The first toxic tour of San Antonio I ever took I was also supposed to co-lead. In 2009, I had just been hired by Southwest Workers Union as their first climate justice organizer, and we were hosting a coalition of youth climate groups for their annual convening, showing them around the city. I’d only been back in town a few months, so it was a kind of trial by fire; mostly I followed the lead of SWU’s then-director Genaro Rendón.

In 2009, our tour started near Probandt Street and Highway 90, roughly where the Southside begins, opening with a cluster of noisy, noxious, and often reeking industrial facilities down the street from my Lone Star neighborhood duplex that have since been shuttered—an auto recycling facility, a rendering plant, a gas-fired power plant upriver from Mission Concepción—and ending with the toxic legacy of former Kelly Air Force Base.

From the missions to Kelly, I remember Rendón saying, San Antonio’s history of toxic pollution is inextricably tied to its history as Military City, USA.

At that time fresh out of high school, SWU’s now-executive director Diana Lopez grew up “at the end of the runway” near Kelly Field. She spent summers playing in Leon Creek, which runs through the former base and for decades served as its repository for the degreasing agents, paint removers, and other solvents used for cleaning jet engines. By the time Lopez joined SWU as a high school intern, the organization had been working since the 1980s to document the many health problems reported by union members who lived near the base: high rates of cancer and ALS, repeated miscarriages and preterm pregnancies.

Twenty years later, an environmental justice tour of San Antonio still begins and ends on the city’s Southside, below what Public Citizen organizer Debbie Ponce calls “the red line of inequity.”

