Editor’s Note: Jessica Witzel’s medical autopsy tells an institutional lie. It is a sleight of hand that effects a kind of double erasure. In failing to accurately codify and count heat-related deaths, local government invisibilizes the disproportionate impact of climate crisis on the sickest and poorest—unhoused people, especially those with serious mental illness or who use substances, especially methamphetamines. In the process, the state also makes invisible its own responsibility to prevent such deaths, displacing it instead onto the dead—individualizing those deaths as accidents, making them less socially grievable by marking them publicly as overdoses. They did it to themselves. What can you do? They didn’t want help. But these are public deaths with public health and policy solutions.

If you missed those critical updates on Witzel’s death, I encourage you to start there (See: “Her Body Was 126 Degrees After She Died; Bexar County Medical Examiner Blames Drugs”).

For this story, I want to reflect on some of the ways these dynamics played out on a much smaller and more intimate scale—the neighborhood—building on Witzel’s medical postmortem with a kind of social autopsy, as sociologist Eric Klinenberg described his analysis of the 1995 Chicago heat wave. Pieced together slowly over many months through reader messages and public records, what emerges is an understanding of our neighborhoods as contested terrains, sites for competing imaginings of community—of who does and doesn’t count as a neighbor, and by extension who does and doesn’t deserve to be safe. In one understanding, neighbors band together to punch down, dehumanizing the unhoused so as to more easily remove them from the world of the propertied and able-bodied. But the neighborhood is likewise the site of many small acts of care that hold out other possibilities—that residents might band together instead to punch up, demanding real options for meeting all neighbors’ “true level of need,” in the words of advocate Sonja Burns. — Marisol Cortez

‘If They Had Helped Her That Day, She Would Be Alive’

Two days after first publishing Witzel’s story, someone whose name I didn’t recognize friend requested me on Facebook. I ignored it.

Then I got a direct message from the same name: Mikhail Timofeyev, Mischka for short. He saw Witzel the day before she died, he told me. Timofeyev is the owner of the Web House Cafe and Bar, just north of where Fredericksburg Road hits Blanco. I know the place, drive by it regularly, though I’d never been inside. Or had I, decades ago? Didn’t it used to be an internet cafe?

Could I meet up with him? I asked Timofeyev. He agreed, advising me to drop by while he was working: he was there every day from 6 p.m. till 2 a.m, he said.

Timofeyev was cooking the following evening when we arrived, but between orders he joined us at the table, bringing water for me and cold sodas for the kids. The Web House had never been an internet cafe, he said; since 2006 it had been a neighborhood eatery and hang out, with a pool table and digital jukebox and small stage for live music and karaoke. Before that, it had been a 24-hour taco place where people would come after partying on the St. Mary’s Strip.

Today it also offers a community pantry just inside the front door, a commercial kitchen shelf piled with canned goods and dried beans. On the other side of the entrance is a contribution box for the Beacon Hill Area Neighborhood Association. On the flatscreen TV behind the bar, rotating slides announce that Web House also offers notary services(!) and shares hours for the community pantry. Walk ins okay, the screen says; call Mischka for more information.

It makes sense: Timofeyev is community-minded. It was while serving as vice president of the Beacon Hill Neighborhood Association, he told me at the table, that he first encountered Witzel. Once, a few years back, she’d come in to ask him to intervene with a guy who’d been harassing her. From the way she spoke he could tell she was ill—but she never came back after that. She never came in to use the pantry. He’d see her around the neighborhood, though.

On August 21, the day before Wizel died, Timofeyev saw her around 1 p.m., he said. She was at the Valero on Woodlawn and Fredericksburg Road, entering the store with two large cups. For water, he assumed.

Later, he would share video captured just before 6am that morning by security cameras at the Webhouse, of Witzel selecting a broom from her shopping cart and sweeping the sidewalk and parking lot in front of Timofeyev’s building.

In the video it’s still dark out, but Jess is wearing shades. Hair cropped, she’s dressed in an oversized blue-and-black checkered shirt over shorts and black-and-white Adidases. Earrings jump and dance as she sweeps. Even unhoused, she looks stylish as ever. When she finishes, she picks up a crumpled can from the lot, then stands back a moment to consider her work, crossing one leg over the other as if satisfied.

