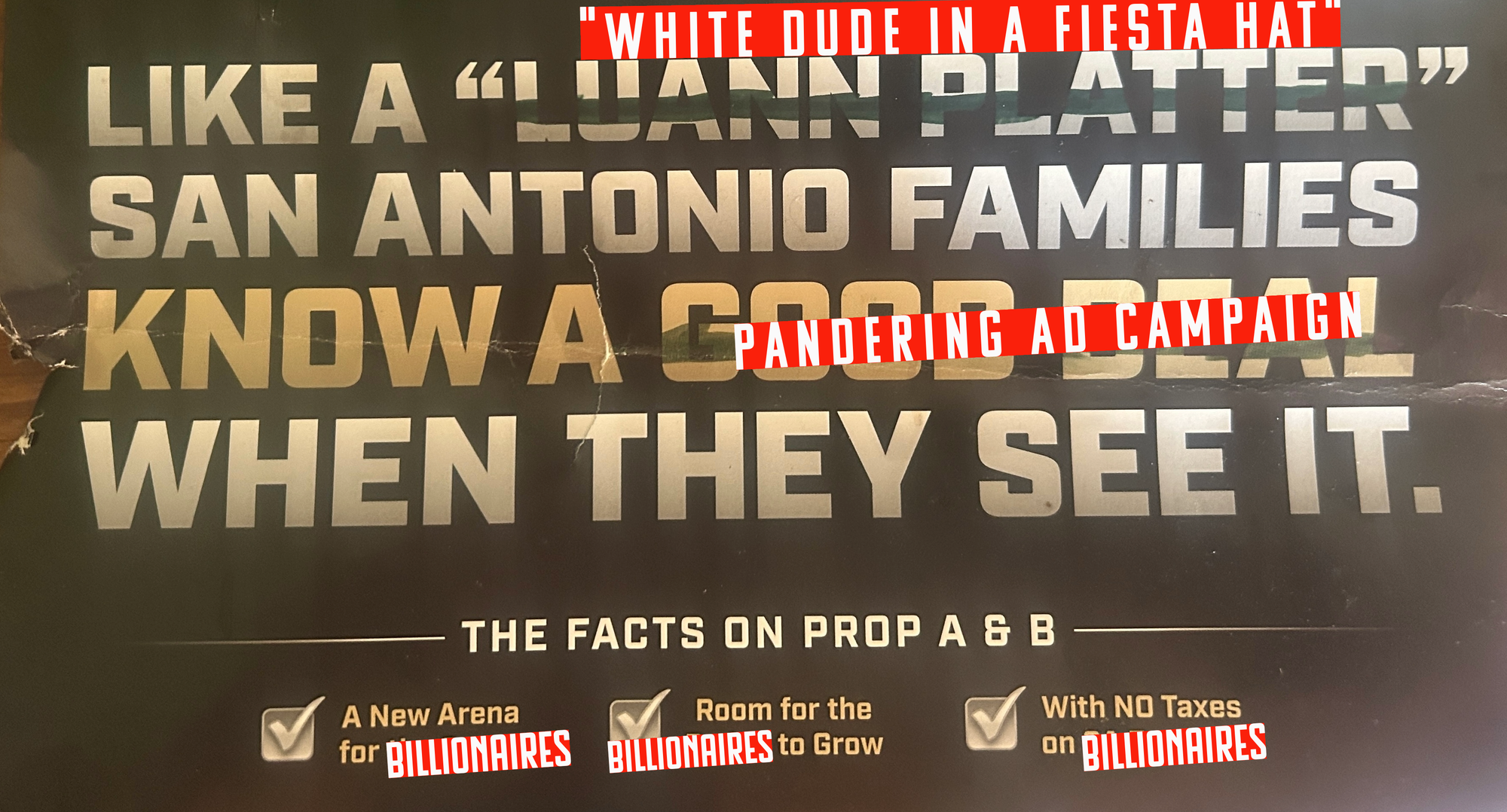

Editor's Note: Though this essay by historian Daniel Wortel-London gets somewhat into the weeds of New York City's political history, the larger point is an important one as we move into the last week of early voting on Project Marvel. In short, city leaders in New York City have been trying for a very long time to meet the needs of everyday residents by providing corporate welfare to the richest companies, in the hopes it'll pay off in the form of taxable wealth. But it's an economic theory that hasn't borne out, according to Wortel-London. This is no less true in San Antonio, where trickle-down economics have been the policy du jour for decades now. In the City's latest attempt, Project Marvel requests that Bexar County voters approve an increase in the county visitor tax—not for housing or hunger or public libraries or parks, but for elements of a $4B sports-and-entertainment megaproject that will relocate the Spurs arena from the Eastside (where City and County officials falsely promised the same trickle-down revitalization a generation before) back to downtown (where the Spurs arena used to be before it was relocated to the Eastside). Even worse, Marvel boosters have shamelessly exploited the hometown pride of San Antonio's largely working-poor residents to drum up support for this busted theory that channeling public money to the Spurs' billionaire owners will ultimately benefit all San Antonio residents. As voters head to the polls, it's good to take a step back and see the questions before us from a historical perspective. What happens here is not unique to San Antonio, and as such we can learn much from struggles elsewhere to imagine and enact other models of ecosocial wellbeing. Till then, early voting in Bexar County continues through October 31, and election day itself is November 4. Visit the Bexar County Elections Department online for a sample ballot and more info on where and when to vote. —Marisol Cortez

In 1979, a few years after New York’s fiscal crisis, New York City mayor Ed Koch posed for a photograph alongside Donald Trump. Mayor Koch despised the welfare state and cut it severely during his tenure. He also partnered with developers like Trump to promote real estate growth, in the hope that it would prevent another fiscal crisis. His mayorality, for many people, represents the beginning of modern urban politics: subsidies for the rich, trickle-down for the rest.

But the problems of modern inequality don’t begin under conservative mayors. It began with progressives in the early 20th century, liberals who assumed that subsidizing the wealthy and building the welfare state weren’t contradictory, but complementary. Taxing the rich would help pay for generous social services.

