When Donald Trump and Kamala Harris faced off for their first—and likely only—debate before the November election, they offered next to no reflection on the climate crisis. A habitable planet just hasn’t become a top-shelf concern for most voters even as land and sea temperatures hurtle headlong into unprecedentedly hot territory thanks to the continued accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, primarily caused by the burning of fossil fuels.

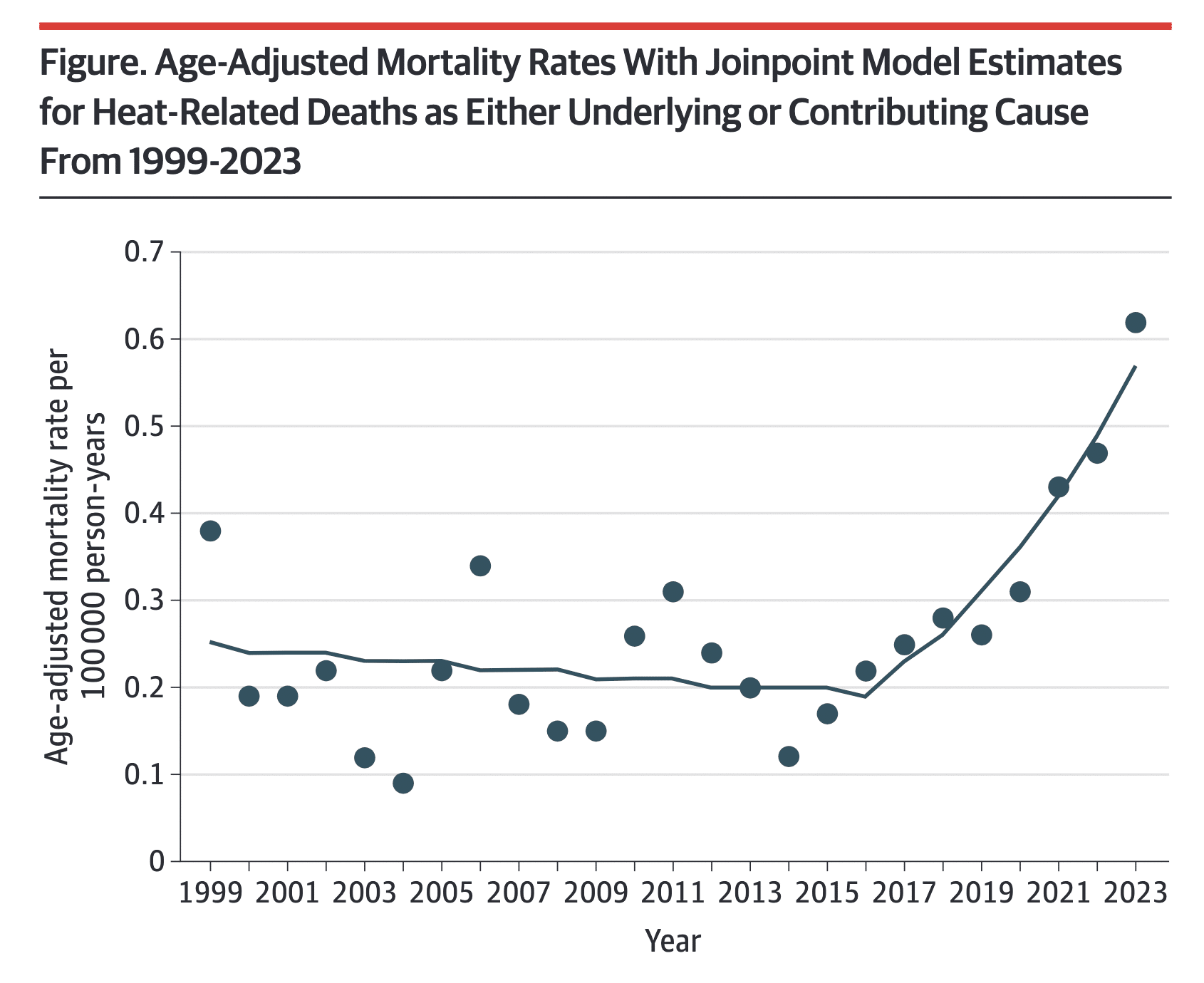

Increasingly, the cost of our fossil fuel dependence is showing up in city and county morgues. Recent research suggests that there has been a 117 percent rise in heat-related deaths in the United States since 1999, most noticeably since 2020, as the Earth returns to sweltering temps that likely haven’t been seen in more than 125,000 years.

