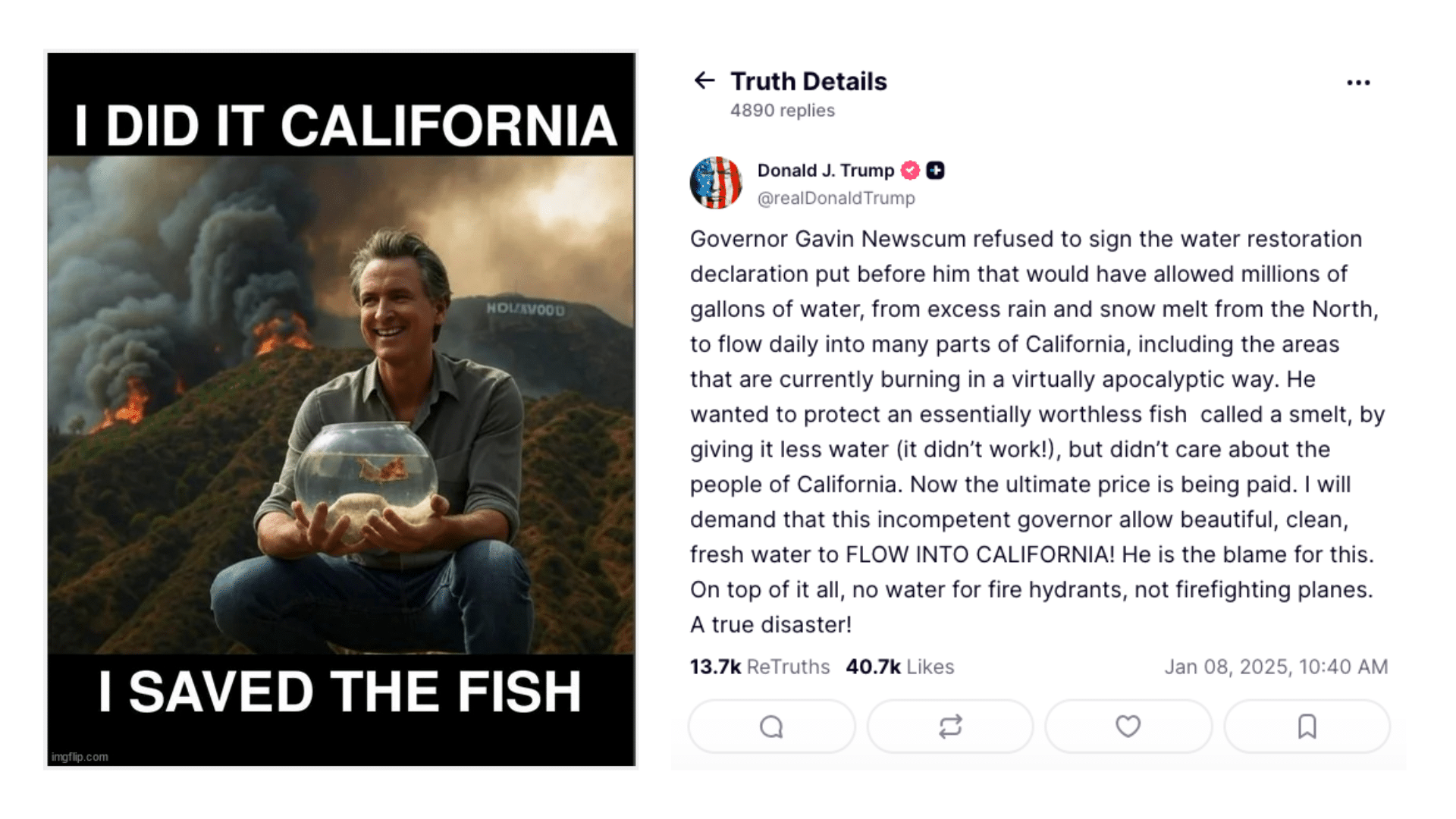

As wildfires blazed through Los Angeles, turning buildings and lives to ash, President Trump politicized the tragedy, blaming an endangered species. In a January 8 Truth Social post, Trump said—erroneously—that Governor Gavin Newsom caused the wildfires by keeping water from Southern California to save “an essentially worthless fish,” the delta smelt.