But while their intentions were admirable (and we should still tax the rich, don’t get me wrong), their policies also entrenched the power of the elite over urban economies and politics in a way we are still paying for today.

That’s because liberal economists made two flawed assumptions: they assumed that elite-driven growth pays for itself, and that there’s no alternative economic system for cities.

But what if the costs of elite-driven growth outweighed its benefits? What if relying on the rich to “take care of everyone else” was neither politically nor financially sustainable? What would this mean for how we interpret the history of liberalism and the welfare state? And most importantly, what does this imply for how our communities should develop economically?

These are the questions my new book, “The Menace of Prosperity,” pursues. It’s a history of modern urban economic development told through stories of struggle over the costs of elite-driven growth in New York City between the late 19th and late 20th centuries. It makes three arguments: first, that elite-driven economic growth has often led to great economic costs. Second, that generations of activists have promoted economic alternatives to elite-driven growth models. And third, that liberal advocates of elite-driven growth strategies came to dominate postwar New York—and arguably, the country—not by delivering economic development, but by obscuring both elite-driven growth burdens and its alternatives.

With all this in mind, I want to provide some case studies from my book tracing how New York’s fiscal imagination changed between the 1870s and the 1970s, trace how these changes alter the way we understand American history, and conclude with some thoughts on my story’s implications for us today.

Questioning Progress

We’ll start with the 1870s. During this decade, one out of five American cities went bankrupt. This was partly a national issue—the stock market collapsed. But at the city level, many local development decisions also went awry. New York depended largely on the property tax for revenue during this time, and it tried to raise this revenue by raising property values. The city sold public land, spent money on street improvements, and went into debt to finance grand infrastructure projects. But values didn’t rise quickly enough. After the stock market collapse, banks asked for their money back and New York couldn’t pay up. This led to a large revolt against debt-financed improvements during the 1870s by worker-activists who felt that cities were subsidizing speculative landlords at the expense of workers.

