I attended ASLE—a conference held every two years by the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment—for the first time this year, presenting both as a poet and a scholar who studies rhetoric and Chicanx ecologies. Our panel served as a wonderful reunion of FlowerSong Press authors: Edward Vidaurre, editor-in-chief and co-founder of FlowerSong Press; Kamala Platt; and Marisol Cortez (executive editor of Deceleration). Our session was titled “Birds, Barrios, Borders, and Books: Chicanx Publishing and Poetics from the Belly of the Beast.”

The central aim of our panel was to collectively share insights from our ongoing creative work as FlowerSong Press authors. We sought to illuminate how poetry, at its essence, functions as a vital form of resistance in these complex and violent times. One profound question posed by Marisol during our discussions deeply resonated with me, especially as I subsequently attended another panel at ASLE that focused on eco-poetics in Latin America. Marisol’s query was whether slow, small-scale contributions, like the crafting of poetry, are truly sufficient to effect meaningful change.

I find myself without a definitive answer to this challenging question.

At this juncture, to me the act of writing feels like the most profoundly important method of engagement available. It is a crucial avenue for expression and interaction, mirroring its historical role as the fulcrum of change in countless other moments of authoritarian danger.

In this context, writing assumes a role akin to that of the matsutake mushroom, as explored by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing in The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. For Tsing, the matsutake mushroom embodies a resilient “third nature,” a phenomenon that persists and thrives despite the pervasive forces of capitalism. Similarly, writing, much like this remarkable fungus, becomes the essential fieldwork—a means to explore, to entangle with complexities, to interrupt prevailing narratives, and ultimately, “to account for the fact that anything is alive in the mess we have made.” It is through this engagement with language that we can begin to comprehend and articulate the resilience and possibilities that exist even amidst the ruins of contemporary systems.

These ideas also permeated the panel I attended, titled “Indisciplined Atmospheres of Co-Creation from Latin American Environmental Humanities,” with panelists echoing this call to view poetics as a sacred act of creation within the confines of capitalist structures.

Often, there is a palpable resistance within academic circles toward thinking about poetry in these ways.

But this resistance invites us to rethink how we create knowledge both inside the university and in the community. To truly innovate, we need a paradigm shift not only in the intellectual frameworks we use, but also in our methods for producing research and creative work.

It is in navigating these power dynamics that we can foster meaningful action and transformative change within the environmental humanities and beyond. This approach advocates a more fluid, community-connected, and ethically-grounded engagement with knowledge production, moving beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries (the “indisciplined” of the panel’s title) to embrace the transformative power of poetic thought.

For instance, Valeria Meiller, a professor of Hispanic literature and Indigenous Studies at Stony Brook University, discussed how her work as a researcher, activist, and poet is deeply rooted in understanding the profound impacts of extractivism—the practice that consumes Indigenous lands, and the minerals, plants, animals, and waters they contain, so as to compromise or even collapse entire ecosystems—both historically and presently. Meiller’s presentation emphasized the need to integrate Indigenous cosmologies (or worldviews) into environmental discourse, arguing that these diverse knowledge systems offer unique and powerful forms of resistance to ecological destruction.

As the director and co-editor of Ruge el Bosque (The Forest Howls), Meiller has published a series of intercultural and transnational anthologies that showcase the vital role of poetry in Abiayala (a Guna word that is one of the original names for the continents we know colonially as “the Americas”). This series aims to bridge cultural divides and amplify the Indigenous and Afro-descendent voices marginalized in Latin America, highlighting how plurilingual poetic expression can serve as a tool for environmental justice and cultural preservation.

In the presentation I attended, Meiller consistently pointed out the intricate connection between cosmology and language, which she said is often the least-explored aspect of how we talk about climate change. Language, she said, as an inextricable expression of a culture’s cosmology, is fundamental to how a community perceives, interacts with, and ultimately resists environmental degradation. For that reason, poetry for Meiller is the most effective medium for fostering these conversations. Along with many other poets, her presentation advocated for a broader definition of poetry, one that transcends traditional literary boundaries to encompass all ways of “naming the world.” This expanded understanding is particularly crucial in contexts where people are displaced and dying due to climate change, recognizing the many ways they articulate their experiences, losses, and resilience.

Meiller presented a quote from Emil’ Keme, a Guatemalteco K’iche’ Maya scholar and activist:

“For Abiayala to live, the Americas must die.”

This quote encapsulates a radical reimagining of the relationship between dominant Western paradigms and Indigenous ways of thinking and being. It suggests that the destructive systems embedded in “the Americas” as a colonial construct must be dismantled to allow for the flourishing of Indigenous cultures, ecologies, and cosmologies embodied by Abiayala.

Meiller uses this idea as a principle for her work in ecopoetry, underscoring the necessity of decolonizing environmental thought and practice more broadly.