In one satirical meme, the ‘lil silvery fish says, “fuck your house.” In another, a smiling cartoon Newsom hugs a fish bowl, the charred city behind him. Trump doubled down on the rhetoric, titling a first-day memo, “Putting Fish Over People.” Besides inducing visions of Dr. Seuss characters balancing fish bowls over their heads (“This one has a little star. This one has a little car. Say! What a lot of fish there are!”) the memo disparages “radical environmentalism” while tasking the Interior Secretary with releasing more more water out of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta for specifically human use.

It turns out Donald Trump had a political score to settle. Fuck the fish. In 2020, Newsom sued the federal government, successfully, to halt a Central Valley water infrastructure project that could help farmers but harm the smelt, thereby violating the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Three inches long, smelling like cucumbers, and of little known importance, the delta smelt requires “an unprecedented level of commitment and collaboration” to save. Its existence begs the question: are species with no known utility worth saving?

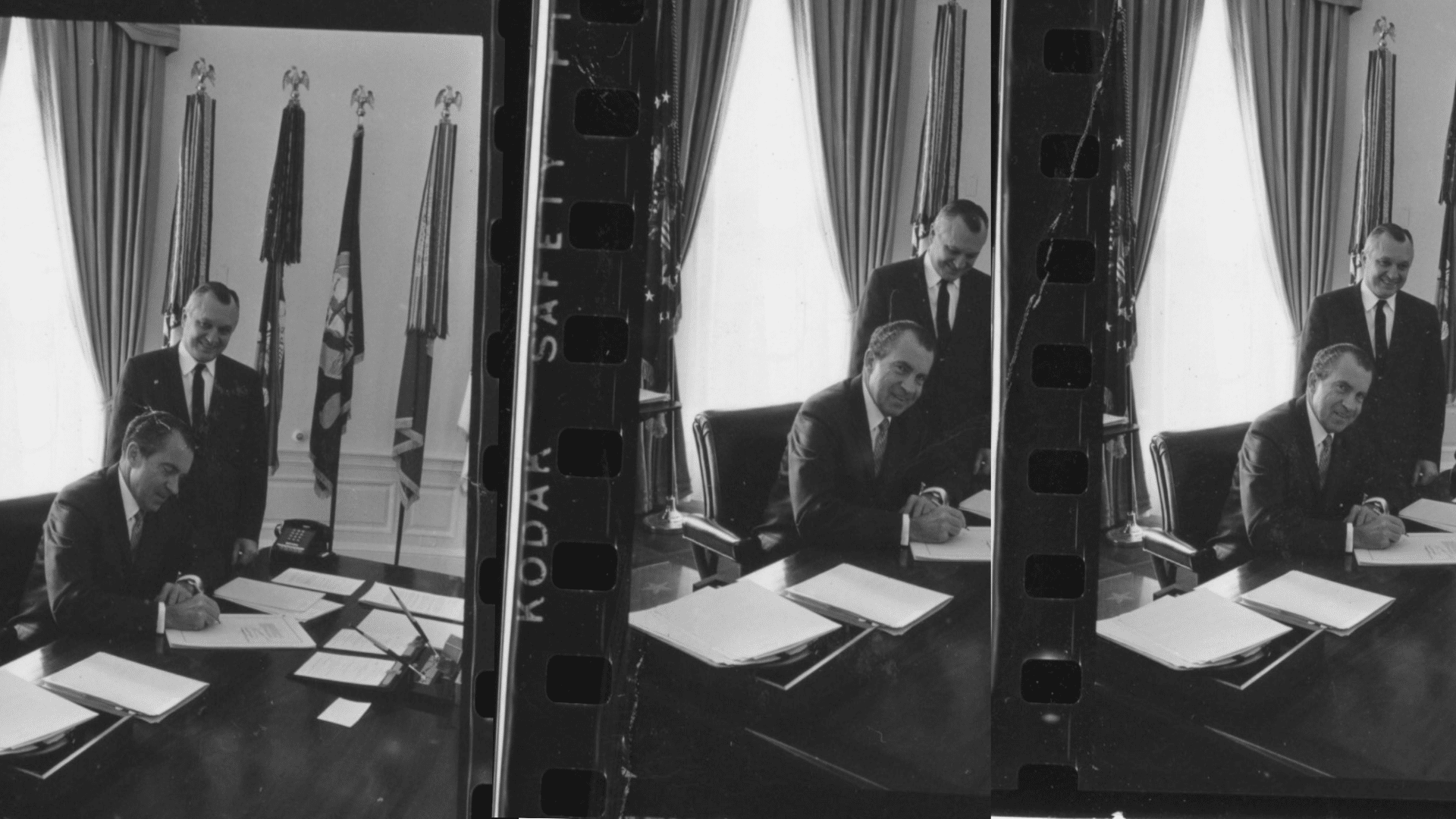

Fifty-two years ago, Republican President Richard Nixon, both houses of Congress, and presumably the American public, thought so. The bipartisan Endangered Species Act of 1973, passed 92 to 0 in the Senate and 390 to 12 in the House of Representatives.

“Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed,” Nixon wrote in his signing statement. “It is a many-faceted treasure, of value to scholars, scientists, and nature lovers alike, and it forms a vital part of the heritage we all share as Americans.”

The ESA is one of the world’s strongest laws protecting biodiversity. It covers not only fish and wildlife, but also plants, fungi, insects, and other organisms whose populations are heading towards extinction. The law requires designating “critical habitat” for each listed species. If any entity wants to build, mine, log, or otherwise change a habitat where endangered species live, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) must determine how to minimize the impact.

Yet two changes under the current Trump administration risk undoing decades of endangered species recovery. First, a proposed rule to rescind the ESA’s definition of “harm” could expose every endangered species’ habitat to development—with little or no review. Second, he resurrected the ‘God Squad,’ a committee that reviews exemptions to the Act, which should concern anyone who loves wild creatures, including the “worthless” smelt.

The threats couldn’t come at a worse time: Scientists recently found 40% of animals and 34% of plants in the U.S. are at risk of range-wide collapse (while only 1% of U.S. species are listed as threatened or endangered under the ESA). But the urgent loss of biodiversity across the globe often takes a backburner to other environmental crises, including climate change action.