This critique was translated into policy by the economic theorist Henry George. George argued that the effort of cities to raise the value of land was actually costing them enormously, as high land values made it harder for employers to erect factories and workers to build homes. Progress was creating poverty. By taxing away the value of land, however, land could become more affordable for housing, productive factories could emerge and generate employment, and cities could be financed without burdening the worker. And to accomplish this land value tax, George sought to rally workers, small businesses, and productive capitalists against speculative financiers and parasitic landlords. And for a time, as my book goes into, he was quite successful.

But George wound up being outflanked by a broader convergence among liberal municipal finance officers and planning officials. By “liberal” here, I refer to the more modern sense of the term: an ideology which was often positive towards regulation or even redistribution, but believed in taxing rather than supplanting the conventional “for-profit” sector as a way of financing their progressive state.

And where Georgists had seen real estate’s “progress” as causing poverty, these corporatists believed taxing such “progress” would help reduce poverty through the new welfare expenditures that tax revenue enabled.

Rather than expropriate landlords and reduce land values, these liberal officials aimed to subsidize them and raise property values for the sake of the welfare expenditures that tax revenue would create.

This fiscal imaginary, with its virtuous cycle of subsidy, growth, taxation, and public-spirited expenditure, was at the core of the modern liberal fiscal imaginary. This imaginary would be promulgated through economic textbooks, converted into budgetary practices which insulated economic development decisions from democratic oversight, and implemented in city-planning policies like zoning. And while these strategies provided the fiscal bulwark for the local welfare state in the 20th century, they also marginalized the radical alternatives that had emerged during the Gilded Age.

Public Ownership

Another example of how liberalism constrained creative development strategy was the case of profitable public ownership. Today, we often think about public ownership in terms of service provision, but many reformers in the late nineteenth century also provided economic arguments for such ownership. On the one hand, owning profitable enterprises in transit and power could help the city earn profits while providing better services than those provided by the private sector. On the other hand, by generating its own profits, the city would have less need to tax productive businesses or workers for revenue.

This was a direct challenge to the liberal model of economic development, by which the private sector earns profits and the public sector taxes them to provide public services.

An example of how this debate shaped social polices was the case of public housing during the Great Depression. During the 1920s, New York promoted housing for the wealthy and some small homeowners. This didn’t save the city from a fiscal crisis, and by the 1930s, the city was rife with vacant lots, empty apartments, and closed banks.

It was in this economic context that public housing advocates made a novel economic argument for their policy. Not only would construction jobs and lower rent aid the economy, but banks could invest in that housing and be sure of repayment by way of the rent raised in the projects. Rents from public housing, in other words, could help salvage the financial industry—and when those bonds were paid back, those profits could make these projects self-sustaining.

But a lot rode on whether there would be enough rent—enough profits—in public housing. The original housing advocates wanted a mix of incomes in their housing, with the better-off helping cross-subsidize the former to help back the housing bonds and render their projects self-sufficient.

But public housing for middle-income residents was largely outside the era’s consensus. After the crash, the suburban real estate sector begged the Federal government for bailouts to help build housing for the middle-income population, and they didn’t want public housing as competition. Many liberal policymakers agreed: they believed public housing should only aid those who were left out of the conventional profitable housing market, not become a profitable developer itself. In the end, public housing became largely reserved for the poorest Americans.

Here again, we see how the liberal distinction between the profitable private sector and the money-losing public sector helped constrain the scope of public policy in this country. Lost was the mixed, purpose-driven enterprise of profitable public ownership, which had captured the imagination of past radicals.

