Water is what differentiates Corpus Christi and other coastal cities from the rest of Texas. As a city, as a congregation of people, it reflects the natural inclination by all of us to head to water, whether for survival or recreation or less quantifiable contributions found in water’s ability to soothe human nervous systems.

At the same time, water has increasingly become a point of deep divides in this “Sparkling City by the Sea.” For the last decade, water here has increasingly meant something different to those who call this city home versus those who, in some cases, simply make their money here. Water is not only the source of life; it also cools the engines of industry and offers pathways to global commerce.

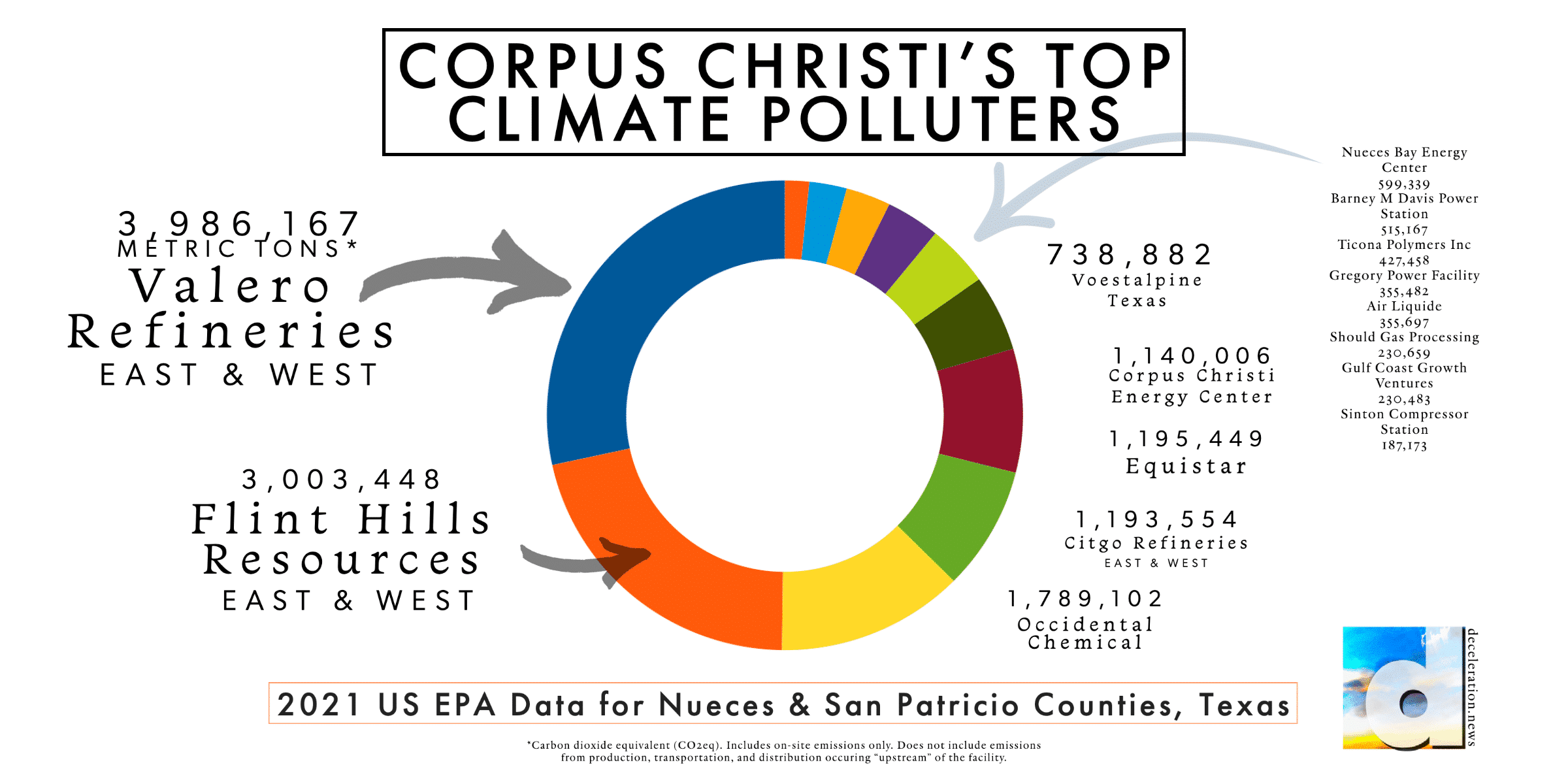

Increasingly resembling communities further upcoast in Texas and Louisiana, Corpus Christi is today inundated with high-polluting, climate change-driving industries that use incredible amounts of water to operate. Over the last decade, the city has become the largest crude export gateway in the U.S.—and third largest globally—thanks to the Obama administration in 2015 lifting a national oil export ban during fracking’s rise and the city’s concerted effort to attract industry.

Industrial water demand is what incentivized city officials in 2014 to start pursuing desalination—removing salt from high-salinity sources such as seawater via reverse osmosis—to ensure enough water for industry and over half a million area residents. Corpus Christi officials kept recruiting heavy industrial users before that proposed facility, known as the Inner Harbor Desalination Project, even reached a final design.

After selling all of the city’s water rights to the Nueces River to ExxonMobil, a steel plant, and other industries, the city banked on its desired future desal plant to fulfill future water needs.

Then the whole project seemed to fall apart last month, when a vote to fund the project’s design failed 6-3 at the conclusion of a contentious, 13-hour meeting.

Now it’s looking like industrial thirst—or their water-borne profits—are too big to fail.

On Monday, Corpus Christi officials revealed that a Houston-based wastewater agency, the Gulf Coast Authority, wants to take over the desalination project. The city will now explore this and several other water reclamation and augmentation options at an “alternative water workshop” this Friday.

The Inner Harbor Desalination Project was expected to process millions of gallons of seawater a day through a facility in the disinvested Hillcrest neighborhood, taking the water from the bay adjacent to the neighborhood. Corpus Christi markets desalination as a “drought-proof” solution for both residential and industrial water needs. The plant was expected to produce up to 36 million gallons of fresh water a day, which is more than twice the amount area residents use.