“The biodiversity crisis is always the lowest priority,” John Vucetich, distinguished professor of wildlife conservation at Michigan Technological University, told Deceleration. “And when it’s always the lowest priority, you’re going to get what you expect to get, which is to lose [species]. You’re not fighting the biodiversity crisis. You’re describing the biodiversity crisis.”

Despite how frequently politicians use the ESA for rabble-rousing, mostly around specific animals (think, the northern spotted owl, wolves, or them rascally smelt), Americans overwhelmingly support the law.

“People’s support for the Endangered Species Act has been high for a long time,” cutting across sociodemographics and political views, says Vucetich, who after analyzing three decades of surveys from across the U.S., found that 84 percent of Americans support the ESA: 90% of political liberals, 82% of moderates, and 82% of conservatives; just 12% “oppose” it.

Part of the law’s popularity lies in what it protects. Humans have an innate connection to all things wild and natural, a concept known as biophilia. We feel warm and fuzzy watching videos of pandas roly-poly-ing down hills, or a black bear helping her cubs bumble across a roadway. We form intense familial bonds with our pets. We decorate with plants and nature artwork and vacation in places of natural beauty, such as national parks or turquoise beaches.

It’s not surprising that nature is health-giving. Exposure to nature in its myriad forms lowers blood pressure, decreases depression, increases focus, and hastens recovery from disease, to name a few known health benefits.

As further evidence of the bipartisan nature of protecting nature, Trump passed the Great American Outdoors Act in his first administration, mandating permanent, full funding—never before achieved—of the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) at $900 million annually, and up to $1.9 billion for the first five years, with no further need of Congressional approval. LWCF will use this for the backlog of parks maintenance and for expanding national wildlife refuges or other federal lands, which often contain endangered species habitat. Although it comes from oil and gas revenues, the Act received widespread bipartisan praise.

And a sell-off of millions of acres of public lands, which Utah’s Senator Mike Lee proposed during May’s budget reconciliation, was met with overwhelming public opposition. Not only did environmental groups take issue with it, but even conservative “hunting and angling organizations came out strongly opposed,” said Kathryn Conant, recently retired U.S. Forest Service Regional Lands Director, who worked on federal land transactions in the West. So Lee backpedaled.

Most people prefer a natural world with all of its creatures, Garden of Eden-like, to the 2805 AD desolate wasteland portrayed in the Disney film WALL-E.

In the world of policy and regulation, however, the devil is always in the details.

