In the state of Texas, private property is king. But every once in a while even an enthroned interest gets deposed. For years, Lennar's plans for nearly 3,000 homes just upgradient of major aquifer recharge features has been subjected to a bruising string of rejections and local opposition.

Yet with a challenged permit in hand for the wastewater treatment plant from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, it’s still possible Florida-based Lennar’s requested funding mechanism for its efforts in Northwest Bexar County may still secure state support—in spite of widespread negative local sentiment.

On Jan. 16, members of the San Antonio Planning & Zoning Commission heard Lennar's pitch for the creation of a municipal utility district (or MUD) to allow them to pass the cost of wastewater and other services onto future homeowners.

“The only science showing what this development would do was a comprehensive hydrological study by Southwest Research Institute funded by the city,” Steve Lee, a prominent project opponent, told commissioners.

“It concluded that additional wastewater systems from residential development in the Helotes Creek watershed would ‘significantly degrade the watershed and the quality of water recharging the Edwards aquifer.’ A municipal utility district for Guajolote Ranch would practically assure that this would happen.”

Commissioners recommended 5-4 that City Council not support the application.

A hearing by Council this Thursday before a planned February 5 vote exposed deep concerns among members, in spite of improvements negotiated by San Antonio Water System (SAWS) staff including a pledge to utilize advanced nutrient removal at the wastewater plant.

The potential risk is not just local water wells, which will certainly see the pulse of treated effluent in the upper Trinity Aquifer first. But underground connections to the wider Edwards Aquifer puts at risk the primary drinking water source for 1.7M people across the greater San Antonio region.

Donovan Burton, senior VP over water resources & governmental relations at SAWS, told Council members: “We believe a lot of the significant concerns have been mitigated, as it relates to SAWS' water source, in terms of the Edwards Aquifer.”

That take is still disputed by many fighting the project. And Burton reminded Council that he was not disputing more localized impacts to the Trinity Aquifer and local water wells.

Images from the January 16, 2026, Planning Commission meeting. Testimony by residents available on Deceleration's YouTube channel. Images: Greg Harman

It became clear in discussion that Council doesn’t have power to start or stop the project—or the wastewater treatment plant permitted to discharge a million gallons of treated wastewater per day (including contaminants like so-called “forever chemicals” that wastewater plant’s don’t clean up).

A trio of commissioners at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, approved a wastewater permit last October, against the concerns of their own in-house Office of Public Interest Counsel.

The larger question now may be if state appointed leaders even care what local elected officials—and the people who elect them—think.

After all, as members of the Scenic Loop-Helotes Creek Alliance have meticulously documented:

- All of the state reps from the area objected to the wastewater plant.

- State Sens. Roland Gutierrez, Jose Menendez, and Sarah Eckhardt also all warned of the threat of the treatment plant.

- After approval of the wastewater permit, Bexar County Commissioners petitioned the TCEQ to reconsider.

When Council votes on February 5 they can consent to the creation of the MUD, deny the application, or take no action. But even outright denial starts a clock on potential negotiations with SAWS that ultimately lands before the TCEQ. And while the project will be embarrassing shade of black and blue from local resistance, that’s unlikely to prevent approval by appointees who owe their station to Governor Greg Abbott.