Witzel was not unknown to the neighborhood, nor her escalating mental health struggles. She had lived in Beacon Hills for years and frequently returned when not hospitalized or incarcerated, where neighbors would call SAPD to report her for trespassing at her then-vacant house. Her final arrest on June 13, according to statements from neighbors included in communications between Witzel’s family and County officials, came about after a group of neighbors banded together when a delusional Witzel wandered into people’s yards taking random items and piling them into a rolling orange dumpster.

Court records show that she served 44 days in Bexar County jail for taking “FIFTY-THREE (53) Pins and ONE (1) Cast Iron box” from a neighbor, “with a value of $100 or more but less than $750.”

So when Timofeyev saw Witzel at Valero the day before she died, he gave neighbors a heads up. Then he called 911 and asked if they could send someone. Then he left.

Timofeyev knew about Jessica’s history with the neighborhood, knew police were looking for her. But he also knew—here he’d waved something away with one hand, hunting for the right words—they were looking for her “more just to get her help,” he said.

Ten or 15 minutes later, Timofeyev went back to Valero. He parked on the side of the store where Witzel couldn’t see him and just watched her for a while. She had a shopping cart, the two Big Gulps of water, a teddy bear. She appeared shaky, he said. Jumpy.

He sat there another 10 or 15 minutes. By the time he left, about 40 minutes had lapsed since he’d called 911; in that time, no one had shown up. The SAPD incident report generated from that call shows an officer was dispatched and arrived at 2:01 p.m., only to leave again at 2:14 p.m. without filing a report. It provides no explanation why, nor does it indicate what happened once officers were on scene or whether they encountered Witzel.

Witzel’s autopsy report would fill in some of these gaps, noting that officers located her less than an hour later, around 3pm—when a neighbor discovered her trying to drink water from an outdoor faucet on their property and called SAPD. She’d been sick, she told them, something confirmed by medical records later obtained by the Bexar County Medical Examiner, which show she’d visited urgent care the day before for “fever, sore throat, difficulty swallowing.” Later, death scene investigators would find an antibiotic and antihistamine in her shopping basket.

But on that day she “refused any medical assistance,” according to SAPD. It was 108F that day, the hottest day of 2024. The National Weather Service had issued a multi-day excessive heat warning for San Antonio. And Witzel had schizophrenia, a thought disorder centrally characterized by anosognosia, or a lack of insight into one’s own illness.

“I go to neighborhood meetings,” Timofeyev told me in the days after she died. “I talk to cops. They know mental health is an issue. But they ignore it.”

“If they had helped her that day,” he said, “she would be alive. She wouldn’t have died.”

But it wasn’t just SAPD. Also found in Witzel’s shopping cart: paperwork from a private psychiatric facility dated August 15, indicating “there was no probable cause to believe the decedent was a substantial risk to herself or others.”