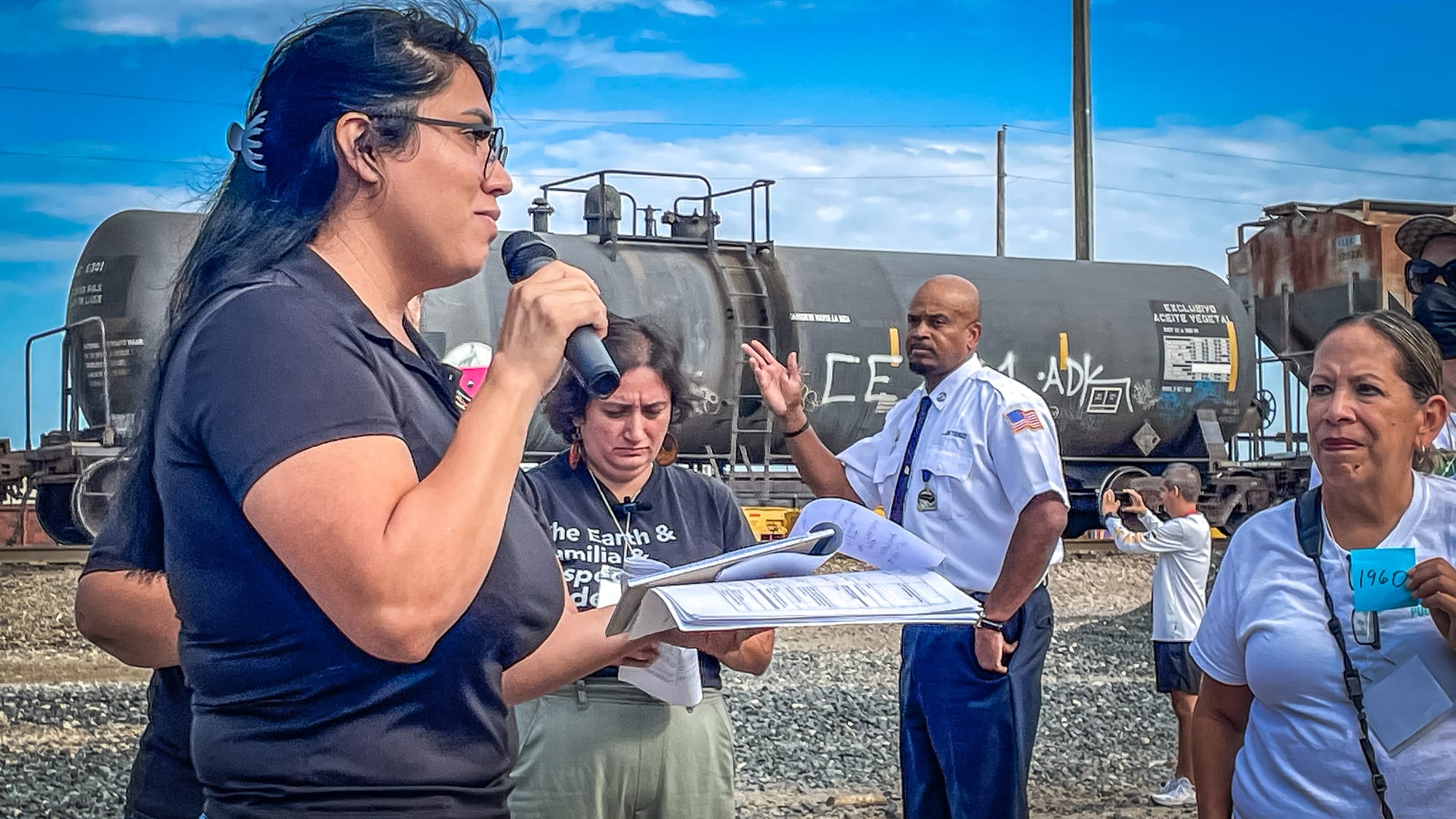

To illustrate, she displayed the map for our tour bus, packed full with around 60 attendees—neighborhood folks, EJ organizers, members of the media, city and county officials and staff—shortly after we departed across from Lackland Air Force Base, next door to where the City turned an old landfill into Pearsall Park. Of the city’s 10 biggest emitters of greenhouse gases, Ponce said, eight are clustered below Highway 90. Of the city’s 14 air quality monitoring stations, only two lie below this line.

These unequal distributions—of pollution and protection both—are classic cases of environmental racism, but they also tell a story of the Southside’s key role in local movements for environmental justice for the last three decades. Ponce remembers growing up on Mayfield Street, near Kelly, and being instructed by her mother to hold her breath when they rode down a particular stretch of Quintana where they would see “the barrels” stored behind the fenceline of the base:

“My mom would say, ‘tienen esqueletos’ [i.e., they have the skull and crossbones symbol on them; they’re toxic]. I don’t remember the skeletons on them. I just remember the stuff coming out of them, and the horrible smell.

“So as we were coming home in our blue Gremlin, we’d go down [the street] just like we came, and as we got to the bridge, my mom would make all of us in the car hold our breath. And we were not allowed to release our breath until we got all the way to Fenfield. That’s when my mom felt like it was safe enough to breathe.”

Co-organized by nine organizations—SWU, Public Citizen, Society of Native Nations, Carnalismo Brown Berets, Keep South San Antonio Proud Neighborhood Association, the Sierra Club Lone Star Chapter, EcoSA Collaborative, Climate Justice SA, and Eco Centro—the tour traced the geographically disproportionate siting of polluting facilities on San Antonio’s Southside but also the accumulation of multiple toxic land uses over time.

Starting just outside the bounds of the former Kelly Field, we began in the 1960s with a memorial for all those impacted by Kelly’s contamination of local soil, air, and groundwater, a plume of TCE that became known as the “toxic triangle.” Deboarding the bus, attendees crowded beneath a painted banner planted at the top of a small hill—“Polluted Communities Equal Stolen Futures”—which overlooked a field of small white flags bearing the names of neighbors sick or deceased. At bottom were portraits of longtime environmental justice activists from the neighborhood who have since passed, including Robert and Lupe Alvarado (see Deceleration’s interview with the couple from 2021 below).

Given Kelly’s importance as a vehicle of economic mobility for Chicanxs on all sides of town, its environmental health impacts have likewise exceeded the immediate footprint of the base. George Cisneros, a tour attendee who grew up on the Westside, recalled how his tío Memo died “a horrible death from leukemia” after working for 16 years at the Lackland golf course upon returning from Vietnam.

“Six feet below his workshop,” Cisneros said, “they found hundreds of 55-gallon oil drums filled with toxic waste. … All the workers who worked at Lackland golf course died of cancer.”

“Tío Memo, ¡presente¡” Lopez called out to the bus passengers, who murmured their response, nodding—so many others had similar stories in their own families. I thought of my own maternal grandmother’s brief employment at Kelly, wondered about my own family’s history of blood and brain cancers.