Locating the desalination plant in Hillcrest was insulting enough to people who still live in the neighborhood, along with the people who organize on its behalf. But the plant symbolized much more to local opponents of the project, including the dozens of people who lined up to speak at that September Council meeting (several of whom were arrested but later released).

For some residents, the desalination project was the City of Corpus Christi’s declaration that that the fossil fuel industry—the largest local driver of climate change, to which coastal communities like Corpus Christi are particularly susceptible—means more to them than do residents.

“I think the victory is huge because people didn’t want to touch this five years ago, because they didn’t think it was realistic,” said Isabel Araiza, a sociology professor at Del Mar College who co-founded For the Greater Good and was one of those arrested at the meeting.

“That shows the community that when we think about things as a public good and as a collective, we really do have power.”

Like San Antonio betting the future of its urban core on a new Spurs arena, the Inner Harbor project doubles down on an economic paradigm out of balance with actual human needs. Signs of this imbalance became apparent in January as the city imposed water restrictions on residents yet allowed industries to pay their way out of them, as the drought in the Nueces River, where the city gets most of its water, goes on its seventh year.

The city is currently in Stage Three water restrictions, meaning residents can’t water lawns or wash their vehicles. The city estimates it is about a year away from being in a certifiable water emergency. At this stage, the city would be within 180 days of not meeting its water demands. Only at that point can the city enforce fines on those who violate the ordinance, including local industrial facilities.

The Inner Harbor Desalination plant was supposed to come online two years ago to meet the region’s water demand. Before the city voted to stop funding the project’s design, local organizers had been fighting it for a decade. In that time, the anti-desalination movement became much bigger than just opposing industrial buildout. It was also a fight against austerity, a resistance against cutting social services, and against building new infrastructure accelerating the climate crisis. Officials and industry alike seem to have looked at the water surrounding the city and, perhaps naively, saw the solution as one being literally under their noses. But as with anything hydrological, it’s not that simple.

