Click above to enjoy the Deceleration Podcast. Or join us at Apple Podcasts, iHeart, Amazon Music, Goodpods, or a dozen other platforms.

I can’t remember how or where I met Jack Elder. He was just around in so many of the arts and activist spaces I frequented—often on bicycle, a homemade sign reading “One Less Car” hanging from his trailer. When I worked at URBAN-15 he came by regularly for its Manhattan Short Film Festival. I wouldn’t learn until later, inviting him to reflect on San Antonio’s involvement in the Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s, that he had been convicted on federal charges and sentenced to house arrest for driving refugees from the US-backed wars in Central America to the bus station.

I also came across him in a novel by borderlands writer Carlos Nicolás Flores (interviewed for podcast embedded above), whose character Jack “The Commander” Halligan—a lanky, blue-eyed white guy organizing a convoy of medical supplies down to Nicaragua—was in part inspired by Elder’s work in the Rio Grande Valley on behalf of Central American refugees.* Not until Elder passed away in August 2025 did I learn he was also one of the co-founders of RAICES, originally known as the Refugee Aid Project, in 1986.

According to Rachel Cywinski, for years his Highland Park neighbor, Jack didn’t like all the attention that followed these actions. As he said in another profile of his life and activism, he wasn’t the story. He was simply doing what he believed was right. And he believed in living simply. His water bills were famously minimal, and his home didn’t have AC—except once, Cywinski said, when he learned that his daughter’s friends were declining to spend the night for lack of air conditioning and he didn’t want her to feel left out. He rode his bike or walked everywhere until Parkinson’s made balance too difficult.

I remember him coming by the house for a visit one time in 2019. Okra had been plentiful in our garden that summer and we gave him a bag of it, which pleased him. He followed up with a typewritten letter underscoring his deep commitment to living in ways that minimized harm for Earth and people, which included extended quotes from books he’d been reading and an anti-consumerist ad he’d carefully torn from a magazine.

“Now for [a quote] from Wendell Berry from essays in his book What Are People For?” he wrote to us in 2019. “‘We must achieve the character and acquire the skills to live much poorer than we do. We must waste less. We must do more for ourselves and each other.’

“Neither the Mayor nor any of our civic leaders are capable of dealing with the intractable problem of convincing us to embrace LESS goods, mobility, comfort, you name it,” he continued. “I don’t expect my legendarily parsimonious utility bills to make much of a difference but, like I used to respond to my middle school students when they asked me why I rode my bike to school: ‘because I love my mother (as in Mother Earth).’ And I continue to ride (bike and VIA) because I can do no less for mis nietos Dylan, Dane, Jake, Jaiyah, Emily, Jayannah, Rowan as well as [your son] Wolfgang y todos los demás inocentes.

“I can’t speak well due to Parkinson’s but I will seek out ways to be an ally in this epic struggle.”

A year later, during the pandemic, I invited Jack to share his memories of Laura Sánchez, a fellow Sanctuary Movement activist, for Deceleration. Parkinson’s prevented him from giving an audio interview, but he typed up his memories on his typewriter and dropped off two hand-corrected pages at our house, along with an unpublished story titled “Cangrejal” (PDF).” It was something of an incredible tale—and as with his letters, gave deep insight into the kind of person Jack was.

A work of memoir, “Cangrejal” gave an account of a two-week window in 1968 when Jack knew he’d been drafted but before he was shipped out to Vietnam. Written 50 years later, it tells the story of a young man who returned to Costa Rica to say goodbye to friends he’d made in the Peace Corps there and found his life improbably both threatened and saved. One night, after drinking with friends, he set out for the neighboring town of Cangrejal by foot in the dark, carrying only “an improvised candle lantern” that finally burned out.

Drunk or unlucky, he slipped and found himself dangling over a swift-moving river, caught by “a root sticking out from the bank,” until a group of local men heard his cries for help and hauled him back up the bank. Arriving in Cangrejal, though, the townspeople avoided him: after he’d finished his stint in the Peace Corps and returned to the States, a rumor had spread that he’d been drafted, sent to Vietnam, and killed. “So when I appeared [in Cangrejal], bloody and in rags” from his drunken adventure, “it wasn’t me who people avoided, it was my ghost.”

“It’s been fifty years since that night,” he mused. “Had the root not been there or had it been of insufficient stoutness, all my future thoughts and longings and those of my children, and now of my grandchildren, would still be waiting to be engendered, afloat somewhere in the cosmos. Have I been living a life worthy of what fate or ‘la mano de Dios’ or luck or physics gifted me with that night? Have any of us?”

From the gift of that unpublished story, which opens with another tale about a bar fight in Cangrejal, and from other things Jack shared with us over the years—that he’d acquired Parkinson’s from Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam, that he attended a boxing gym program called Punch Out Parkinson—I got the sense of a person who was outwardly quiet yet inwardly burned with intense anger. Yet via discipline or temperament or spiritual practice he’d managed never to act out that anger in destructive ways; he’d used his anger only for good, in material acts of quiet care.