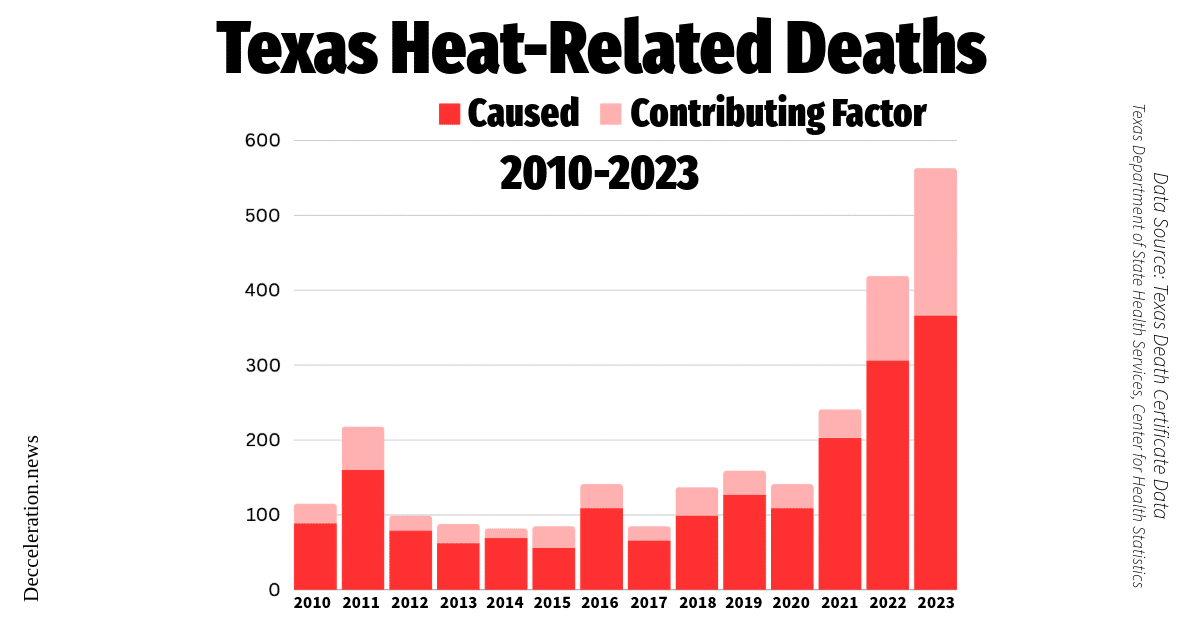

Here in the United States’ most prolific oil and gas-producing state, a whopping 563 heat-related deaths were recorded last year, according to state data released to Deceleration by open-records request.

Similar to national-level findings, heat deaths in Texas have grown most dramatically over the last three years. In 2022, for instance, there were 419 heat-related deaths in the state. There were 241 the year before that. In 2020, 141 residents succumbed to the heat. This is all the more remarkable considering that heat-related deaths over the previous decade averaged about 124 per year, according to Deceleration’s analysis of state data.

“I think a lot of people are on the cusp of having an ‘Oh shit’ moment about extreme heat,” Texas A&M University climate scientist Andrew Dessler wrote Deceleration. “Hotter temperatures do not mean tank tops and grilling in the backyard. It means, at best, changing how we live. At worst, it means suffering and death.”

Several of these numbers are significantly higher than most previous reports. In January, the Texas Tribune, for example, reported 334 heat-related deaths in the state in 2023. According to the most recent data, heat was the primary cause of death in 366 of last year’s 563 heat-related deaths; the remaining 197 deaths involved extreme heat as a contributing cause of death.

It’s too early in the year to know how 2024 mortality figures will shape up. While global heat has continued to rise virtually unabated, and 2024 is almost certain to replace 2023 as our hottest year ever recorded, Texas’s summer temps eased off a smidge—and are likely to “only” rank around our fourth or fifth hottest.

However, painful losses continued to accumulate. Last month, 46-year-old Jessica Witzel died on a sidewalk in the Five Points area of San Antonio, an apparent victim of both the urban heat island effect that focuses heat disproportionately toward more severely denuded urban areas, and the failures of local networks of care that are supposed to help those in crisis.

