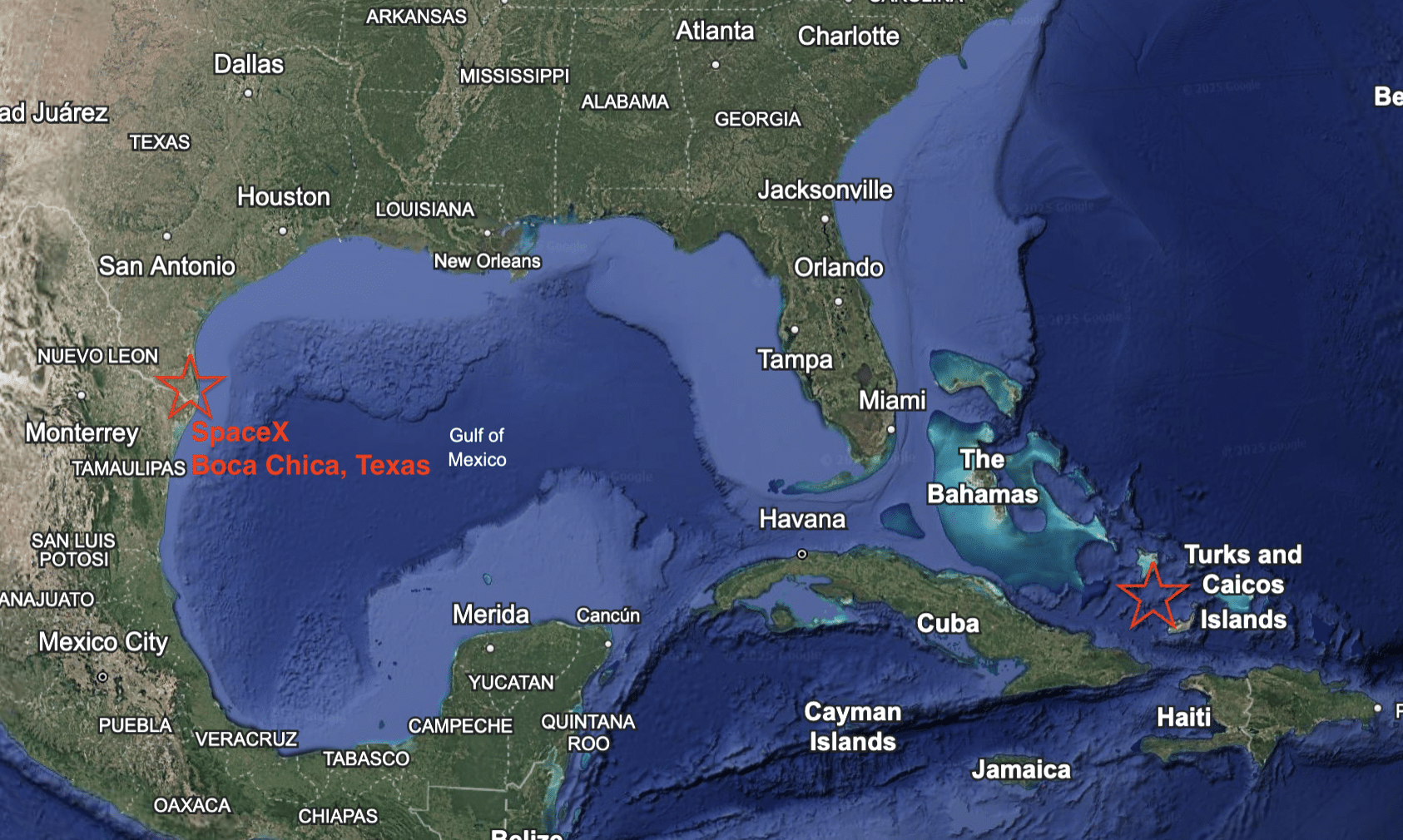

SpaceX’s first Starship launch from South Texas in 2025 ended last Thursday much like most others have: in an explosion. Rather than debris raining down in Port Isabel and around Boca Chica Beach, however, properties in the Turks and Caicos Islands were subject to pieces of Starship, according to the Federal Aviation Administration.

While residents nearby sue the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality for granting SpaceX a permit to discharge wastewater into sensitive wetlands, those on the receiving end of possible Starship reentry blunders—including Hawaii and Australia—are also now raising concerns over plans to increase the number of launches.

The FAA begins its investigation into the explosion by grounding the Starship program. Meanwhile, the agency is considering whether the company can increase its annual launches from 5 to 25 as those in the program’s immediate shadow continue to demand that their complaints be addressed.

FAA hearings

The recent FAA convening in the Rio Grande Valley came on the tail end of a polar vortex gracing the Rio Grande Valley the first week of January, dropping temperatures and bringing cloudy skies to Brownsville. Near the Gateway International Bridge downtown, the fogged windows of Texas Southmost College’s auditorium leaked orange light and illuminated the gray of the day.