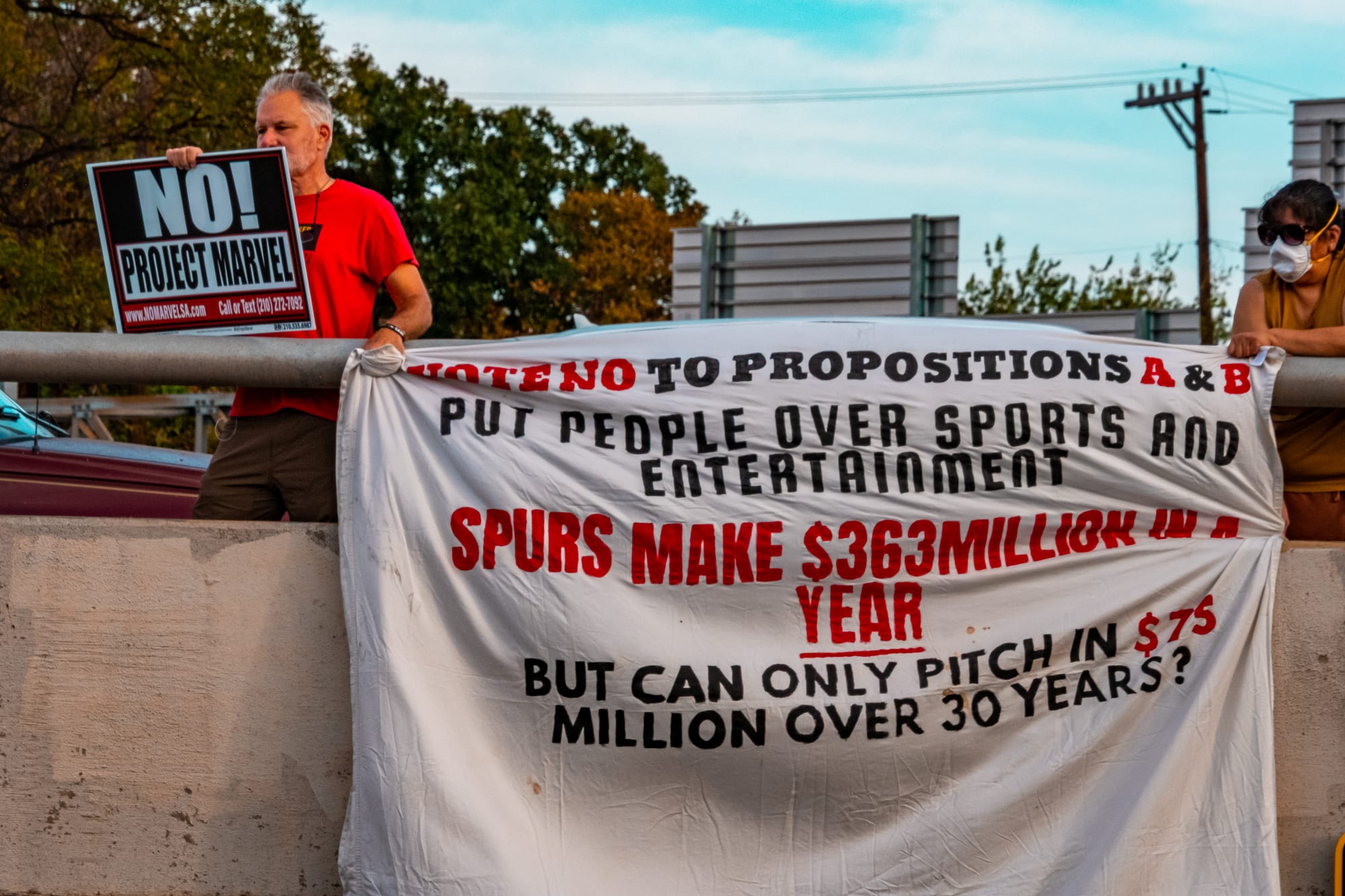

Banner Drop

A small group of residents made their opposition to Project Marvel known on Friday afternoon, dropping two banners of the Nogalitos bridge over Interstate 35. Images: Greg Harman

Fiscal crisis

Finally, we can look at how the liberal embrace of elite-driven “progress” helped lead to the 1970s fiscal crisis and constrained what came after. During the postwar period, bodies like the Regional Plan Association of New York worked with liberal mayors like New York City’s Robert Wagner to promote the city as a corporate headquarters. The city combined this developmental strategy with an expanded welfare state in the hope that taxing corporate firms would help to pay for social services. And while critics like Black power advocates and Jane Jacobs voiced neighborhood-oriented critiques of this model during the 1960s, it remained the city’s consensus strategy through most of the decade.