This year, the San Antonio Metropolitan Health District stopped publicly reporting heat deaths after more than a decade of attempting to include them alongside cases of heat illness and heat stroke. Over the last decade, Metro Health has only reported one heat-related death. Report after report published only “N/A,” not available, for the category. However, in April of this year, Deceleration uncovered at least 28 heat deaths in Bexar County since 2019.

Deceleration reached out to a handful of City Council members about the state of local heat-busting efforts. Councilmember John Courage released a statement to Deceleration that included recognition of the extremes hitting local communities. Last year, he said, was “extraordinary” for its intense temperatures and resulting heat illnesses and deaths.

“As our city continues to experience rising temperatures due to climate change, the safety and well-being of San Antonio residents remain a top priority,” Courage wrote, before highlighting current public heat education efforts and the expansion of cooling centers across the city.

“We are continuously working to integrate heat emergency preparedness into San Antonio’s long-term planning, helping us build a more resilient city in the face of future extreme weather events.”

A spokesperson for the Texas Department of State Health Services said that they were aware of dozens of deaths collected from across the state during June and July. They cautioned, however, that it can take many weeks before death certificates reach the state. Likely it won’t be until November or December that anything resembling a complete accounting of 2024’s summer will be available.

In April, Deceleration reported that there had been 357 heat-related deaths in Texas in 2023. However, this figure fails to include cases where heat was determined to be a contributing cause of death. Heat-related death data in Texas is divided between primary causes of death and contributing causes of death, as recorded in death certificates signed off on by an attending physician, medical examiner, or Justice of the Peace.

The distinctions matter, yet both are critical to understanding heat’s full impact on public health. Deceleration’s charts today are the first, to our awareness, that contain a full accounting of heat-related deaths in Texas since 2010 that are maintained by the state.

Definitions

Primary Cause of Death

Method One (M1): Counts for deaths where X30 (hyperthermia) was indicated as the underlying (immediate) cause of death.

Contributing Causes of Death

Method Two (M2): Counts for deaths where ICD-10 Codes X30 (exposure to excessive natural heat), P81.0 (environmental hyperthermia of newborn), or T67 (effects of heat and light) are listed as the underlying (immediate) cause of death, or as one of the contributing causes of death.

Method Two excludes deaths marked as being caused by exposure to excessive heat of “man-made origin.”

It is critical to include both methodologies when reporting on heat deaths, said Christina VandePol, a Pennsylvania physician and former coroner who speaks frequently on the hazards of heat.

“Many ‘excess deaths’ during a heat wave occur because people with underlying medical conditions are more sensitive to heat than otherwise healthy individuals,” VandePol told Deceleration. “In other words, but for that heat stress, they might not have died.”

“Without counting M2 deaths, we don’t have a full picture of the human harm caused by hotter temperatures,” VandePol said. “Without that full picture, we don’t know there’s a problem and can’t find solutions needed to save lives.”

Deceleration has been highlighting failures in local heat accounting to suggest wider failures in understanding heat-related deaths in Texas. In October of 2023, for instance, we wrote about how lack of reliable data was hobbling efforts in Bexar County, where the medical examiner has said repeatedly (through two different media liaisons) that they do not track heat deaths. Last year, the National Association of Medical Examiners issued a policy paper urging medical examiners to document disaster-related deaths, including heat waves and hyperthermia.

In April, we highlighted Nueces County, where the operations manager for the Nueces County Medical Examiner’s Office told Deceleration that heat deaths are rarely recorded by his office due to insufficient local surveillance efforts.

Last month, reporters from the Texas Tribune and Inside Climate News collaborated to investigate if and how local and state government are underestimating heat’s deadly impact. The team highlighted cases from around the state, spotlighting Bexar County and noting Nueces. In that effort, the team included both Method 1 and Method 2 deaths in their accounting, stating that “[s]tate records report that 365 people died directly from heat, the most heat-caused deaths on record. The count rises to 562 when including deaths where heat was a contributing cause.”

For 2022, the Tribune previously reported that “at least 279 heat-related deaths were recorded last year, the highest annual toll for the state since at least 1999, according to data from the Texas Department of State Health Services.”

But Texas saw 419 heat-related deaths in 2022, according to the most recent data available. There were 306 deaths where heat played a primary role, and another 113 deaths where heat was listed as a contributing factor, according to state data provided to Deceleration.