Inside, about 150 or so people—roughly 0.0008 percent of Brownsville’s population—gathered for the FAA’s public meetings on SpaceX’s plans to quintuple its launches from five to 25 per year from South Texas. The heater wasn’t on in the auditorium, so the expansive room was only slightly warmer than outside, where residents were already giving television interviews questioning how much these plans would impact them. According to the FAA, not very much, if at all.

Read the FAA’s ‘Revised Revised Draft Tiered Environmental Assessment for SpaceX Starship/Super Heavy Vehicle…‘

“If three or four launches is an inconvenience, what’s 25 launches going to cost, a total shutdown of Boca Chica Beach?” Rene Medrano, a longtime resident of Brownsville who lives near SpaceX’s facilities, said to me at the morning meeting. “I mean, how can it not do that?”

Yet that’s precisely the FAA’s position as it works to update the 2022 Environmental Assessment (EA) of the company’s Starship program. More launches don’t mean more road closures, it says, because the company has grown more efficient. More launches won’t “significantly” impact the nearby communities despite “unavoidable impacts” like losing beach access, increased traffic and noise. And those sonic booms that the Super Heavy booster causes when it returns to Earth won’t harm human hearing because, citing a decades-old study, no evidence has shown that they do under the limits the FAA predicts will come from them.

(At the meeting, FAA spokesperson Amy Hanson told me the agency has no comment on a recent study that showed Starship’s October 13 launch exceeded FAA’s sonic boom pressure predictions.)

The current five launches are allowed under the FAA’s 2022 EA of the company’s Starship program. SpaceX increasing its Starship launches, or cadence, to 25 a year would mean 2 to 3 rockets leaving the beach a month.

The Laguna Madre area—Port Isabel, Laguna Heights, Laguna Vista and South Padre Island—is already seeing the company negatively affect day-to-day life, whether from traffic or, for those who live closest to SpaceX’s facilities, power outages and indifference from the company.

Before SpaceX can launch more than it does now, it needs another EA from the FAA. A draft version of that proposal was released to a small sliver of the Brownsville public at two in-person meetings that day.

Attendees were allowed to make public comments via a court reporter after listening to a half-hour presentation. There was no town hall, no way for community members to hear what each other had to say, which is what some people I spoke with at the meetings expected. Instead attendees were directed to nearby SpaceX employees and environmental consultants to answer their questions.

How can more launches mean similar or less impacts, was the question on many attendees’ minds.

Related: ‘Why Elon Musk’s Demand for Suffering Won’t Stop at Mars‘

I asked Hanson to answer the road closure discrepancy. She said SpaceX has reduced how often it closes Highway 4 by 85 percent. This reduction, she said, was because of the company’s separate testing site on Massey Road, the former site of a gun range just off of Highway 4.

But according to the Draft EA, that road closure reduction occurred only between SpaceX’s first Starship launch and its third. There are no other details in the Draft EA about the reduction, how it was calculated, and whether that percentage was retained. SpaceX has flown three more Starships since, and there are no mentions in the draft EA whether there are less closures from the third launch to the sixth.

All this talk of no negative impacts is hard to follow given the pace of operations has required obvious tradeoffs.

Allowable closures of Highway 4, for instance, were set at 180 hours initially when the site was only going to launch Falcon rockets from a “small, eco-friendly” facility. But as the rockets grew in size, Texas Parks and Wildlife increased SpaceX’s allowable road closures up to 300 hours per year, as agreed to by Cameron County, and again in 2022 up to 500 hours a year.

With 25 launches a year comes more trucks to fuel the rockets, which was not mentioned during the presentation. Truck traffic will increase from 3,850 to 18,421 vehicles a year. This amounts to 50 trucks a day, on average, driving down the perpetually-damaged Highway 4, the lone road in and out of Boca Chica and SpaceX’s South Texas facilities, compared to 10 a day.

The consultants, some of whom wouldn’t identify who they worked for when asked by attendees, were from SWCA and ICF, the latter of which has been helping SpaceX with environmental consulting for several years. SWCA was contracted by the FAA to draft the document explaining SpaceX’s plans.

All my questions to one consultant, who told me anything he said was off the record, were answered with references to the National Environmental Policy Act and how the EA was done in accordance with the FAA’s “significance thresholds.”

The FAA has certain criteria on what significantly impacts a facet of the environment surrounding a project, like for groundwater and wetlands. But the FAA doesn’t have significance thresholds for hazardous materials, natural resources, and energy supply, socioeconomics, environmental justice or children’s health. In the Draft EA, the agency says more SpaceX launches wouldn’t “significantly” impact any of these factors.

On lawsuits & raining debris

Days later, the FAA held a virtual public meeting on January 13, during which attendees raised a concern not talked about often: where the rocket lands.

When debris rained down on the Turks and Caicos Islands, SpaceX said that it all fell into a “designated hazard area.” However, the FAA had to divert air traffic when Starship exploded. The FAA only does this when rocket debris falls outside of a designated hazard area. But debris fell just off Texas’ coast, too. Local ABC affiliate KRGV, covering the launch from Matamoros’ Playa Bagdad, filmed debris falling into the water.