After Kelly’s closure in 2001, the impacts of “legacy pollution” were overlaid by “new layers” of exposure, Lopez said, when the base privatized as Port San Antonio in 2012 (which also ended any sort of public oversight of cleanup efforts, conveniently).

An industrial business park, Port SA has brought an explosion of “planes, trains, and trucks” to the neighborhood, Lopez said, alongside open air storage for silica sand used in oil and gas operations and other paving material. Now it is mostly “large granule” materials stored on site, Ponce said, “but the ones that were here in 2019 were tiny, tiny. We didn’t know what it was. We just knew it was airborne and would go all over the cars.”

In much the same way, a proliferation of poorly regulated auto and metal recycling facilities in recent decades have added to the neighborhood’s air pollution burden, specifically via a form of particulate matter known as auto shredding residue (ASR) or “fluff.” A fifth-generation resident of the 78211 zip code who has also traced her ancestry back “before the Missions,” Cheyenne Rendón of Society of Native Nations remembered the snow-like substance that covered vehicles and yards after repeated fires at nearby metal recyclers. “I knew it wasn’t something natural,” Rendón said, “and I knew it wasn’t snow.”

A “mishmash of shredded stuff … fine enough that the wind can pick it up and blow it into someone’s yard, someone’s lungs,” ASR “fluff” turned out to be “a policy loophole,” Thompson neighborhood resident Larry Garcia told our tour bus.

After Monterrey Iron and Metal (since rebranded as Monterrey Metal Recycling Solutions) caught fire in November 2023, residents of the Thompson, South San, and Quintana Road neighborhoods began organizing to update city code, with several neighborhood representatives joining a City task force created by District 5 Councilwoman Teri Castillo in March 2024.

Meeting from September 2024 through April 2025, neighbors won a “1,000-foot distance clause”—an update to code prohibiting any new auto or metal recycling facility opening within 1,000 feet of an existing facility, according to the ordinance Council adopted in May 2025—which Rendón described as “crumbs.” The more important victory, however, has been “an acknowledgment of ASR” in the city code, Garcia said, and with it the possibility of closing the loophole that has allowed recycling facilities to spew particulate matter into neighborhoods unregulated.

The end of our tour ventured south of New Laredo Highway’s back-to-back recycling yards, the city unwinding itself into brush and blue sky and undeveloped land. Almost—on one of our final stops, we idled outside the Milton B. Lee gas-fired peaker plant in rural Bexar County, connecting “the things we can see,” as Lopez said, meaning the local concentration of polluting facilities in Southside neighborhoods, to “other layers that we can’t [see], like climate change,” driven by the burning of fossil fuels for power generation, as at Milton B. Lee.

In connecting the dots for tour attendees between toxics and climate, Public Citizen’s DeeDee Belmares recalled that even at Mission Park Burial, where she goes to visit her parents’ grave sites, you can see the city’s sole refinery (plagued by spills and explosions over its decades of operation) flaring over the tops of cemetery trees. Even in their final place of rest, Southsiders can’t escape being dumped on.