See: Raw Data as of 09/04/2024 via Deceleration Open Records Request of Texas Department of State Health Services, Center for Health Statistics

Experts across various sectors are on the record that heat deaths are being undercounted, including in the workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, only now developing what could be the first national standard for preventing health-related workplace injuries after decades of pressure, recently described workplace heat deaths as likely a “vast” undercount.

A Research Letter published late last month in the Journal of American Medical Association (and kindly passed to Deceleration from a contributing writer at Yale Climate Connections) found that annual heat-related deaths in the United States rose from 1,069 in 1999 to 2,325 in 2023—a 117 percent increase. The rise has been the most dramatic since 2020. The team, including a lead author based at University of Texas at San Antonio, concludes that it is also a trend unlikely to subside any time soon.

“As temperatures continue to rise because of climate change, the recent increasing trend is likely to continue,” the team write. “Local authorities in high-risk areas should consider investing in the expansion of access to hydration centers and public cooling centers or other buildings with air conditioning.”

Lead author Jeffrey Howard, an associate professor at UTSA’s Department of Public Health, said that even the team’s high numbers are still almost certainly an undercount as previous studies have repeatedly demonstrated more excess deaths during severe heat waves than are officially accounted for on death certificates as heat-related deaths.

There are also issues with training and lack of basic medical knowledge about each person who has died.

“There are always going to be some number of deaths that were set in motion by excessive heat exposure, but it is just not known and the person filling out the death certificate does not list it because they are not aware of those details,” Howard wrote Deceleration.

Consider also that there are only about a dozen medical examiners operating across Texas, mostly in the large cities, and sometimes serving multiple counties. In much of the state, it is justices of the peace (who aren’t typically medical professionals) marking down causes of death. But even attending physicians may also fail to recognize or report heat’s human toll, VandePol told Deceleration.

In July, VandePol wrote that in spite of recent guidance to document heat deaths, chronic underreporting continues by coroners and medical examiners.

“Physicians in the community may fail to recognize heat as a contributing factor when someone dies of a heart attack, stroke, or kidney failure. Even when physicians suspect heat exposure, they may not be aware they must report such deaths.”

