The View From Here

Climbing the Port Isabel Lighthouse’s narrow, spiral staircase is a rite of passage for locals here, usually done in elementary school on a short field trip and rarely repeated. I’ve ascended it several times since then and did so again for SpaceX’s sixth Starship launch after an invite from a member of Port Isabel’s marketing department. City officials, still awaiting the results of a study of how Starship launches may be impacting the lighthouse’s structural integrity, is interested also in how many people this space can accommodate for prime launch viewing from 70 feet up.

This lighthouse, the only one open to the public in Texas, perches atop a mound in the middle of Port Isabel’s downtown. Built in 1852, it once guided ships into the city’s port and became a lookout tower for both sides during the Civil War. The city decommissioned the lighthouse in 1905 for lack of ship traffic. It now serves as a tourist attraction and symbol for the town. Now, as a potential Starship viewing area, out of caution, the replica fresnel lens—built to resemble and function like the original lens that guided ships into Port Isabel—is now reinforced with wooden blocks.

From the top you can see almost all of coastal Cameron County, also known as the Laguna Madre area, where I’ve lived most of my life. I was priced out of the area due to the changes now plainly visible.

Much of that change has come in the last decade. First it was the wind farms, which stretch from outside Laguna Vista and Los Fresnos then beyond, their countless rotating turbine blades fading into the horizon. SpaceX’s ever-expanding totality near Boca Chica Beach is also visible. The six miles between Port Isabel and the launch pad—separated by Long Island Village and South Bay—seems to shrink each time the company adds a structure. It feels closer, too, as the city’s windows shake from Starship breaking the sound barrier high above.

Port Isabel transforms into an international tourist hub every time Starship launches, just as Boca Chica Beach fills with SpaceX enthusiasts in the days leading up to the rocket’s ascent. Before, during, and after a launch, the newest cars, several of which are Tesla Cybertrucks, and new faces take over Laguna Madre’s streets, gas stations and restaurants. Boats, mostly yachts and expensive fishing vessels, crowd the Laguna Madre bay just before the U.S. Coast Guard’s designated viewing boundary, some of which are private charters for SpaceX employees.

Across the Queen Isabella Causeway, the City of South Padre Island promotes Starship launches as another reason to vacation there, calling itself “your space escape.” The city wanted to go “full bore” in attracting SpaceX tourism, South Padre Island’s Convention and Vistori’s Bureau head Blake Henry told the San Antonio Express-News earlier this year. Hotels on the island, and in Brownsville and Matamoros, are selling out ahead of launch days and obviously welcome the extra business. Realtors continue to sell on the notion that you can see launches from the comfort of your home.

Related: “PODCAST: SpaceX Wastewater, LNG in the RGV, & Sustained Indigenous Resistance“

That’s because Cameron County’s Isla Blanca Park, on the island’s south end, has become the de facto viewing area for Starship launches, with the most devoted of spectators camping out the night before for a spot on the jetties. Those who don’t want to pay the park’s cash-only fee trek there from the city’s public beaches, joining thousands of others vying for an unobstructed view. This includes people setting up on the park’s sand dunes, even if they’re repeatedly told they’re not allowed to be there.

At Boca Chica, the company is adding more buildings as its owner, Elon Musk, creates a company town, or “Starbase.” It’s a name used only by the company, local officials—some of whom are trying to formally designate the name—and SpaceX enthusiasts. SpaceX is building restaurants and recreation for its employees. Parking garages and factory buildings are replacing the earlier tents where SpaceX constructed parts of Starship. And predictably for SpaceX, it built other structures there without the knowledge or regulation of Cameron County.

It’s a continuing pattern for the company. A slide from a 2017 presentation, featured at the time in a New York Times article, shows how SpaceX employees told local officials that the company wanted to build another Falcon 9 project site for the smaller reusable rocket system currently launching from a facility in Florida. But after scoring permits for a facility with a “small, eco-friendly footprint,” the company told Cameron County that they were going to build and launch bigger rockets after all.