‘Do Y’all Own a Gun or Shotgun?‘

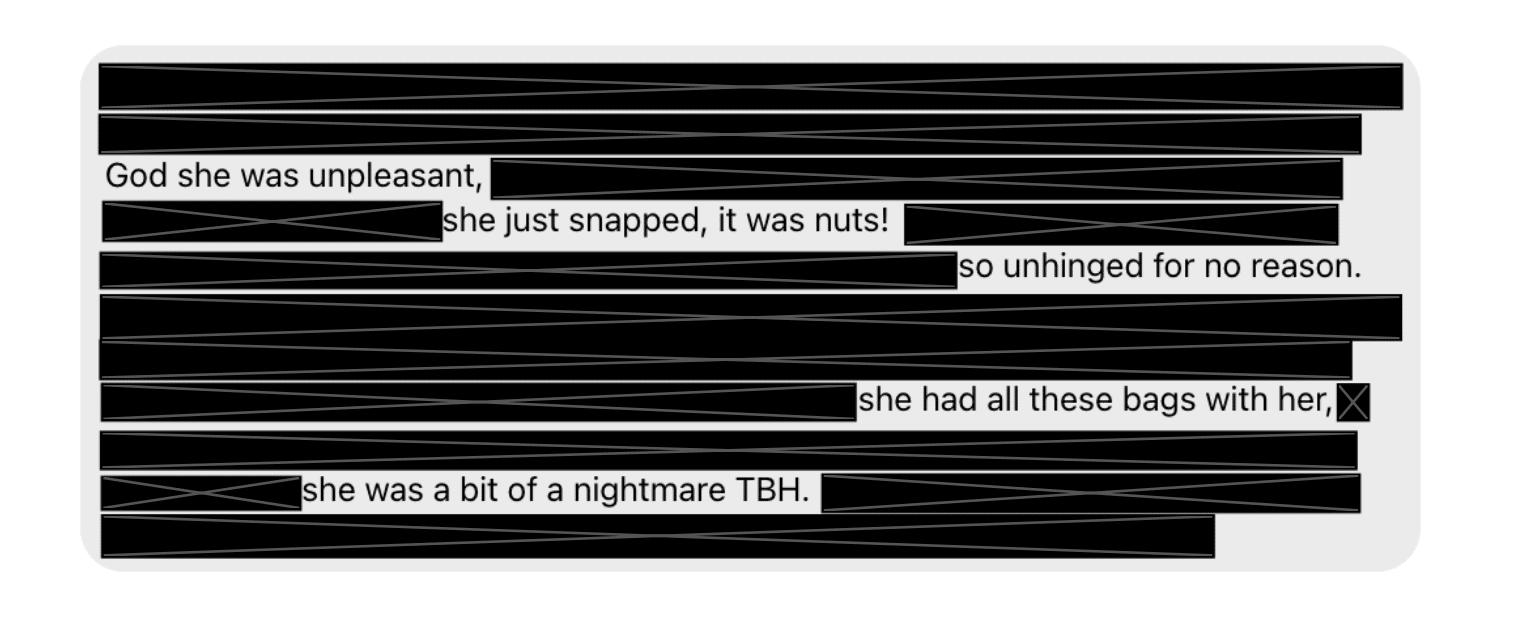

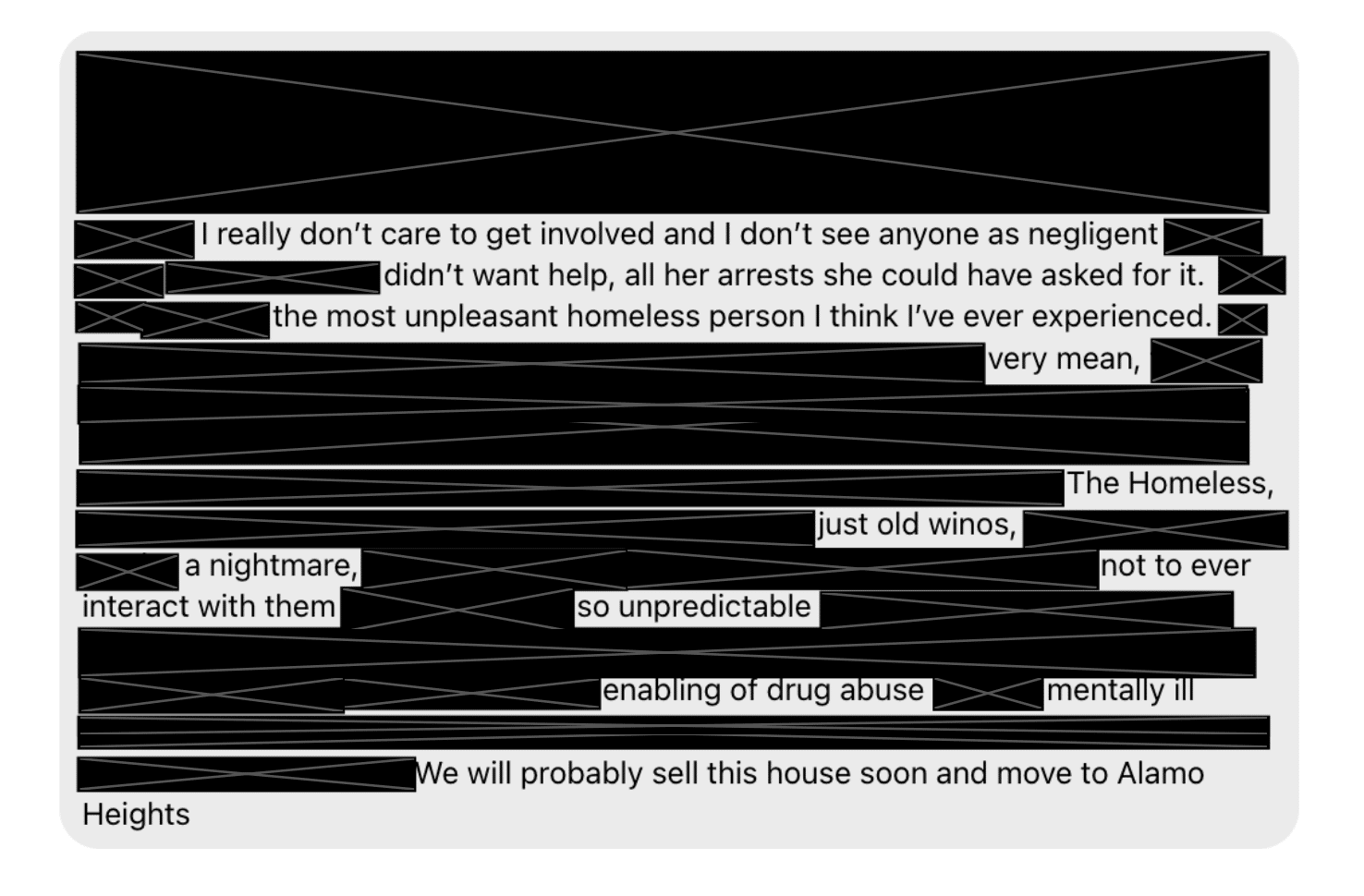

While Timofeyev had been sympathetic, other neighbors sent messages giving expression to the dehumanizing rhetoric that often accompanies conflicts between housed residents and their unhoused neighbors, especially online.

One neighbor mentioned by Timofeyev (name withheld to protect their privacy) declined to share their side of the story when asked, but in response to Deceleration’s request sent an email describing Witzel as a “thug” and a “cancer to our neighborhood.”

Another neighbor (name also withheld) sent an Instagram message saying she had seen Witzel just a few hours before she died, lying down around 11 a.m. on the steps of the Amalgamated Transit Union building across the street from San Pedro Park. She thought it was odd to see her sleeping there since it was already so hot. But she recognized Witzel, having seen her around the neighborhood before; once she saw her taking roses from her neighbor’s rosebush. Told to stop, she said, Witzel became extremely upset, yelling at her incomprehensibly. All of these details about the last hours of Witzel’s life came wrapped in such disparaging language it was unclear if the writer even recognized it as such.

Asked if she might be open to meeting and sharing more about what she observed that day, this neighbor declined to respond, but said when she saw Witzel lying in the heat, she’d considered calling police to check on her. But then Witzel sat up and looked fine, so the neighbor decided against it: she hadn’t wanted to get involved. Before moving into the neighborhood to “fix up these houses,” she said—possibly a reference to investment ownership or house flipping in San Antonio’s gentrifying near-Northside neighborhoods—she hadn’t had much experience with unhoused people. She was considering leaving Five Points, she lamented, and moving to Alamo Heights, San Antonio’s one-time racially restricted, old money neighborhood.