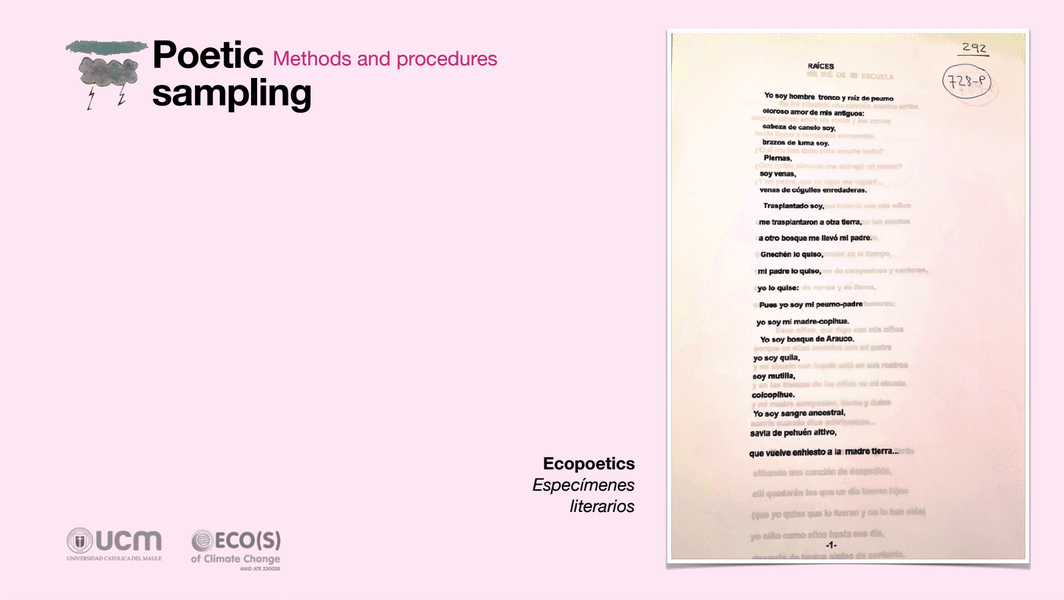

Sofía Rosa, a cli-fi writer and professor of literature at Universidad Católica del Maule, also focused her presentation on eco-poetics, in particular what she called the “unexpected archive” of “anthropoetry,” terms she used to describe ways the Earth’s own vernacular is preserved in poetry written by residents of rural Chile, who read environmental and cultural traces like a language. These “unexpected archives” serve as crucial testimonios, an ecopoetry that documents the diverse tapestry of rural memory in the face of climate change.

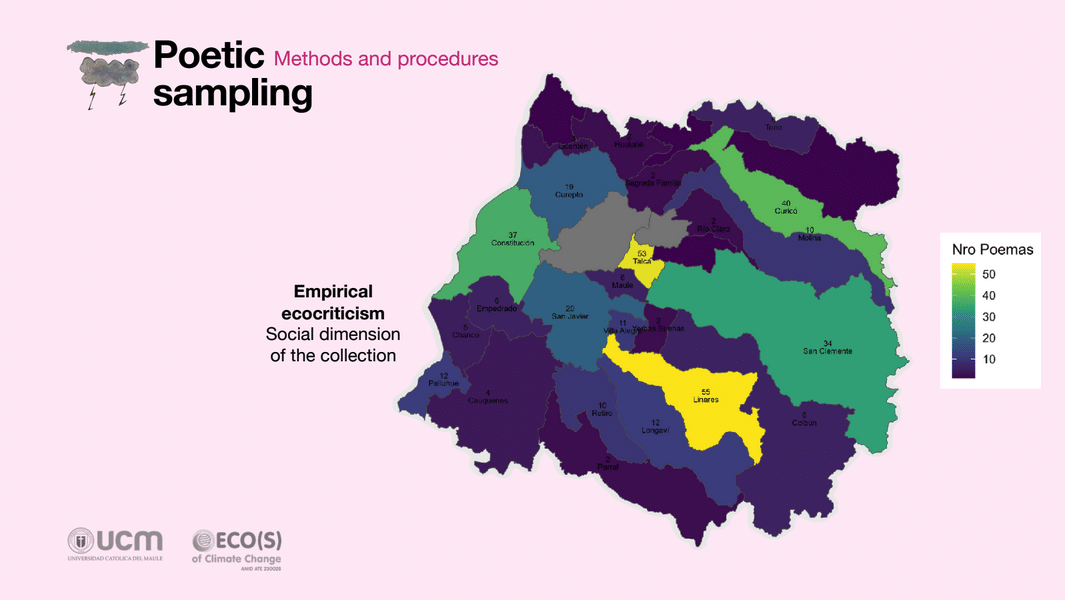

To illustrate this research, Rosa displayed a digital map. This map was not only a geographic representation of where she had gathered her anthropoetic samples, but a tool for plotting and visualizing the “poems” she collected throughout her study. Merging empirical data collection with poetic expression, she termed this methodology “empirical ecocriticism.” It offers a new lens, she said, through which we might understand and interpret the ecological narratives embedded within human and natural landscapes.

Are small-scale, poetic contributions such as these sufficient responses to the many crises we face? Even after ASLE, I haven’t found a definitive answer, though these panelists suggest it’s possible through the everyday fieldwork of poetics. Like Tsing, I lean on “third nature”—that more-than-human presence or tangible interruption that compels me to acknowledge the life within—despite the mess we’ve created. As a poet myself, we might say that poetics are that more-than-human agency that persists despite capitalism. It bridges testimonio with lo cotidiano (or the sacredness of the everyday), becoming a kind of fieldwork for excavating the conocimiento (or deep knowledge) of a place, where we constantly seek refuge and engage in a semiotic relationship with the environment.

As Meiller might say, the Earth continually asks us to reevaluate outdated concepts and learn to adapt, to listen, and to learn in the co-creation of new realities.

As Rosa notes, the language of the Earth also creates in the form of an unexpected archive. To write from where we are is to preserve this vernacular earth language—to ask for water is poetic, a question that uniquely shapes our lands. To ask for (clean) water, including the water itself, is poetry.