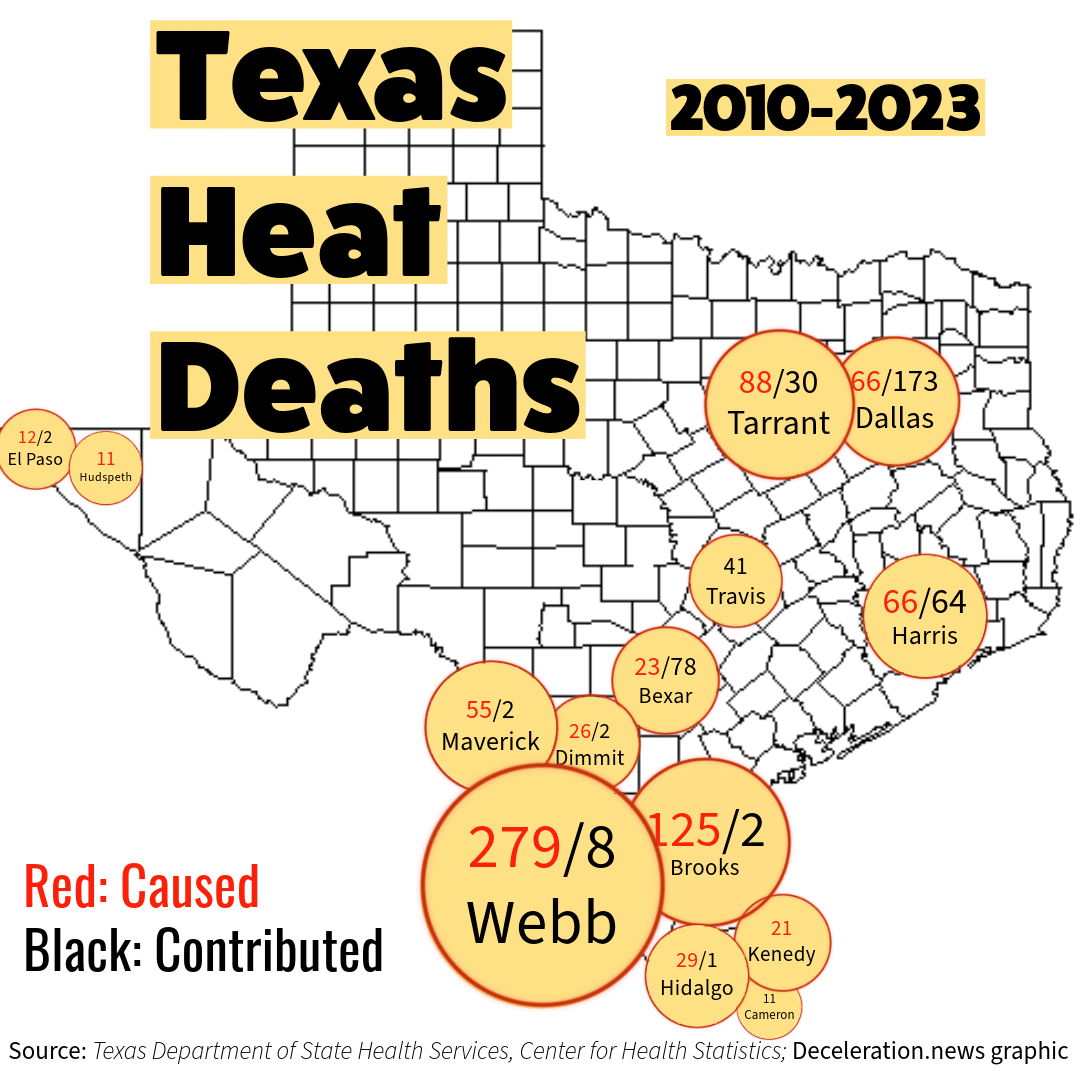

To fully appreciate how heat-related deaths are impacting the state requires also considering where people are dying from heat being caused by global energy decisions.

After reviewing Deceleration’s heat death maps, Dessler noted the large number of heat deaths that have congregated in and around the Rio Grande Valley.

“That’s a very poor part of Texas, so it clearly shows how the poor will bear the brunt of the suffering,” Dessler said. “When rich people say ‘we’ll adapt,’ they mean they’ll adapt and the poor will suffer and die.”

12 Heat-Related Deaths in Bexar County Last Year?

The Slow, Winding Road to Understanding Heat Surveillance

It was Albert Garcia—who lost his feet and part of a leg during 2021’s Winter Storm and later died on the streets of San Antoniuo while living unsheltered during the city’s hottest summer on record—that prompted Deceleration to deepen its reporting efforts around heat-related deaths. However, getting reliable information from Bexar County, where the Office of the Medical Examiner is supposed to lead such tracking, has not been straightforward.

This is a timeline of those efforts.

- September 2023: Deceleration requests Albert Garcia’s autopsy and related records. The request is rejected by Bexar County officials, who claim there are “no records responsive to your request.”

- September 15, 2023: Now former Bexar County Public Information Officer Tom Peine tells Deceleration the Bexar County Medical Examiner does not track heat deaths.

“The Medical Examiner does not track hyperthermia as a death category as that would present particular challenges. All data that is being tracked is based on scientific method and facts. While hyperthermia may be documented as a contributing factor in the autopsy report, it is not available a separate datapoint.”

- September 18, 2023: When asked for a clarification, Peine writes that the ME may in some circumstances report heat deaths under M2 (as a contributing factor) but never under M1 (as a primary cause of death).

“After speaking to staff at the Medical Examiner’s Office, I can reassure you that my initial statement dated Friday, September 15, 2023, still stands. ‘While hyperthermia may be documented as a contributing factor in the autopsy report, it is not available a separate datapoint.’”

- February 2024: Deceleration’s appeal to the Texas Attorney General’s Office for records related to Garcia’s death prompts Bexar County to release Garcia’s autopsy, a toxicology report, and several pages of case notes. The documents highlight the high heat at Garcia’s camp and inside his body hours after his death, including a 2 a.m. measurement of 94.4F at the campsite and a core body temperature reading of 92.1F.

- February 20, 2024: Referencing these high heat readings and the ME’s decision to classify Garcia’s death as a drug overdose, Deceleration writes the Bexar County Public Information Officer again. PIO Monica Ramos responds: “Tom [Peine]’s response still stands” as to the ME’s practice of not tracking heat deaths. As to heat as a possible contributing cause of death in the case:

“If the autopsy report and the cause and manner sheet does not list contributing causes, then there are no contributing causes.”

- April 2024: Deceleration hosts a Heat Emergency community forum and launches a ‘Count the Bodies!‘ petition intended to bring reforms in local heat surveillance.