SpaceX plans to send its Starships to splashdown off the coasts of Hawaii or Australia. Residents of both are demanding the FAA assess how Starships landing in those oceans will impact the environment, meaning SpaceX’s plans appear deficient from launch pad to landing zone to the people who live near them. People have resisted each time the FAA has rewritten the EA it approved for SpaceX, calling for a more thorough analysis like an Environmental Impact Statement—a years-long study that SpaceX last received in 2014.

Experts say the FAA incrementally measuring impact as SpaceX grows and launches bigger and stronger rockets does not accurately understand what’s happening to Boca Chica Beach and beyond.

“You can’t honestly get a handle on environmental impacts this way,” Kenneth Teague, a former Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) scientist who worked on Texas wetlands, told me. “SpaceX is basically creating their own cumulative impacts out there. The goal posts are being moved every time we review one of these EAs.”

Like the one before it, this Starship launch took place in the afternoon, causing a traffic jam on the Queen Isabella Memorial Causeway right as locals headed home from work.

This was the start of SpaceX’s rhythm going into the new year. More noise, more traffic and more acquiescence from regulators. The SpaceX-themed bar in Port Isabel is expanding its dining room. Themed Cybertrucks cruise the island’s Padre Boulevard. Pre-launch bonfires at Boca Chica Beach are becoming routine.

The City of South Padre Island declares itself, via signs on Padre Boulevard, a “cosmic getaway.” Locals having to work their schedules around SpaceX launches can’t get away, however, and some of those people tried to make that known during the FAA’s meetings in Brownsville. Residents did the same in October when the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) came to the city.

Unlike the FAA, TCEQ allowed people to openly comment and ask questions about SpaceX’s actions in Boca Chica Beach.

TCEQ and the EPA, earlier this year, said SpaceX had violated the Clean Water Act by allowing industrial wastewater—the runoff from the deluge—into the wetlands that surround the launch pad.

After both agencies fined SpaceX around $150,000 for the violations, the company applied for the wastewater discharge permit more than two months after the TCEQ said it was due.

At that October meeting, TCEQ representatives in Brownsville suffered an hour of withering criticism from residents who said the regulator had already made up their minds and were going to give SpaceX whatever it wanted regardless of what they said. Two months later, TCEQ issued the permit.

Organizers sued the TCEQ in response, alleging the regulator gave SpaceX a pass to continue violating the Clean Water Act. Texas Rio Grande Legal Aid (TRLA) filed the lawsuit on behalf of South Texas Environmental Justice Network (STEJN) and the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe of Texas.

“It’s a pattern of unwavering favoritism toward SpaceX,” Paola Camacho, a TRLA attorney representing STEJN in the lawsuit, said in a statement.

South Texas Environmental Justice Network’s Contested Case Hearing RequestDownload

Multiple sonic booms

This past Friday, January 17, I watched the launch from a parking lot on Adams Street in Port Isabel, alongside a handful of locals and around a hundred unfamiliar faces. Hidalgo County Sheriff’s officers were there to keep people in a designated area of the lot, despite Port Isabel being in Cameron County. In between two rows of homes on a man-made channel was the original launch pad, the second being constructed out of view. The rocket went up and the booster came back down, where I heard, and felt, multiple sonic booms for the first time.

The FAA’s analysis of SpaceX’s launch plans describes how a sonic boom is felt and heard based on several factors. However those factors figured in, this must have been the perfect confluence for me to experience the loudest thing I’ve ever heard. Guns I’ve fired are a close second.

To imagine this happening 25 times a year, regardless of the FAA promising that it and SpaceX will work together to warn the public ahead of the noise, brought up another question not really addressed by either: what is it all for? Is a future on Mars for people who don’t exist yet worth making peoples’ lives on Earth, in Port Isabel, so conditional? Mars colonization is the company’s answer, moon missions are the agency’s. But the latter can only be achieved by the former, according to SpaceX’s CEO Elon Musk. So, is Mars colonization a priority for the U.S. government, a policy position even?

President Trump declared that to be the case, promising in his inaugural address on Monday to put a U.S. flag on the red planet. Musk, in the audience, receiver of billions in federal contracts to get to there, gave two thumbs up in response.

A few hours later, Musk couldn’t resist tossing in a fascist-style salute to fans.

Die Zeit, a prominent German publication, titles its article: 'A Hitler salute is a Hitler salute is a Hitler salute.'

— Taniel (@taniel.bsky.social) 2025-01-21T17:22:55.702Z

Teague challenged the wisdom of the Mars mission in the public comment he submitted to the FAA, pointing out perhaps the most inarguable, and hardly mentioned, concept of the journey to the red planet through the Laguna Madre area.

He wrote:

“The worst place on Earth, the worst time on Earth, is far more hospitable to human life than the best place on Mars, or the best time on Mars.”