Call it a lie, a hint at the future, or merely a change of plans, but that same slide, which includes a photo of launch infrastructure at the company’s Florida site, reads: “SpaceX’s [South Texas] facility will not include the massive launch infrastructure seen in the background.”

In 2020, the Federal Aviation Administration said it would conduct a new Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on the larger site, but ultimately revised the original analysis from 2014 instead. The New York Times reported that the agency let the company do what it wanted because it wanted to help SpaceX’s “bold, grand vision.”

It seems every other agency and local governmental body had similar thoughts when courting the company, with Cameron County giving SpaceX a 10-year tax abatement and the State of Texas offering up $15 million in subsidies. The company now has a separate testing facility down the road and is building a second launch tower next to its original, along with new signage boasting itself in all-caps as the “Gateway to Mars.”

From where I stand at the top of the Port Isabel Lighthouse, the newest local skyline changes are the cranes constructing the Rio Grande LNG (liquefied natural gas) plant just outside of Port Isabel. Viewed from up here, you can see how close these facilities for producing liquefied methane are to SpaceX’s operations. Whatever risks could come from that, local officials and companies haven’t indicated any concern.

Launch Day

Looking at those cranes from the lighthouse’s lantern room, I was remembering how green the wetlands once looked before they were cleared. Then—20 seconds after Starship’s engines ignited—the sound waves made their way to Port Isabel and the lighthouse.

The room has a narrow, circular walkway surrounded by windows, with the lighthouse’s replica fresnel lens in the center. All those windows were shaking now, making the hot, airless room into a sensory nightmare. Nearby seagulls, crows and pelicans flew north towards the Laguna Madre en masse. The lighthouse swayed slightly as car alarms blared somewhere down Garcia Street. Then all the noise stopped, as people in the Lighthouse Square below kept their eyes to the skies for several minutes.

About half an hour later, the traffic of thousands of cars heading back to wherever they came from filled the Causeway. Locals coming home from work and launch tourists alike found themselves stuck on the bridge or at Isla Blanca Park for hours.

For this particular Starship launch, former—and now future—U.S. President Donald Trump traveled to Boca Chica to watch alongside Musk, one of the biggest funders of his campaign. And while the rocket made it to space on its 6th launch, just as it had in three previous launches, the rocket booster that sent it there exploded in a “landing burn” into the Gulf of Mexico, while the rocket itself splashed into the Indian Ocean upon return from orbit.* Watching this, I couldn’t help but imagine this failure as the rocket booster falling victim to performance anxiety in front of the incoming president. The real reason was SpaceX losing contact with the launch tower computer that would’ve guided it down.