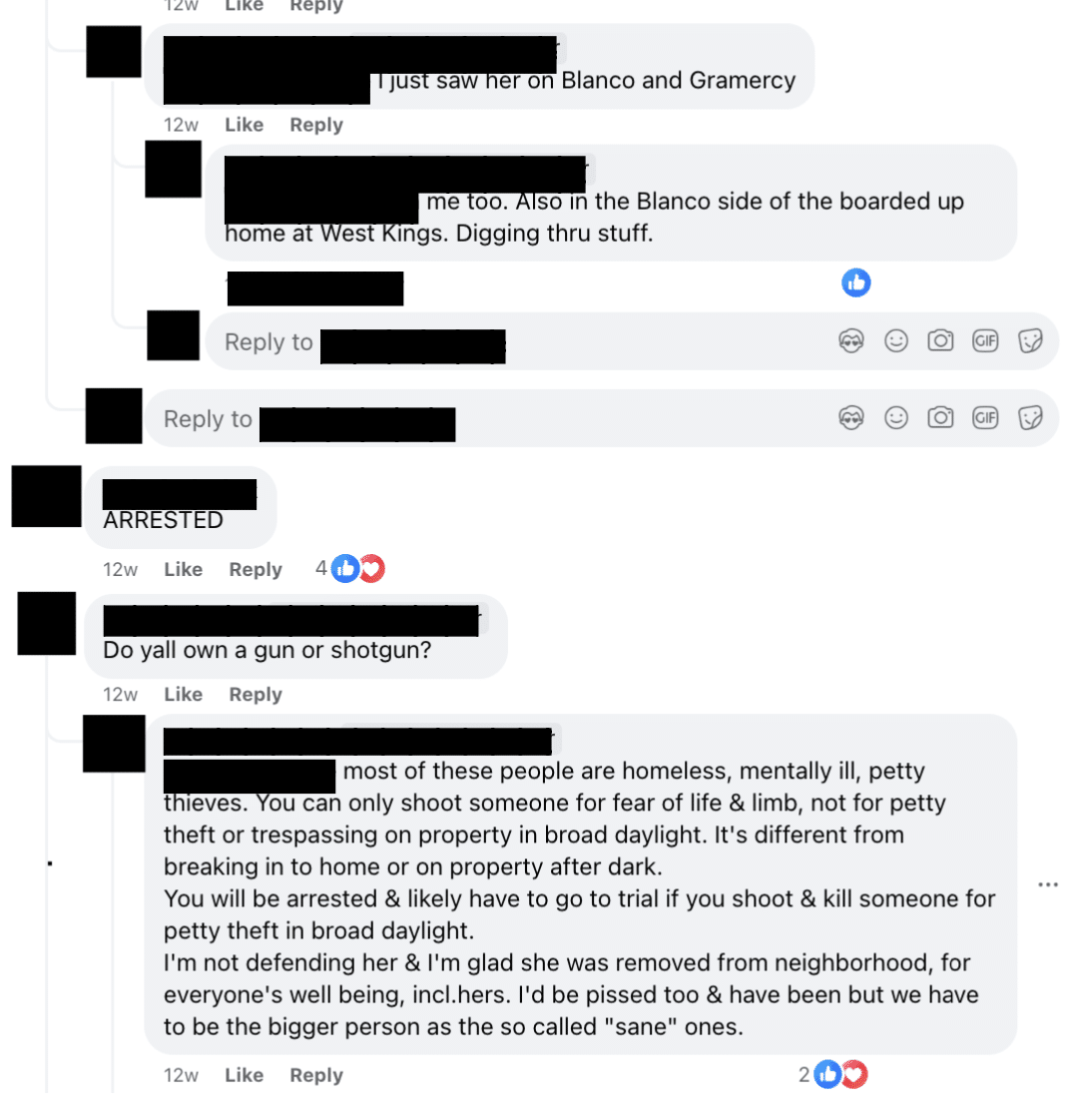

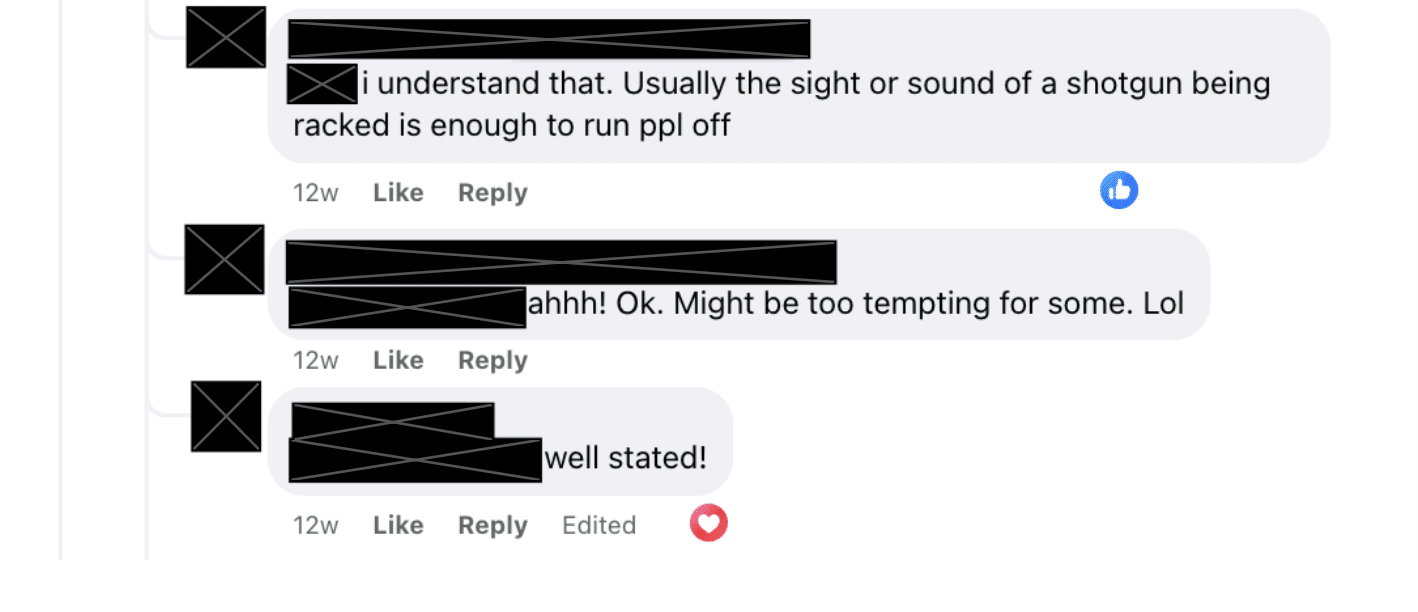

Screenshots from a neighborhood Facebook group on the night of Witzel’s final arrest on June 13 show some housed residents taking these attitudes to their logical conclusion. Though countered by others urging cooler heads or more upstream solutions (“what if we just gave people what they needed instead of trying to arrest our way out of a problem?”), some group members hinted at violence the night she was arrested for stealing 53 metal pins and an iron box.

Responding to photos of Witzel on Facebook, one neighbor asked:

“Do y’all own a gun or shotgun?” Other photos of SAPD cuffing Witzel prostrate on the street prompted another poster to announce:

“We are successful Nightstalkers/Bounty Hunters! Hit us up.”

This is not to say these neighbors did not have valid concerns for their safety. But it is to say that these safety concerns are rooted in the same systemic failures Witzel’s family encountered in trying to access adequate medical care and housing for a loved one unable to care for herself.

It is also to say that, in the complete failure of these systems, “the neighborhood” becomes the site of a struggle between two competing and seemingly zero-sum visions about who belongs there—who counts as a neighbor—and thus who deserves safety. And in a rapidly heating world, that distinction in effect proves to be a difference between life and death.

What might have been otherwise if, instead of looking away or dehumanizing those with serious mental illness or banding together to protect each other’s property, neighbors had banded together to push those in power to create real options for people like Jessica Witzel—too ill to stay safely housed in the community, not ill enough for civil commitment, but dead if left to the sweltering streets?

Coda: An Automated Message

On September 3, almost two weeks after Witzel passed, her father James Dwyer got a callback from someone at Center for Health Care Services, where Witzel was diagnosed with schizophrenia in February 2023. The message was for Witzel herself. It auto-generated a text that her dad forwarded to Witzel’s sister:

Hi, this message is for Jessica Witzel. I’m calling with the Center for Health Care Services. If you could please return my call at this number. I’m available Monday through Friday from 830 to 530pm. Have a great day.