‘Worthless, unsightly, minute, inedible’

Soon after enactment, the ESA first showed its teeth. Environmental advocates sued the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1975 to stop the Tellico dam because its construction threatened the endangered snail darter, which the U.S. Representative from Tennessee deemed a “worthless, unsightly, minute, inedible minnow” (this seems to be a theme). But in 1978, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the fish, halting the dam midway through construction.

TVA v. Hill changed the seriousness with which everyone took the law. Any project affecting endangered and threatened species undertaken since has had to minimize harm—“take” in legal lingo, with USFWS handling terrestrial species and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) handling oceanic species.

In reality, it’s extremely rare for the ESA to completely scuttle a project. Of nearly 90,000 USFWS project consultations between 2008 to 2015, not one was halted completely or even modified to a great extent. Analyses from earlier time periods found jeopardy declared between 0.54% and 7.2% of the time. All in all, not often.

To prevent jeopardy, experts from the services work with private interests to develop Biological Opinions and Habitat Conservation Plans and the like to minimize “take” of species and “adverse habitat modification” of their critical habitat. No off-the-cuff decisions here. Such work requires intimate, detailed scientific knowledge of what each species needs to survive, reproduce, and grow in population size to the point of recovery (and with recent government reductions in force, some of that institutional knowledge just walked out the door).

While the judicial system has consistently upheld the ESA’s strength over the decades, its flexibility has grown due to bipartisan amendments (some call it “weak implementation”). Think of it as a friendly great white shark, like Bruce in Finding Nemo: he scares the bejesus out of everyone, but in reality, he’s trying to be a vegetarian.

Related: “Jaguar Watch: What ‘Finishing the Wall’ Means for Borderland Cats“

By and large, various ESA amendments have enabled positive interactions with those who may otherwise strongly resist regulations. For example, a 1982 amendment allowed the USFWS to create “experimental, non-essential” (10j) populations of endangered species on both private and federal land. Under this, philanthropist Ted Turner introduced endangered blackfooted ferrets and Mexican wolves on his ranchlands. Biologists have established such experimental 10j populations of red wolves, California condors, and whooping cranes on federal and private lands, with neighbors shielded from litigation.

Similarly, a 1999 regulatory change started ‘Safe Harbor Agreements,’ where landowners can receive financial incentives to protect or create endangered species habitat—along with guarantees they won’t be penalized if the critters don’t thrive. Under this, the private Yturria Ranch in Texas protects the biggest population of ocelots, restoring thornscrub and working with biologists to ensure success. Voluntary agreements have helped karst invertebrates and golden-cheeked warblers in the Hill Country—though a seemingly premature decision to downlist the birds may put them at risk.

All in all, these creative ways to recover species keep business interests and private landowners content—or at least not protesting in the streets. ‘Bruce’ continues acting like a nice vegetarian shark.

‘God Squad,’ Resurrected

What happened after TVA v. Hill is told less often but has direct relevance today. Frustrated by the Supreme Court’s decision, Congress amended the ESA, creating an Endangered Species Committee composed of high-level cabinet members who could evaluate case-by-case exemptions.

News media dubbed it “The God Squad” since it “has the power to say that actions that would otherwise violate the Endangered Species Act can go ahead,” Holly Doremus, University of California Berkeley Professor of Law, told Deceleration. “Congress created the God Squad as a safety relief valve… so that even [though] yes, we mostly do want to protect endangered species, in some cases, we may decide it’s not worth it.”

Yet instead of bowing to Congressional pressure, the God Squad’s first decision upheld the ESA. The fish had won—again. (The dam got built anyway. Congress added a rider to a 1979 appropriations bill, exempting the Tellico dam from the ESA. So scientists relocated the darters to other rivers, where they’ve thrived.)

The God Squad has convened just twice since—in 1979 for whooping cranes, and in 1991 for northern spotted owls. Now Trump has resurrected it.

“In one of his first-day executive orders, Trump said that he wants the Endangered Species Committee to meet quarterly and to make proposals,” said Doremus.

This was in his “National Energy Emergency” declaration, with another mention in his March order about timber production, tasking the God Squad to “submit reports” about ESA-caused obstacles.

“That’s not the way it’s ever worked… but potentially that’s a way to skirt endangered species protections,” Doremus added.

Although there’s no indication it has yet convened in 2025, it’s something to watch for.