The brine, or salty water waste, that would be dumped in the bay (which is already too salty for some species) would likely create “dead zones” where no life could exist. West Texas A&M scientist William Rogers found “forever chemicals” in Corpus Christi’s inner harbor, the body of water where the plant is planning to pull seawater from. Rogers told KRIS 6 that there’s no evidence that reverse osmosis would remove these PFAS from seawater.

Corpus Christi’s drinking water is already contaminated with high concentrations of cancer-causing pollutants, such as trihalomethanes, according to a report by the Environmental Working Group. (In a statement on the city’s website, Corpus Christi downplayed the report, saying that the water is tested regularly and is within EPA and TCEQ guidelines.)

Paying for the Inner Harbor desalination plant was partly going to come from raising residential water rates, despite local industries using more of the city’s water than the residential sector. Regardless of Friday’s outcome, the city is raising water rates to cover the sunk costs in the project to date.

Residents speaking at the 13-hour long council meeting on September 2 weren’t convinced by any of the City’s promises for the project.

“It won’t bring us out of drought restrictions,” Joshua Fraedrick, a Corpus Christi resident and one-time candidate for mayor, told the Council during the meeting. “It’s for growth, and growth at any cost is the mindset of a virus or cancer. And here, in the body of Christ, we don’t need that cancer.” (The literal translation of Corpus Christi is “body of Christ.”)

In a statement to Deceleration, Corpus Christi Mayor Paulette Guajardo said that the city’s “growth strategy” required the city to have multiple water sources. Corpus Christi’s 20-year plan, which was published in 2016, speaks to some of this strategy. In 10 years, the municipal government wants Corpus Christi to be both economically diverse and environmentally conscious, through a host of strategies that seem counter to desalination as a whole. It also specifically calls for equity and justice for neighborhoods in the city. This does not seem to apply to what remains of Hillcrest, which went only a couple weeks without renewed possibilities of siting the Inner Harbor project there.

Though the city is still pursuing other water projects, including groundwater siphoning and nearly doubling the water it takes from Lake Texana, Guajardo said that Corpus Christi is still “working to move forward” with desalination and that the city’s water future depends upon all members of the community working together. When asked for comment, Flint Hills Resources (FHR), which operates two oil refineries in Corpus Christi, said in a statement that the city needed reliable water supply for area industry operations.

“This is a challenge that requires leadership and all of us coming together to do our part to help conserve water and advance practical long-term solutions,” FHR’s Vice President of Public Affairs Jake Reint told Deceleration.

Sylvia Campos, Corpus Christi’s District 2 councilwoman and a member of For The Greater Good, echoed these sentiments after voting with five other members to not fund the design of the desalination project. She said she hoped the vote would bring all the community stakeholders together to start charting a more just and sustainable course forward.

“It’s too soon to tell, but I’m hoping that this will be the catalyst,” Campos said. “Until we are able to come and sit down and actually have a meeting and have actual representation from the community, I’m still on the fence. I want it to happen, but I don’t see anything concrete yet.”

Corpus Christi spent $50 million designing the desalination plant and had over $200 million more in state loans reserved. Since Council rejection of the design funding, the City is now asking the state if it can use the money for other water projects. In August, Corpus Christi approved a groundwater contract to extract groundwater from the Evangeline Aquifer northwest of the city. Despite this, Moody’s Ratings are now reviewing Corpus Christi’s bond rating for potential down-ranking, which could jeopardize the city’s ability to borrow money for future projects.

But all of these water projects are a reflection of a city’s insistence on engineering their way out of a dwindling resource. Mining groundwater is like using fossil fuels to extract more fossil fuels. To search for any other solution than regulating industrial water usage, establishing a culture of conservation, and measuring progress in terms of water quality as much as quantity, is unequivocally to miss the point.

This Friday’s meeting will be the edge of the catalyst, what determines not only Corpus Christi’s future direction, but also whether a community will have to endure another decade of convincing the city of water’s sole truth.