So Dwyer called back, and it rang and rang. Then a recorded message delivered what he described as complicated instructions and three different phone numbers—all this “to a supposedly mentally unstable person,” he texted Coleman.

“And then they had a full mailbox so I couldn’t leave a message. This is the quality of ‘help’ you get from Texas.”

This Can’t Be the Final Word

I received one last message in the days after Witzel’s story broke, from someone in Austin named Sonja Burns. Burns is the twin sister of a man who has lived in the Austin State Hospital for 15 years, and for him she has been “working tirelessly on the continuum of care for those with the most complex mental and behavioral health needs for MANY years.”

Burns forwarded me a story about a man in Austin who for decades shuttled between jail and hospital and the streets before finally dying in Travis County Jail while waiting for a psychiatric bed to open up. She forwarded a request for public comment for a hearing at the Texas Capitol on expanding the state hospital system. What was most needed, she said, is “residential options in between hospital level care and community placement” to meet the true level of need required by those “‘too acute’ to meaningfully engage in voluntary services, but not acute enough for inpatient care.’”

“Until systems are empowered to address a person’s true level of need,” she continued, “and account for those they cannot currently serve because the infrastructure within our continuum of care and housing does not include them, we will continue to perpetuate the cycle of trauma at a great fiscal and human cost.”

After reading these words, this final message, I sat outside in the relative cool of the evening, tears building in my eyes. A cool front had pushed through the night before, the first one of the year, and in my body on some primal, basic level I could sense another summer had broken. If only Jessica could have made it one more week, she too could have felt the blessing of that shift against her skin like a breeze, the turning of the season whispering deep inside her bones: we survived. Just one more week might have bought all of us more time to organize and fight for real options.

Still, Burns’s email signoff buoyed me.

It buoys me still, it bears repeating here:

not giving up! - sonja,

she wrote.