In 2021, I got a call from local food activist Leslie Provence (also interviewed above) saying Jack had something for us. He’d asked her to call on his behalf because Parkinson’s had made talking on the phone too difficult. So one autumn evening, Greg and I went by his Highland Park house with our son Wolfi, then age two. Something about the visit felt portentous, like possibly it could be the last time we’d see Jack, so when we got home I was careful to record the following details.

When we saw him that night, I could tell his health had declined. He said as much when I hugged him, his back bony. Though he still moved well at that point, his difficulties speaking had increased, and at times he would spell or shift to Spanish when he got stuck on a word. His pride in his front- and backyard wildscapes remained untarnished, though, as he showed us around the life overflowing there: Turk’s cap and Gregg’s mist flower, raised beds full of chiles and sunflower, Mexican plum and papaya and fig trees.

In one corner of the backyard was a compost bin he’d constructed beside some metal trashcans, one filled with finished compost and another with rocks, and beside them a bin of neatly-piled brush and sticks. He’d embedded two paver stones in the Gregg’s mistflower, their once-wet cement engraved with the names of his grandchildren and his age—72 on one, 78 on another, his age at that time.

It seemed like any other visit, but when I asked where he wanted to sit, he said we should go inside. His slow sweet elderly dog Pepper followed, her black fur sprinkled with grey.

I had never been inside Jack’s house before. The kitchen and living area were laid out like a shotgun house, but also built in a way that reminded me of the houses I rented in Kansas: bare wood floors and walls, shabby but neat, intricately decorated with photos of family—five kids and numerous grandkids. Jack took me around the house, proudly showing off pictures.

Not until we were seated on the couch did he get down to business, handing us a thick envelope. I asked: Should we open it later? Or now?

Now, he said.

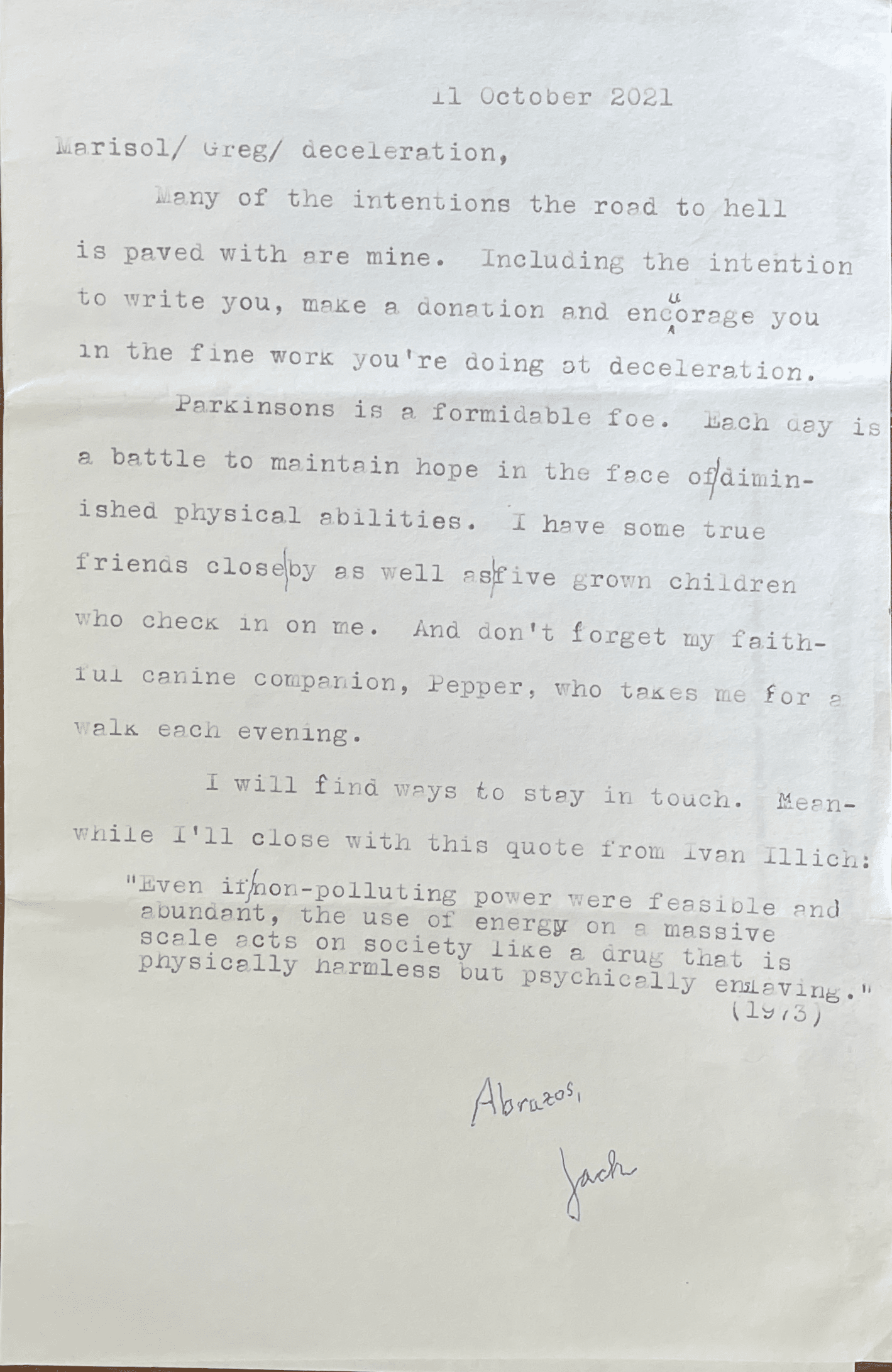

Inside was a small note, typewritten on a piece of recycled paper in Jack’s careful, parsimonious way, along with $600 in cash. It’s for Deceleration, he said. The letter ended with a quote from ecological economist Ivan Illich:

Even if non-polluting power were feasible and abundant, the use of energy on a massive scale acts on society like a drug that is physically harmless but psychically enslaving.” (1973)

From the couch Jack finally told us: he was in the process of giving up the world. He’d been researching VSED, he said, which stood for voluntary stoppage of eating or drinking. It was his simplicity and iron resolve all rolled up into one final gesture, going out the way he wanted to go, before he lost hope altogether or any more of his faculties.

He was still with it though, sharp. Had us try to guess how many stomped soda cans were in a cubic square box next to his couch. The number is a perfect square too, he said, prompting me to eyeball the box and hazard a guess that turned out to be correct. His eyes widened when I guessed it: 625? There was no magic in it, though; 625 was the only square number I could think of that might come close by the looks of it.

VSED would take about ten days, he said; you used morphine at the end. He was still researching it. In the meantime, he was well taken care of; three of his children were in town, and he had neighbors who regularly looked in on him.

A little later I gave him the lava cake we brought over, a symbolic gift to Wolfi for successfully learning how to poop in the potty. Jack ate a bite, then showed me around the rest of the house: his spare bedroom, just a bed and a nightstand and closet, no AC; the bathroom; the addition he built when he had a woman and her son living with him.

At first I thought he meant romantically, but later it occurred to me—on seeing bunks and lofts constructed in each room of the addition—that he may have been sheltering people in the way they did during the Sanctuary movement. In her interview, Leslie talked about their Highland Park neighborhood as an intentional community, formed by the network of relationships between longtime activists in migrant rights and environmental movements. The connection between the two, she said, was voluntary simplicity. A belief in living as close to the Earth as the people one worked to protect.

I know where to send folks if they’re coming through, I said, and he nodded approvingly.

On the wall of the small added bedroom hung the small lamp he’d constructed in Costa Rica, the one which appears in his short story “Cangrejal.” It was of simple construction: a coffee can with holes punched at the bottom and wire fashioned into a handle. You placed a candle inside; the holes kept it from getting snuffed out.

On his bathroom wall hung a photo taken of him from behind, his daughter at two or three fast asleep on his shoulder. And in one corner of the kitchen was an altar with obituaries of his parents, and a shadowbox with mementos of Saint Oscar Romero, assassinated in El Salvador during its civil war.

Notes from this visit record what I think Jack wanted most to be remembered for—not the loudness or bigness or brashness of the actions he took, but the quiet, steady, daily example he provided of what it means to live lightly on the Earth and to care for its many others, from the plants in his yard to those fleeing bombs bought with our tax dollars. He wanted people to know that there was nothing special about the way he lived; anyone could live that way too, if they cared to.

In that way his name “was proper,” as George Cisneros observed in his interview, for “he was an elder,” a teacher not only of children but of all of us, in his day-to-day rhythms in yard and neighborhood a thousand tiny lessons about how to be human amid the vastness of the many injustices we confront. As Jack wrote to us, quoting from an essay by Erik Reese in Harper’s about the poet Robinson Jeffers:

If we do, as a species, survive the coming catastrophe, I suspect it will only be as the small bands of resourceful, food-sharing generalists that Paul Shepard describes in his classic plea, ‘Coming Home to the Pleistocene.’ Heat-absorbing concrete and heat-induced violence will make densely crowded cities unlivable, and the desk-based skills of urban dwellers will prove useless. Instead, we will return to the way we lived for a half million years before agriculture brought on the modern world and all of its maladies. That will be the resurrection of human civilization that Jeffers imagined—a return to our true place in the matrix of life.

-30-

*Note: In the podcast, George Cisneros misremembers the details of two historical events. First, Elder was arrested and sentenced to house arrest not for transporting medical supplies to Central America—although activists in South Texas did organize convoys of supplies to Central America in the 1980s, which became the basis for Carlos Nicolás Flores’s fictionalized account—but for transporting Central American refugees to a bus station. Second, the halfway house where Elder was sentenced, according to fellow Sanctuary Movement worker Stacey Merkt, who was arrested and sentenced alongside Elder, “was not Laura Sánchez’s house at all,” although Sánchez did maintain a safe house for Central American refugees that Jack was involved with. “I think he worked at the Catholic Worker house in the day,” Merkt recalled by text, “but had to spend the rest of his time in the halfway house in downtown San Antonio.”

* This story originally reported Jack’s neighborhood as Highland Hills. It has been corrected to Highland Park.