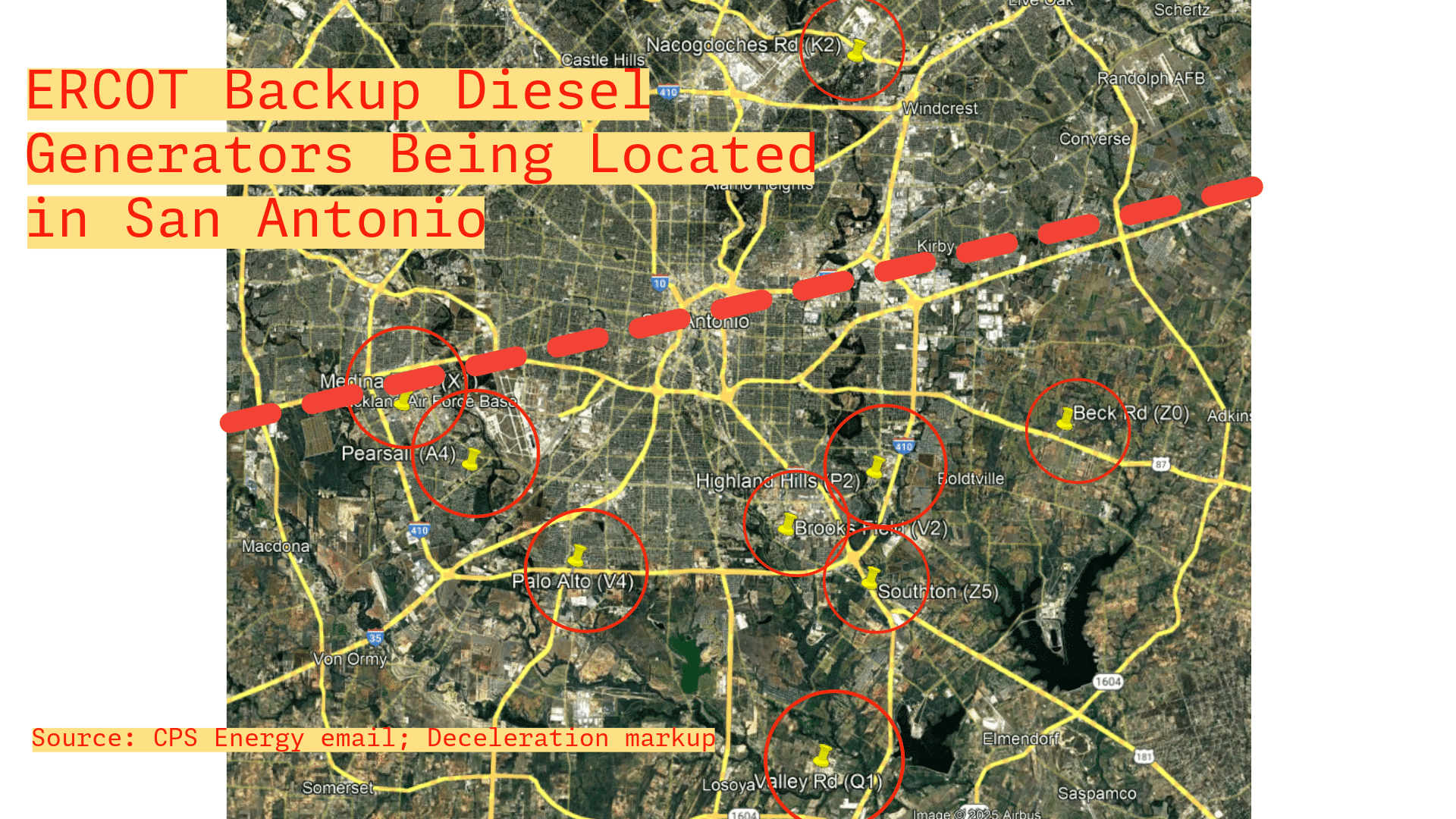

And yet the pattern of treating the Southside as sacrifice zone persists, even in 2025. The final community speaker, Sharron Brown, detailed plans by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, the state’s grid operator, to relocate 15 massive diesel-powered generators from Houston to San Antonio. At 30MW each, they would produce enough electricity to power 30,000 homes in times when extreme weather threatens grid collapse, as during Winter Storm Uri in 2021.

As reported in the Texas Tribune in February 2025, these generators are intended to serve as temporary backup sources of power for the state following CPS Energy’s plans to retire two aging gas-fired plants, especially given “increasing demand for power across the state.” Notably, ERCOT nixed proposals to address grid reliability shortfalls with battery storage instead of much dirtier diesel power. Equally notable is what goes unstated in references to “increasing demand”—the bottomless hunger for power and water posed by AI-driven data centers and their lobbyists, including here in San Antonio.

“Do we need these diesel generators in emergencies?” Brown asked tour attendees. “We need power, yes. I have family members that rely on CPAP [continuous positive airway pressure] machines. But do we need something harmful with emissions? No, we don’t.”

In emails shared with Deceleration, community questions to CPS Energy about where exactly these generators would be located produced a letter sent to customers living within a mile of each generator, forwarded by CPS Community Relations Advocate Jess Copeland, along with a map of locations. Of the nine CPS substations slated to receive a diesel generator, one is located on the Northeast side, near a cement plant ranked as one the city’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters.

The other eight lie below that red line of inequity.