Related: “American Stewards of Liberty: The Culture Warriors Out to Destroy ‘America the Beautiful’“

In April, the president proposed another ESA change that could put endangered species’ habitats on the chopping block. The rule rescinds the “harm” definition Congress added in 1982, when they defined “harm” as “an act which actually kills or injures fish or wildlife. Such an act may include significant habitat modification or degradation which actually kills or injures wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns, including breeding, feeding or sheltering.”

If the proposed rule, which received nearly 400,000 comments, is enacted, harm will no longer include causing habitat degradation—a move that could weaken the ESA’s effectiveness considerably—though its legality will certainly play out in the courts.

Success or Failure?

Depending on who is talking, the same stats are used to claim both the ESA’s wild success and its abject failure.

At the time of passage, the ESA listed 191 species; that has mushroomed to 1,668 species today—75 percent endangered, the rest threatened. So far, 64 species have been removed due to recovery (including American alligators, brown pelicans, Kirtland’s warbler, and bald eagles); 64 have been downlisted to merely “threatened” (Florida manatees, Louisiana black bears, and red-cockaded woodpeckers, to name a few). And in 2023, USFWS declared 21 species extinct, adding to the 11 species previously declared extinct; based on data, many of the 32 were likely extinct prior to listing. The biodiversity crisis is urgent: A 2018 report by the conservation-minded nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity states that between 150 and 650 species have already gone extinct in the U.S.—but they either weren’t listed on the ESA, such as the passenger pigeon, or scientists don’t have enough resources to declare extinction.

In March, House Committee on Natural Resources Chairman Bruce Westerman (R-Ark.) introduced a bill to reform the ESA, saying that, since only three percent of listed species have been classified as recovered and delisted, the law has “failed to achieve its intended goal.”

Environmental groups, on the other hand, flip that, saying that the ESA has kept 99% of species from extinction.

In a scientific analysis, the Center for Biological Diversity— often involved in litigation to protect species—found that the number of de-listings is “a poor measure of the success of the ESA because most species have not been protected for sufficient time…” For example, the dusky gopher frog was declared endangered in 2002; is 23 years enough time to say the ESA hasn’t worked?

“ESA has definitely been effective in preventing extinction. It has not been effective in bringing species back to where they don’t need protection—in part because of the amount of funding,” says Doremus, “and in part because [the law] doesn’t say you have to take every step necessary to bring about recovery.”

Opponents of the ESA never ask why there are so many endangered species in the first place.

And also: what would it take to recover them? “What they want to do about it is not devote more resources to recovery,” adds Doremus. “They want to redefine recovery not to mean recovery.” Many species don’t even have Recovery Plans, which the law requires; others haven’t had their plans updated, which USFWS is required to do every five years.

When the federal and state governments have expended money and effort, species usually recover. But sometimes the reason for decline is neither obvious nor easily solved. With America’s national bird, scientists knew at listing time that DDT thinned bald eagle eggshells, causing their population decline. Remove the chemical from circulation, protect habitat, and they rebounded. But for others, it’s not so simple.

We have paved over forests, grasslands, and deserts, drained wetlands, and otherwise destroyed habitats that species depend upon. Climate change is also shifting species’ habitats, or in the polar bear’s case, disappearing it. Large carnivores require massive swaths of habitat but inhospitable land often separates smaller populations from each other, including ocelots—whose Recovery Plan was sidelined by SpaceX developing a city in the middle of a long-planned thornscrub corridor. Trump’s recent appropriation of $46 billion to complete the border wall will permanently isolate critically endangered jaguar populations from each other. The REAL ID Act exempted border wall construction from the ESA because of ‘national security.’

The sheer number of endangered species reduces dollars and effort allocated for each, with sexy animals getting the lion’s share of attention. Most people don’t care about the barbed-bristle bulrush unless it’s on a developer’s land.

What You Can Do Protecting biodiversity requires all of us, and you can help. Here are a few simple ideas. Contact your Congressional representatives: Congress has the authority to block ESA-related rollbacks, and email, phone, mail, or in-person contact with representatives makes a huge difference. Stay updated: Stay up on the latest ESA-listed species, and threats to their protection, by signing up for newsletters from the organizations most active in litigation, including The Center for Biological Diversity, Earthjustice, and Defenders of Wildlife. If able, donate to them or other organizations fighting to save the ESA and endangered species. Get involved: Protection issues affecting many species and their habitats happen at the local level, including planning boards and local councils. If you care about a species or the habitat, raise awareness of that species and what can be done to help protect them.

