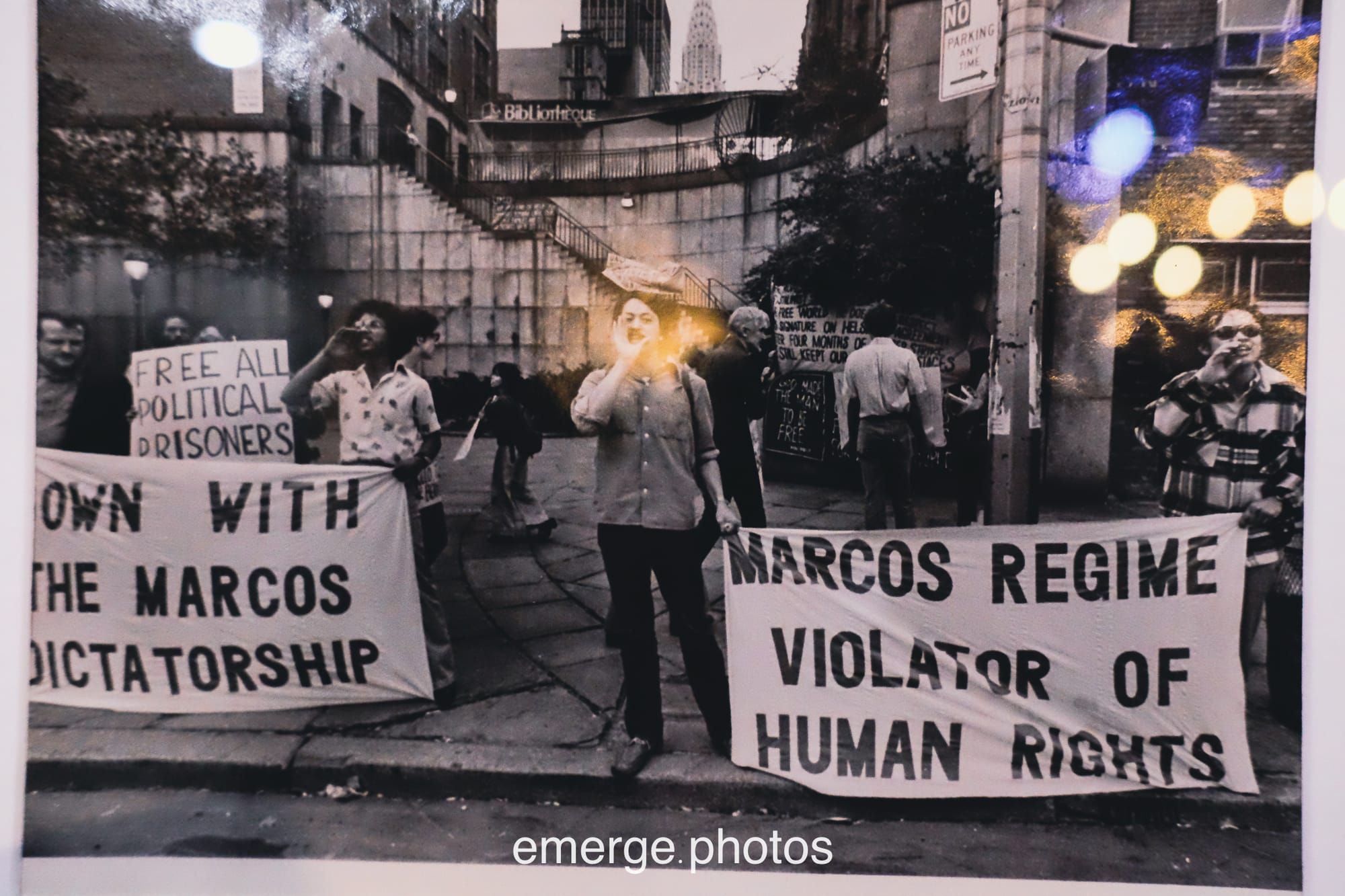

For Myra Dumapias, an organizer with the Filipino American Historical Society of San Antonio and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders for Justice in San Antonio, it’s a quote that captures the power of a traveling exhibit making a stop in San Antonio through December 2025. Curated by Victor Barnuevo Velsaco, “Golden Years” is a collection of photographs originally printed in U.S. news media that captures the rise of Marcos from president to dictator, as well as the people’s movements, opposition candidates, and institutional defections that finally ousted him in 1986.

