A serious rate hike may be coming down the pipe for San Antonio-area water users. Presented to members of City Council earlier this month, the proposed increases would raise customer rates year-over-year for three years. Ultimately, bills would balloon more than 30 percent, according to News4SA.

This was not received well by Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones and Council. CPS Energy, meanwhile, is also expected to line up for an increase if not this year, then next. Increasing rates isn’t welcome news in a pinched economy. That pain is compounded when you know that the largest, wealthiest residential users have their own reduced-cost rate class at CPS Energy.

The flat-fee elements of SAWS’s rate structure raise similar concerns about unfairly punishing the most frugal water users. For many years, Trinity University’s Meredith McGuire parsed utility rates at CPS and SAWS. She regularly pointed out inequities and lobbied for reforms as a member of the local Sierra Club and various environmentally minded coalitions.

Recently, her husband Jim Spickard, also an academic by background and (also) recently retired (he from University of Redlands), picked up on some of her work to carry it forward. His white paper titled “ANALYSIS OF SAN ANTONIO WATER SYSTEM’S RATE STRUCTURES: 2005-2025” found room to praise SAWS while highlighting recommendations for further rate reform.

Spickard distinguishes between "rates" and "rate structures." The first sets how much people pay per gallon of water, which is often the lowest part of a residential SAWS bill. ‘Rate structures’ determine how much of a user’s bill goes to water and how much to other fees.

These include a flat fee for being tied into the water system, a flat fee for sewer service, and various “pass-through” fees levied by other organizations. He points out that the most frugal water users pay more in such fees than they do for water itself. For example, those using less than 4,000 gallons of water per month pay the same “Service Availability Charge” as do those who use two or three times more water.

“That charge makes up 43% of the bill for 5,000-gallon users, 18% of the bill for 10,000-gallon users, and 7% of the bill for 20,000-gallon users. It is a regressive fee because it hits low-volume users harder,” he writes.

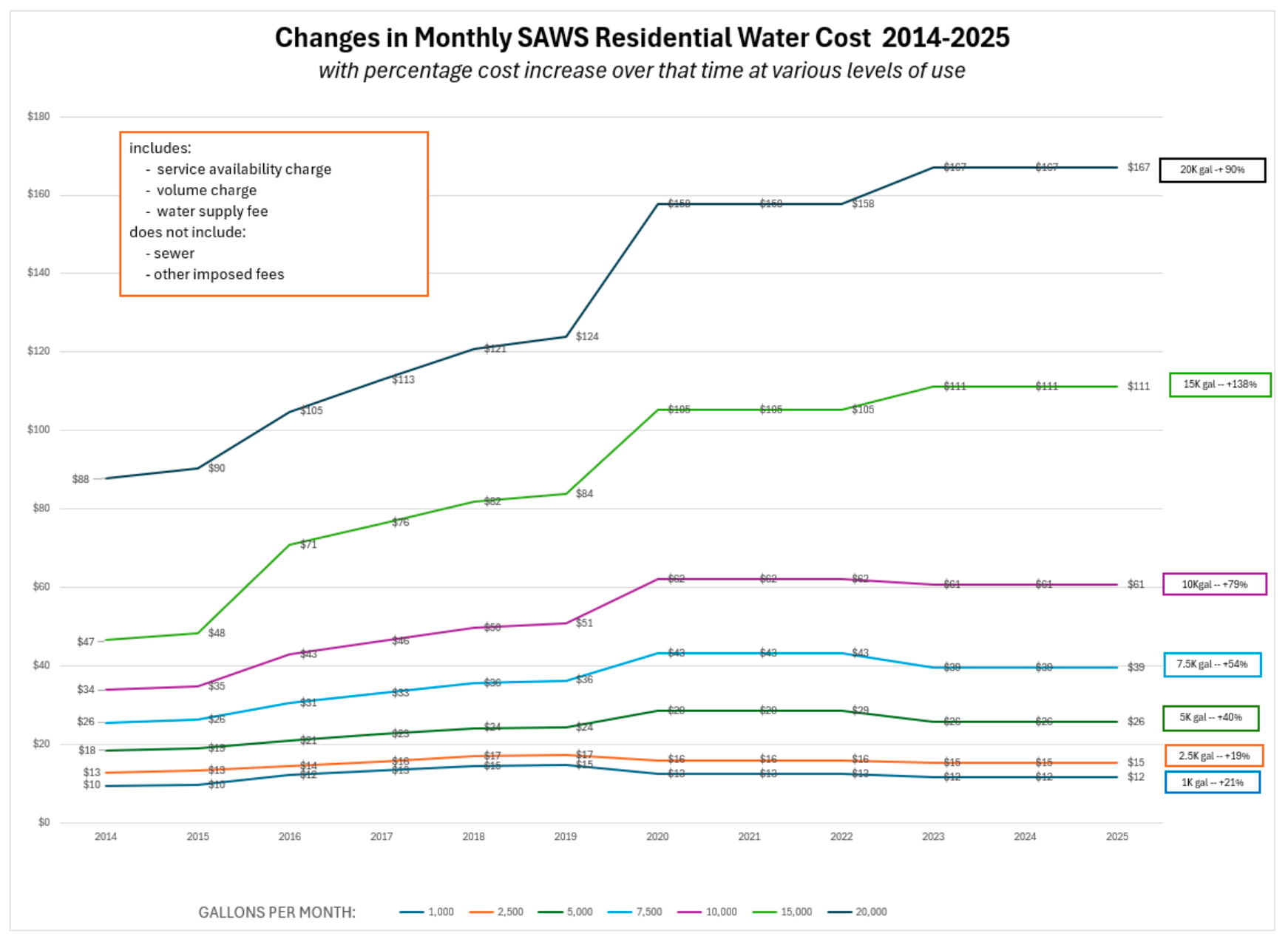

While SAWS bills have been rising for years, recent rate reforms actually lowered the percentage of SAWS’ budget that low- and moderate-income SAWS customers must carry. Rate tiers were modified in 2016, taking some of the weight off lower users and shifting it to higher users, in hopes of encouraging more water conservation. In 2020 and 2023, the Service Availability Charge was lessened for low water users. Water rates in 2023 also saw reductions for low users and increases for high users—“making the overall Residential Rate Structure more progressive in 2025 than it was in 2014.”

That said, there is room for improvement—especially, perhaps, when it comes to the largest users: business and multi-family (or “General Class”) customers. Their rate structure provides virtually no incentive to conserve water, Spickard’s analysis found. And their per-gallon rate was, for many, well below that of Residential users. Essentially, any company using more than 10,000 gallons (or more) per month is getting a discount over what Residential users pay. The 2023 rate reforms improved this situation, with the bottom half of Residential users paying less overall than they were a decade earlier. Still, the gaps between Residential and General Class rates weren’t erased.

“By lowering the Residential Class Service Availability Charge and making the tiered per-gallon rates more progressive, the 2023 rate restructuring lessened the burden on low-using ratepayers,” Spickard writes. “While apartment houses, businesses, schools, and so on may find it harder than households to limit consumption, SAWS should explore possible incentives.”

Perhaps a rate class could be created to inspire those heavy users to implement greater conservation efforts, he writes. “In my view, the 2023 rate structure is not perfect, but it better expresses San Antonio’s commitment to equity than did those when I first started observing the rate structuring process. I hope it can continue to improve.”

After all: “A gallon saved is a gallon added to SAWS water supply.”