Cost-Benefit Equations & Human Survival

While opponents like to say that protecting species under the ESA negatively impacts the economy, the law explicitly understands this, and says to do it anyway. As originally written, the ESA states, “fish, wildlife, and plants have been rendered extinct as a consequence of economic growth and [untempered] development,” and then creates a clear program to save every single species from extinction, despite that fact.

The wildlife, plants, invertebrates, fungi, and their habitats which the ESA protects, it must be pointed out, also sustain humanity. Habitats provide “ecosystem services,” such as filtering pollutants from air and water, providing the oxygen we breathe, and mitigating climate change. In traditional Native American ways of knowing, species have an inherent right to exist, independent of what they provide for us.

In 2019, Trump created a rule allowing federal agencies to include “financial considerations” when listing species and designating critical habitat rather than solely “the best scientific and commercial data available” as the law states. The 2019 rule, which also reduced protection for threatened species, was vacated by a California district court in 2022, reinstated by another court, then eliminated by Biden in 2024. Whether it will return remains unknown.

Healthy biodiversity sustains the biosphere that gives humans a toehold on planet Earth; but it also brings economic benefits that may even outweigh the costs of regulations. A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) analysis found the public placed a $13 billion value on recovering just three endangered species: leatherback turtles, and two right whale species. This comes from what people think saving those animals is worth, in addition to wildlife-watching tourism.

Studies have found that people visiting national wildlife refuges brought $3.2 billion to regional economies, and provided national parks $50.3 billion. Another analysis found that the ecosystem services from endangered species and their habitats—pollination, water and air purification, climate change mitigation, and the like— are worth $1.6 trillion.

Does Bruce Need to Change?

“The ESA is sometimes described as the pit bull of environmental law,” says Berkeley law professor Doremus (though I prefer Bruce as its mascot). Yet, she adds, “there’s never been either the political will or the funding to do really robust implementation.”

Vucetich tells a story about how Dan Ashe, USFWS Director from 2011 to 2017 under President Obama, used to say that the ESA is a glass hammer: if you wield it too vigorously, you’re going to break it. “I think it’s quite a prognostication that there would be that kind of backlash,” Vucetich says. “The concern that…some kind of political action would lead to the Endangered Species Act being, I don’t know, repealed? I don‘t think that’s going to happen. Weakened, sure, but those threats are in play all the time.”

Vucetich blames those implementing the law, particularly upsetting under past weak-willed Democratic leaders who claimed to support environmental protections. “If the director of the Fish and Wildlife Service says we’re not going to implement the most important law we have for biodiversity protection for fear of reprisal,” he argues, “you better be quite sure that that’s the case, or otherwise you’re going to be responsible for ushering in the biodiversity crisis.”

Despite the strength of the ESA on paper, keeping species from extinction takes constant vigilance from people outside of government, says Dave Parsons, former USFWS Mexican gray wolf recovery coordinator now working with the Rewilding Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to the service of “wild Nature” and frontline conservation groups. “In their wisdom, [the ESA] gave every citizen standing as a litigant to file suit against the agency to keep them on track. … That’s been the silver bullet.”

That’s exactly what members of Congress like Westerman fear, who, using language common to Trump, states that the ESA “has been warped by decades of radical environmental litigation into a weapon instead of a tool.”

Yet, the legislation’s language explicitly allows for citizen suits to keep the government in check.

“Both political parties have a history of supporting legislation that strives for clean air, clean water, safe drinking water, wildlife conservation, and protection of public land,” Conant wrote in a July Facebook post. “What saddens me the most is that we have politicized environmental conservation and wise use of our natural resources.”

Others agree. “There’s a wild disconnect between what American people think and what [the federal] government is doing,” Vucetich told Deceleration, especially considering the popularity of conservation, our love of wildlife, our desire for a healthy environment, and even of the Endangered Species Act.

The question then becomes: as this administration pushes to undermine core elements of the ESA—and roll back environmental protections more generally—will Americans across the political spectrum organize to push Congress to keep these darker instincts in check?

-30-

Deceleration graphic at top utilizes Creative Commons images generated and/or maintained by the Nixon Library, Office of Vice President JD Vance, the U.S. Forest Service, and others.