Originally from the Philippines, Dumapias’s own family migrations—from Manila to China to Malaysia then back to Manila briefly before stays in several other countries—are a product of Marcos’s rule. A professor of political science, Dumapias’s father left academia for the foreign service after learning he’d been placed on a watch list by the Marcos regime, which suspected him of being a faculty advisor to student protestors. He wasn’t, but administrators warned him to tone it down just to be safe. As a political scientist, he’d encouraged critical analysis in his students, fostering debates that included both pro- and anti-Marcos positions.

“He was simply teaching about the signs of what a dictatorship looks like, and it was happening,” Dumapias shared, after speaking with her father to clarify details.

More than fifty years later, he recalled the regret he’d felt in throwing out “valuable books about histories of revolution” that had been important sources for his teaching and research in political science.

Then her father got an anonymous phone call saying Dumapias and her mother were “next” to be kidnapped. It was early into martial law at that point, Dumapias said, but already people were being disappeared.

Knowing those who’d been watchlisted were barred from leaving the country, Dumapias’s father signed up to take the foreign service exam, “because he thought it was the only way he could leave the country with me and my mom,” Dumapias said. Out of more than a thousand applicants, her father was one of just 15 who passed.

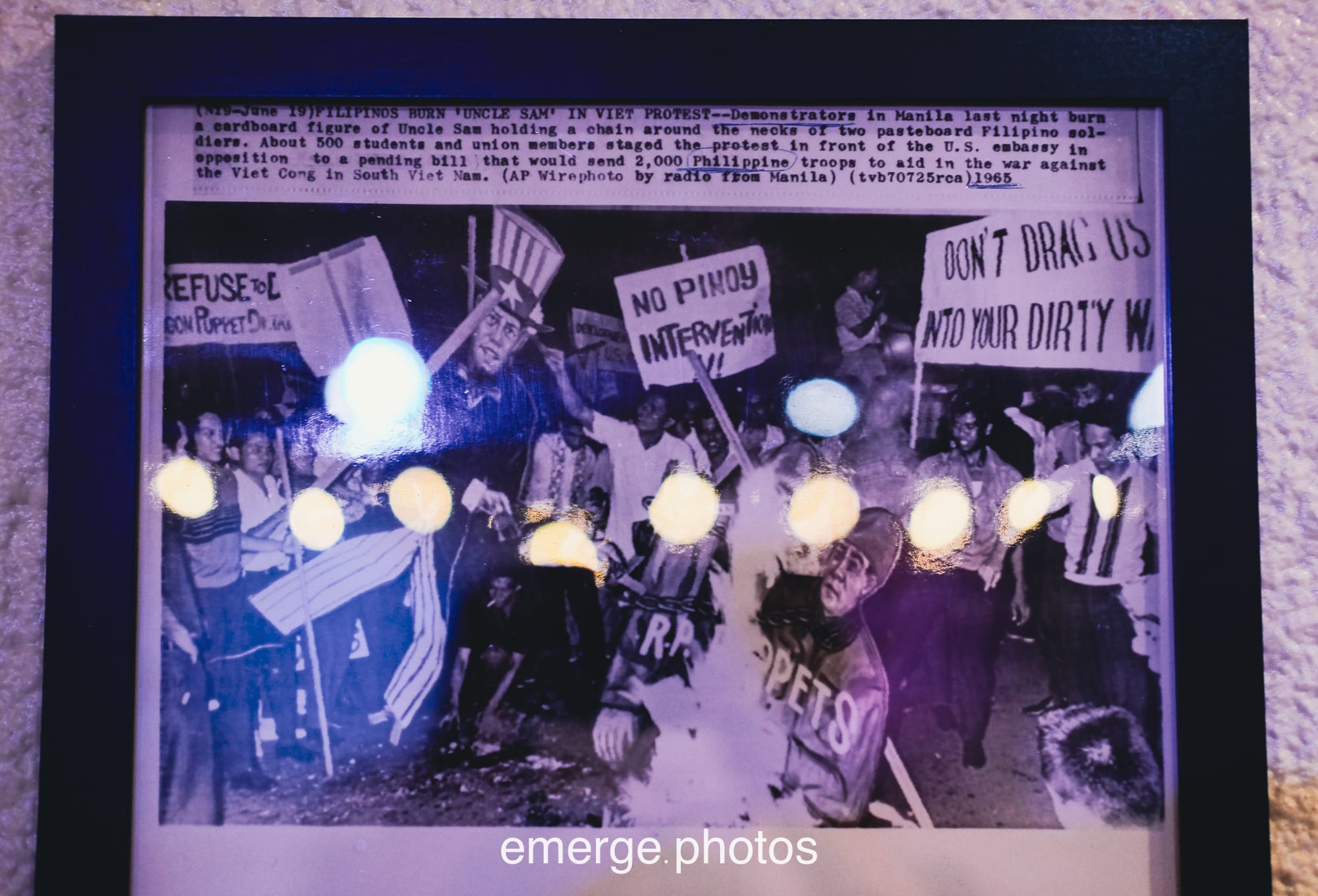

In one photograph from 1971, a student around the same age as those who would have been taught by Dumapias’s father holds a sign that reads: “Marcos – Hitler II.” According to the wall label below the photo, the student protestors “seek the return of habeas corpus”—the right protecting citizens from unlawful seizure or detainment by their government. Marcos had suspended it about a year before imposing martial law in 1972, purporting to “save the republic” from alleged plots against him.