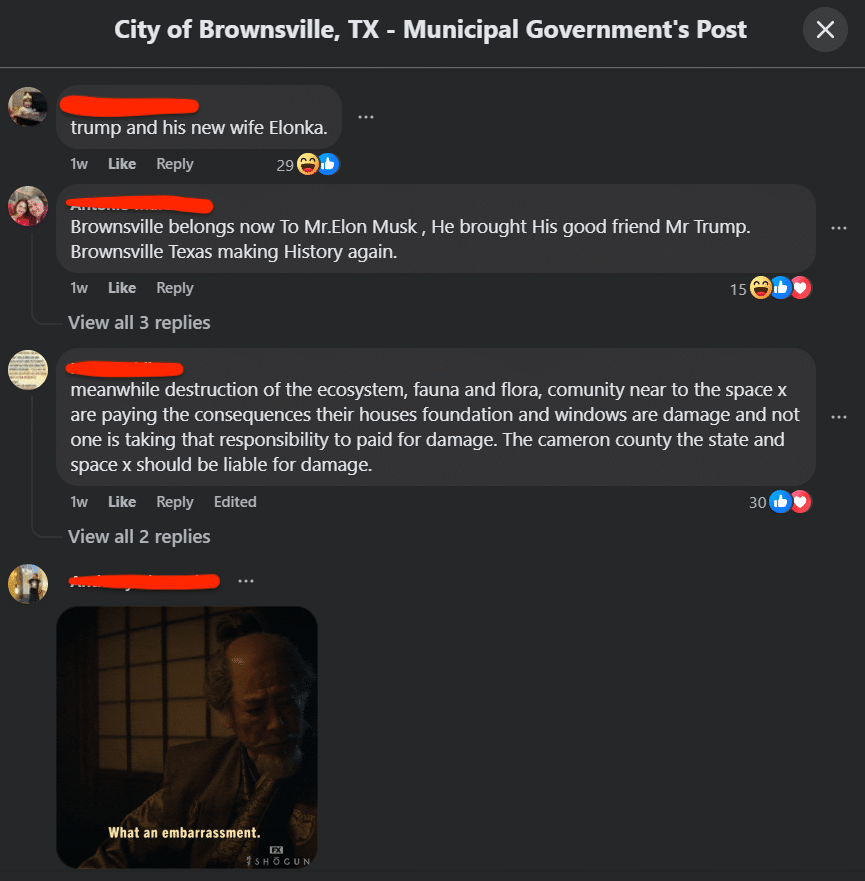

On social media, Brownsville Police would brag about being in the motorcade that brought Trump down Highway 4, the lone road to SpaceX’s South Texas facilities and Boca Chica Beach. The City of Brownsville similarly used the launch to boast about Trump’s visit and boost SpaceX broadly:

“SpaceX continues to innovate and push the boundaries of what’s possible,” they wrote on Facebook. “Their efforts continue to make history and contribute to our community’s growth as a hub for space technology.”

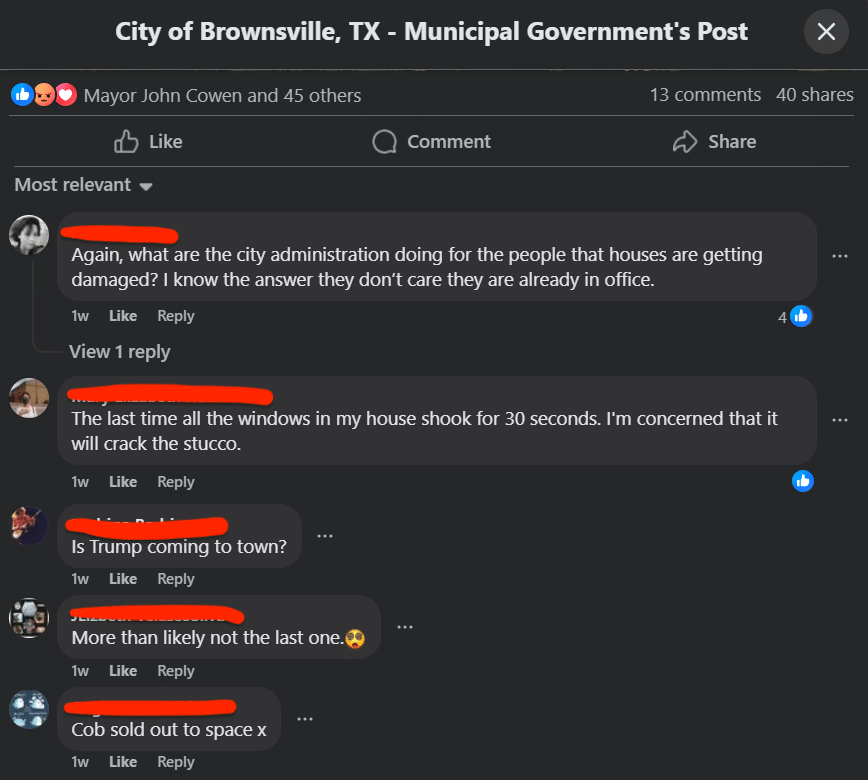

Some residents were more direct concerning the boundaries SpaceX was pushing locally.

“Roll the red carpet for billionaires playing with their toys in our backyard,” one Facebook user wrote. “Brownsville PD are just servants to Elon Musk and Trump. Brownsville local government [is] corrupt as hell lol.”