And then, once again, came the fiscal crisis. We’re used to thinking of the fiscal crisis as due to either an over-generous welfare state or larger economic issues beyond the city’s control. But activists at the time pointed to the city’s corporate welfare state, not its social welfare state, as exacerbating Gotham’s situation. The commitments of corporate firms towards national rather than local markets made them liable to move from the city at the slightest opportunity, which they did in growing numbers in the early 1970s. Those corporations that did stay were vulnerable to recession by virtue of their exposure to global financial fluctuations—and this, by extension, made city finances more vulnerable. New York’s municipal debts were also largely in the form of corporate subsidies as well: as economist William K. Tabb complained at the time, New York’s “capital budget debt…owes far more to the Banker-real estate developer agencies…than it does to helping the poor, more to subsidizing commuters than to helping the unemployed get jobs.” Even the city’s costly welfare services, critics argued, were themselves not so much a driver of the city’s fiscal crisis as a downstream product of the private sector’s irresponsibility and power—their power to pay low wages, charge high rents, and deny investment to needy communities.

In all these ways, the city’s obsession with attracting and retaining corporations and raising real estate values had backfired.

But while the fiscal crisis of the 1870s and the 1930s had led to dramatic campaigns to transform New York’s development strategy, there was less of this after the 1970s. Why was this?

Partly, it was because the politics and costs of private growth were more obscure and depoliticized than in the 1870s. The sheer inertia of New York’s postwar developmental policies, weighing the city down with sunk costs in the form of repair bills and interest charges, made dramatic shifts in economic development policy more difficult than in the past.

Perhaps most importantly, many white people preferred to blame the city’s welfare state, and by extension the city’s racial minorities, for New York’s fiscal crisis. This was an interpretation many businesses were obviously quite happy with, as assaulting the welfare state promised to both lower their tax bill and deflect blame for the city’s fiscal crisis.

And that’s roughly what happened. Rather than jettison their pre-crisis development strategies, New York’s governing class accelerated them—while jettisoning the welfare state.

The speed and brutality of New York’s assault on this welfare state has led many scholars, then and now, to frame the crisis as the triumph of “fiscal logic” over social good.

But such a framing ignores how earlier radicals had used “fiscal logic” to critique earlier crises and provide alternatives, such as Henry George’s critique of elite-driven “progress” and profitable public ownership campaigns.

We should not, therefore, interpret New York’s fiscal crisis as marking the rise of economic growth as an urban policy goal. Rather, we should see it as marking the bankruptcy of economic thought and policy.

All this suggests three ways we should revise our understanding of American history. First, distinctive economic strategies were essential, and not peripheral, to the growth and success of democratic social movements between the late 19th and late 20th centuries. Second, the marginalization of these movements was partly due to the marginalization of the economic visions and practices that underpinned them. And finally, it suggests that the rise of inequality and corporate oligarchy after the 1970s is a product not of thinking about the economy too much, as is sometimes thought, but of thinking about it too narrowly.

Conclusion

Now that would be a bit of a downer to end the story here. But as I finished the book, I was involved in a number of campaigns to help expand our fiscal imagination in the present, from the Wellbeing Economy Alliance to the Democratic Socialists of America, and these movements are only increasing today. We’re seeing it everywhere, from “new municipalist” efforts to win public control over businesses, embodied by Zohran Mamdani’s New York City mayoral run, to the growth of non-profit enterprises, to a surge in postgrowth and degrowth macroeconomic strategies, and much more. Capitalism is no longer hegemonic in our time—neither should it be in our studies.

With that in mind, I want to extend an invitation for all of us to expand our fiscal imagination. We can study how marginalized groups, in different contexts, have attempted to wield economic thought and tools to meet their needs across time. We can re-read works of philosophy with an expanded economic imagination, considering what it would take to translate our ideals into economic reality. We can think of how government institutions, social movements, and power relations have narrowed or expanded different ideas of “the economy.” And by reconsidering how different economic practices have historically contributed to—or detracted from—social well-being, we can better understand the possibilities for reimagining economic and social structures in the present. What precisely these are, and how they can be realized, is not yet completely known to us. But, to risk a pun, there are worse things on which to speculate.

-30-