- April 12, 2024: A Deceleration open records request with the Texas Department of Health and Human Services reveals 28 people have died from the heat in Bexar County between 2019 and 2023. This is 27 deaths more than San Antonio’s Metro Health has reported as part of its heat surveillance.

- August 12, 2024: Ramos supplies the Texas Tribune/Inside Climate News team with a count of heat-related deaths in Bexar County. It lists 28 heat-related deaths in Bexar County since 2019.

- August 14, 2024: The Texas Tribune/Inside Climate News team publishes the story “Texas likely undercounting heat-related deaths” that includes some of the data supplied by Ramos, including the fact that Bexar County saw 12 heat-related deaths in 2023—or “five times the annual average for the 10 prior years,” as the Tribune/ICN reporting team writes.

Deceleration asks Ramos to forward the heat death data that she provided to ICN/Texas Tribune.

Ramos does not respond to our email.

- August 16, 2024: Deceleration emails Ramos a public information request for “all communications on the subject of heat deaths, heat-related deaths, and hyperthermia in Bexar County since January 1, 2024 originating with or delivered to Monica Ramos, Public Information Officer for Bexar County.”

Ramos does not respond to our email.

- August 19, 2024: After a follow-up email from Deceleration, Ramos agrees to process the open-records request. She says that the Tribune team “mischaracterized” the data she supplied. She insists again that Bexar County “does not track heat-related deaths.”

Ramos writes:

“The County does note when a death is due to heat, but not when a death is heat-related. The County does not track deaths when heat is a contributing factor. Please refer to Tom Peine’s email to you in October 2023 and referenced by you in an email message to me on February 20, 2024.”

In other words, the Medical Examiner in some cases may report a death under M1 (as a primary cause of death) but never under M2 (as a contributing factor). This is the exact opposite of what both Peine and Ramos have repeatedly claimed over the previous year as ME policy (see September 15 and 18 above).

- Aug. 19, 2024: Deceleration writes again for the source of the dataset provided to the Tribune/ICN showing 12 heat deaths in Bexar County last year.

Ramos does not respond to our email.

- September 10, 2024: In response to our public records request, Bexar County supplies Deceleration copies of Ramos’s communications on heat-related deaths. In spite of the coordination required with the Office of the Medical Examiner to answer the questions from the Texas Tribune/ICN team, all of the communications provided are between Ramos and the Texas Tribune.

Her response to the Texas Tribune includes this:

Thanks for reaching out. I apologize for the confusion. Bexar County does track deaths from hyperthermia but not heat related deaths. As I mentioned previously, if someone were to pass away from a heart attack or stroke, then the record will reflect that the individual’s cause of death is a heart attack. The record does not necessarily denote that the death is heat related.

“If someone were to die from a heatstroke,” she continues, “then the record would reflect hyperthermia as the cause of death. This is not considered a heat related death. Hyperthermia is considered the cause, not a related cause of death.”

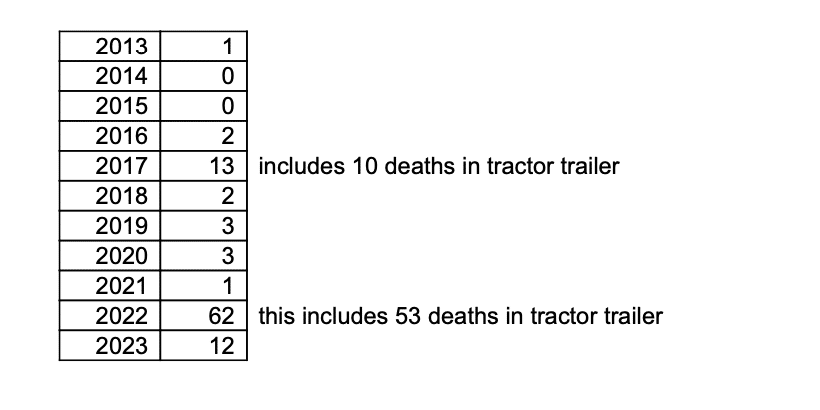

Below is some statistics from Bexar County including note of the 2017 and 2022 migrant deaths inside tractor trailers.

- September 11, 2024: Deceleration writes again for the source of the data supplied to Texas Tribune/ICN and for clarification concerning the 180-degree reversal of heat-tracking practices at the ME’s office.

Ramos has not responded.