What the City of Brownsville’s official posts neglected to mention is Trump’s plans to activate the largest deportation event in the history of the United States or Musk’s technocratic vision of the future, both of which now coincide in the Rio Grande Valley. The Trump administration says its first round of deportations will focus only on undocumented people with criminal records.

But to the Trump administration, legal status seems to matter less than where people came from. Or to quote Stephen Miller, Trump’s deputy chief of staff for policy: “America is for Americans and Americans only.”

So while this Starship launch, the first after Trump’s election, ultimately didn’t turn out as SpaceX planned, it didn’t matter. The launch unofficially inaugurated the Rio Grande Valley’s place as ground zero for the incoming president’s deportation campaign.

The same day of the launch, Texas Land Commissioner Dawn Buckingham offered Trump over 1,400 acres—the size of about 78 White Houses—in the Valley’s Starr County for a deportation facility. Tom Homan, Trump’s pick for “border czar,” said the administration would “absolutely” use the land and visited the RGV as recently as this week.

There is no doubt that Musk, soon to play an advisory role in Trump’s administration, who has inserted himself in U.S. immigration politics and spreads white nationalist conspiracy theories, will meddle in the Valley’s role in receiving asylum seekers and migrants and their expulsion. Musk and Trump also appear aligned on the desire to deregulate industry and suppress dissent.

The City of Brownsville seems to have already attempted to do the latter when it comes to SpaceX. In 2023, Brownsville police arrested local organizer Bekah Hinojosa for allegedly spraying anti-SpaceX graffiti on a mural paid for using Musk Foundation money. Then-mayor Trey Mendez, a fan of Elon Musk and real estate developer, subsequently doxxed Hinojosa on his Facebook page before backpedaling after the many in the community called him out publicly for his behavior. Many in the community believe Hinojosa’s arrest was a targeted attempt to quell local resistance to the company.

The overarching sentiment of the public comments was that graffiti, a misdemeanor, was being treated as more of a threat to the community than rising housing costs, militarization, and privatization in Brownsville. Starship launches have always meant, to the people in office locally, a chance to reorient the area in a way that benefits the most powerful residents. The chance to go to Mars means little to those who can barely afford the costs of inhabiting Earth, many of whom call Cameron County home.

‘Booms’ & Damages

“We got a good view [of the launch] from our backyard,” a friend of mine texted from the Tarpon Field neighborhood. It was the first message I saw after the rocket’s noise ended. “But it knocked my niece’s window off the frame.”

For years I’ve heard stories like this. After the second suborbital launch, a friend’s ceiling cracked in their older home just off Highway 100 in Laguna Heights. Former Boca Chica Village residents have told me the cracks in their foundation appeared only after Starship prototypes ascended in 2019.

The New York Times got wind of this phenomena via a professor studying how this area was faring under launches, reporting that the sound waves coming from Starship’s sonic booms—specifically its booster upon return to Earth—are much stronger than the FAA projected they’d be, leading to possible structural damage to homes. A study done for the City of Port Isabel found similar results.

The City of Brownsville and Cameron County now warn of sonic booms when announcing upcoming SpaceX launches. With those posts come comments from residents asking if the city will cover damages to their homes. Posts congratulating SpaceX for successful launches are met with even more scorn.

SpaceX seems to have predicted this inevitability of local damages a decade prior. The company lobbied Texas lawmakers into passing a law that prevents residents from suing the company for property damages due to rocket launches. It followed passage of a new law that made SpaceX’s presence in Boca Chica possible to begin with— written by Texas Rep. Rene Oliviera of Brownsville, HB2623 closed state public beaches for “space flight activities.”

The most recent launch came just a few days after Bloomberg News reported that SpaceX had backed out of a land swap deal this past summer. For 43 acres of disconnected land in Boca Chica, the state was supposed to receive nearly 500 acres of land near Laguna Vista, a community west of Port Isabel. The land borders a Cameron County park facility, the South Texas Ecotourism Center. The park, opened in 2019 as a project led by Cameron County Commissioner David Garza, showcases the flora and fauna of the lower Laguna Madre area.