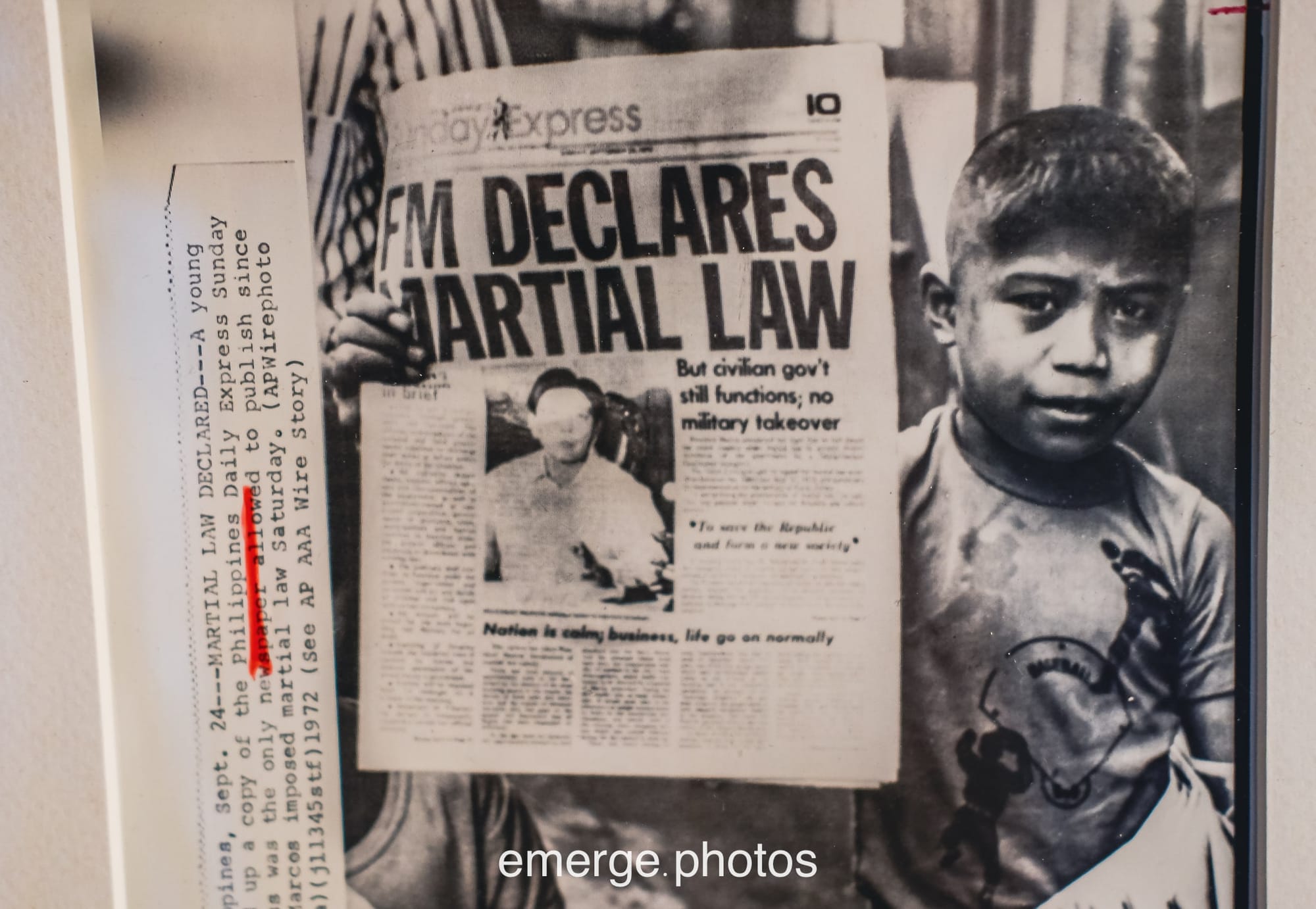

In another photograph commemorating this decree, a boy holds up a copy of the Philippine Daily Express, whose headline reads “FM Declares Martial Law.” “But civilian gov’t still functions,” reads the subhead; “no military takeover.” By that point in Marcos’s rule, states the wall label, it was the only newspaper allowed to publish. A year later, Marcos announced that martial law would continue indefinitely and elections would be suspended.

The “Golden Years” saw 3,257 murdered, 35,000 tortured, and 70,000 illegally detained by the Marcos regime, according to historians based on data assembled by Amnesty International and other human rights organizations.

Marcos and his wife Imelda also presided over the extreme impoverishment of their country, even as they used their office to enrich themselves. In an echo of the images of genocidal mass starvation out of Gaza, one photograph highlighted by Dumapias shows a severely emaciated young girl suffering from extreme malnutrition, “one of many children dying” at a Bacolod hospital in 1985, the label reads.