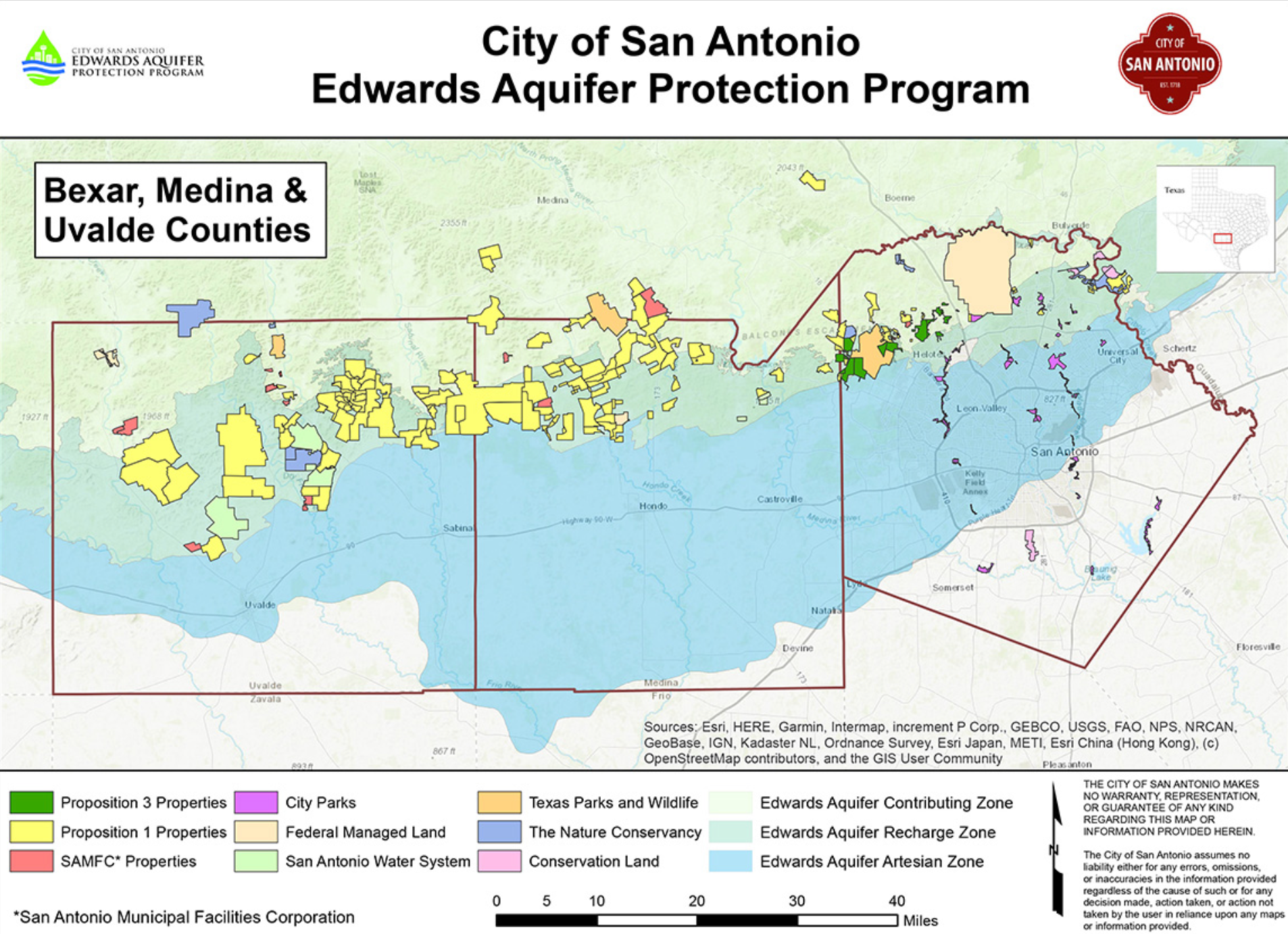

The near universal loathing for the project, however, speaks to the sensitivity of the location. The City of San Antonio has spent hundreds of millions buying up land and entering into protective conservation agreements with landowners west of San Antonio to prevent exactly this sort of feared contamination through the Edwards Aquifer's recharge and contributing zones.

San Antonio’s current city council has been described as the “most progressive” in the city’s history. Several members grew into elected office after first rooting themselves in community activism and organizing, including with organizations like the Democratic Socialists of America. But the council has strong neoliberal moorings, too, and a sturdy right flank representing a largely older, whiter, and more politically conservative demographic to the north.

Most recently, Marc Whyte (D10) and Misty Spears (D9) sought to distinguish themselves from their center and left-of-center colleagues by posing for pictures with a local ICE official. This photo op came as the agency is being widely disparaged for its chronic and wanton abuses of the people of Minneapolis, including killing protesters, and a rising detention death count. It was an intended signal preceding a public hearing on the city’s relationship with ICE that was attended by overflow crowds, many demanded the city stop cooperating with the agency.

So when a controversy over private property development—property outside the city limits—reached the group, a divergence of opinions was to be expected. But apparently every once in a while a project so egregious that even the right flank folds.

“I really do believe in private property rights, but I have a lot of concerns about a MUD,” said Spears. “It creates a separate government with its own permanent tax rate. That tax layer sits on top of city, county, and school district taxes and lasts indefinitely.”

She also claimed allegiance to water.

“I also represent a district that’s over the recharge zone,” said Spears. “It is the true gold of the state. So we really need to pay attention to the water.”

Amy Hardberger was a SAWS board member when Lennar made its original petition for Guajolote water and sewer service years ago.

She said the fact that developers are approaching utilities like SAWS before interfacing with local elected leadership signals an unhealthy political system.

“I think SAWS did the very best that it could [on Guajolote] and did more than it would have done on a similar project 10 or 15 years ago,” said Hardberger, who today is a professor of water law and director of the Center for Water Law and Policy at Texas Tech University.

“I think the question that needs to be asked is why is a municipal water authority essentially the gatekeeper for development? Is that really the way we want this to go? Because what ends up happening is oftentimes, [developers] come to SAWS first because they're not going to have any city council approval.”

Councilmember Ivalis Meza Gonzalez (D8) lamented the lack of “meaningful local control” that would have helped avoid the situation to begin with.

“I will not be supportive of this on February 5 and I ask my colleagues to do the same,” she said, adding that more changes are needed to avoid future cases like Guajolote.

She called for a review the Edwards Aquifer Protection Program and what properties are being prioritized for purchase and conservation agreement saying:

“I do believe we are able to achieve more priorities for the public by conserving properties within Bexar County that are more likely to be developed in the very near future."

UPDATE (Jan. 26, 2026): The San Antonio-based nonprofit Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance sued the TCEQ over its permitting of Guajolote's proposed wastewater treatment plant, alleging that "Municipal Operations’ Application is the product of numerous errors and must be reversed."

Related Video

What is the Environmental Impact of 3,000 Homes? Deceleration Video