Garza and Cameron County Judge Eddie Treviño Jr. were initially upset with the landowners and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) when they first learned details of this deal. At that time, the county was negotiating with the owners of the same acreage to expand the park and add walking trails to another section across the highway facing the Laguna Madre.

After some politicking with the state agency, the county decided it would support the SpaceX land swap now that it had a role in how that land would be used—most of it for conservation. This past March, TPWD Commissioners voted unanimously to approve the swap, despite overwhelmingly negative public feedback from people who live in the RGV. The resistance wasn’t about the land loss itself, it was about SpaceX once again getting their way, as best summarized by Sadie Hernandez, a Brownsville-born organizer who spoke to TPWD and local leadership directly during the meeting’s public comments period.

“It seems to me that the folks who are interested in this land swap, while disregarding people here, are more interested in the validation and the fantasy of pretending they’re rubbing elbows with Elon Musk over people that live in the community,” Hernandez said.

With SpaceX backing out of the deal, the county has to start its conservation efforts over again—this time without federal funding. Garza, in an interview with the Brownsville Herald, said that the ordeal had him questioning his original vote for SpaceX’s tax abatement. He said that defending the company from its critics was getting more difficult, especially given that SpaceX gave no reason for pulling out of the deal.

“I’ll probably be thrown out of the county for making these comments, but I don’t care,” Garza told the Herald.

That tax abatement with SpaceX ends this year, too. That means the company will now have to pay its full share of taxes to the county for the first time in 10 years. SpaceX, which represents less than 2 percent of the county’s total workforce according to U.S. Census data, claims it’s brought billions to the local economy, though it has never explained how it calculates this. From my view, other than new restaurants downtown, more chain and retail everywhere else, Brownsville is largely the same as it was 10 years ago.

It’s worth remembering that the Port Isabel Lighthouse was constructed as the nation lurched toward civil war in the middle of the 1800’s, its existence a testament to how storied this area is, and how quickly the tides can change. It’s an artifact of the latter end of a longer colonial history, imposed on an area where people have lived for millennia, long before SpaceX, long before space travel, long before histories of European settlement itself.

SpaceX, which is imposing itself on the Laguna Madre, an area that is more culturally Veracruzano than Texan, that looks more like the Florida Everglades than the Wild West, should consider how it is merging with that history. The lands and waters here are no stranger to waves of people crashing from across the world who have come here to escape persecution, poverty, or forced military conscription. Who settle for a minute for a Spring Break blowout or stay for decades to study the land's ecology. But SpaceX’s presence only extends a century-old tourism economy, one that chronically caters more to those who visit these lands than those who actually live here.

The Rio Grande Valley is the set of an experiment for SpaceX’s Starship that itself is merging with Trump’s second, more punitive round of immigration policy. As local officials begin to doubt whether SpaceX was worth the welcome they gave it, the facility spreads, collecting lawsuits, changing the culture of the Brownsville metro, and the ability of people to live here.

Garza saying he’d be thrown out of the county for saying what he did is an interesting tell, one that seems to prove out what organizers opposing the company’s will have been saying for nearly a decade: that SpaceX does whatever it wants because no one in power speaks against it.

As I stare at its growing facilities from up in the lighthouse, it’s unclear to me how SpaceX will move into the future. The company never totally reveals what it’s planning. I know it will grow. I know that the haze from the launches will get more frequent, as the company plans to send up at least 25 rockets next year and each year thereafter. What I cannot see is how it ends: whether local resistance and lawsuits could outflank the company’s growth plans, whether officials will ever see SpaceX other than as a godsend. I don’t know if Musk will get to Mars from Boca Chica. But I know the rest of us won’t.

-30-

* Correction applied on Dec. 3, 2024: The story originally reported that the booster rocket “exploded and fell into the Indian Ocean.” Deceleration regrets the error.