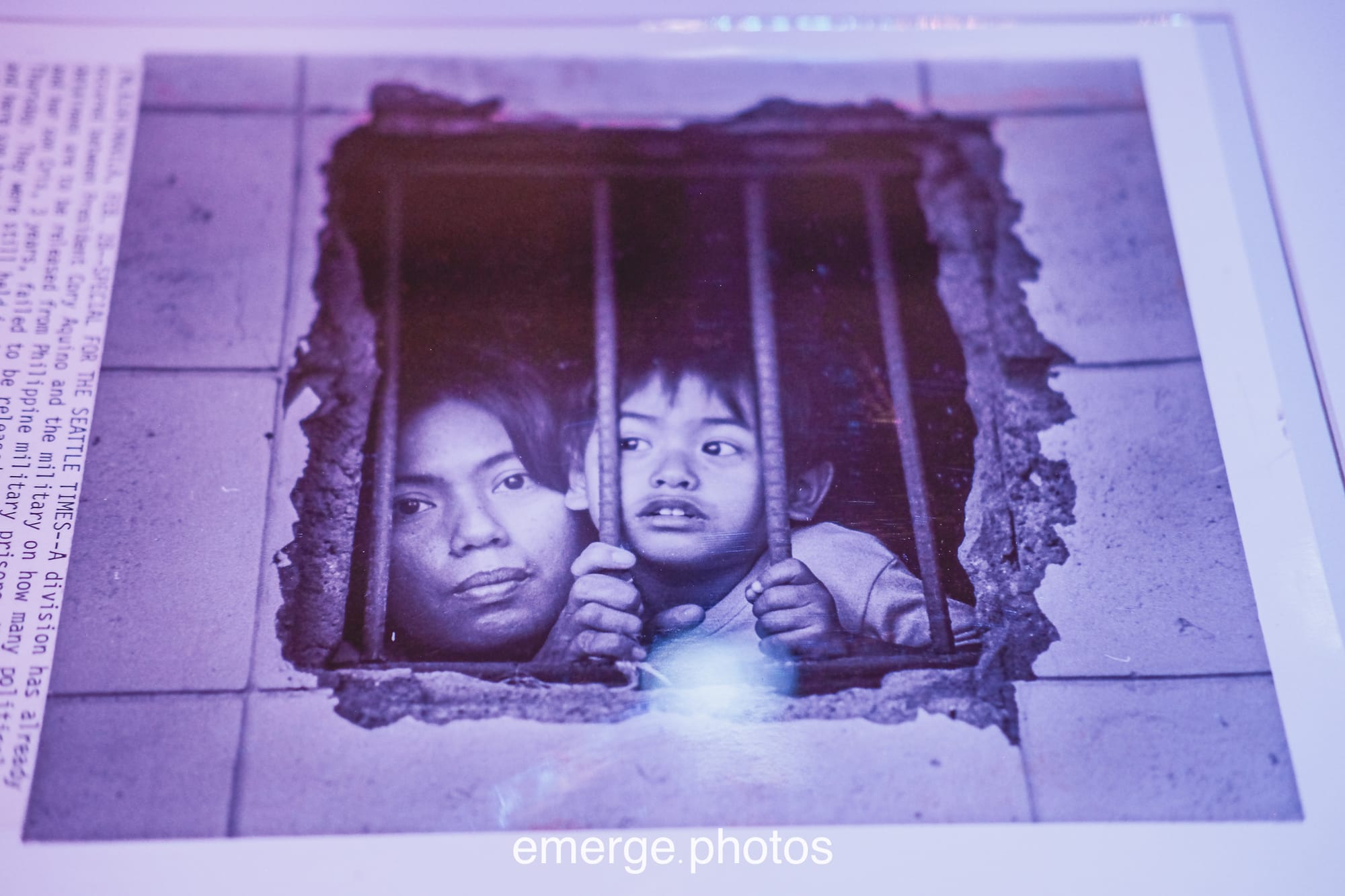

In another, a woman and young boy peer out of a window behind metal bars. The woman was pregnant when she was imprisoned for being a dissident, Dumpaias said; her son was born in prison.

After their migration out of the Philippines, Dumapias’s family returned briefly to Manila for a home-posting in the mid ’80s.

“Toward the end of the Marcos regime,” she recalls. “And I was also there to watch People’s Power spring into action…to take down a dictator.”

Event Info: As part of Filipino American History Month and in recognition of Dia de los Muertos, “Golden Years” Panel: Surviving Martial Law will be held on Saturday, November 1 at River Alchemy of Creative Arts (2600 S. Flores 78204) at 4:30pm. Doors open at 4pm. Panelists include exhibit curator Victor Barnuevo Velasco and survivors of martial law torture. Facilitated by Myra Dumapias. A somatic healing session led by Sarah Joy Thompson, co-founder of River Alchemy of Creative Arts, will follow the discussion. RSVP here.