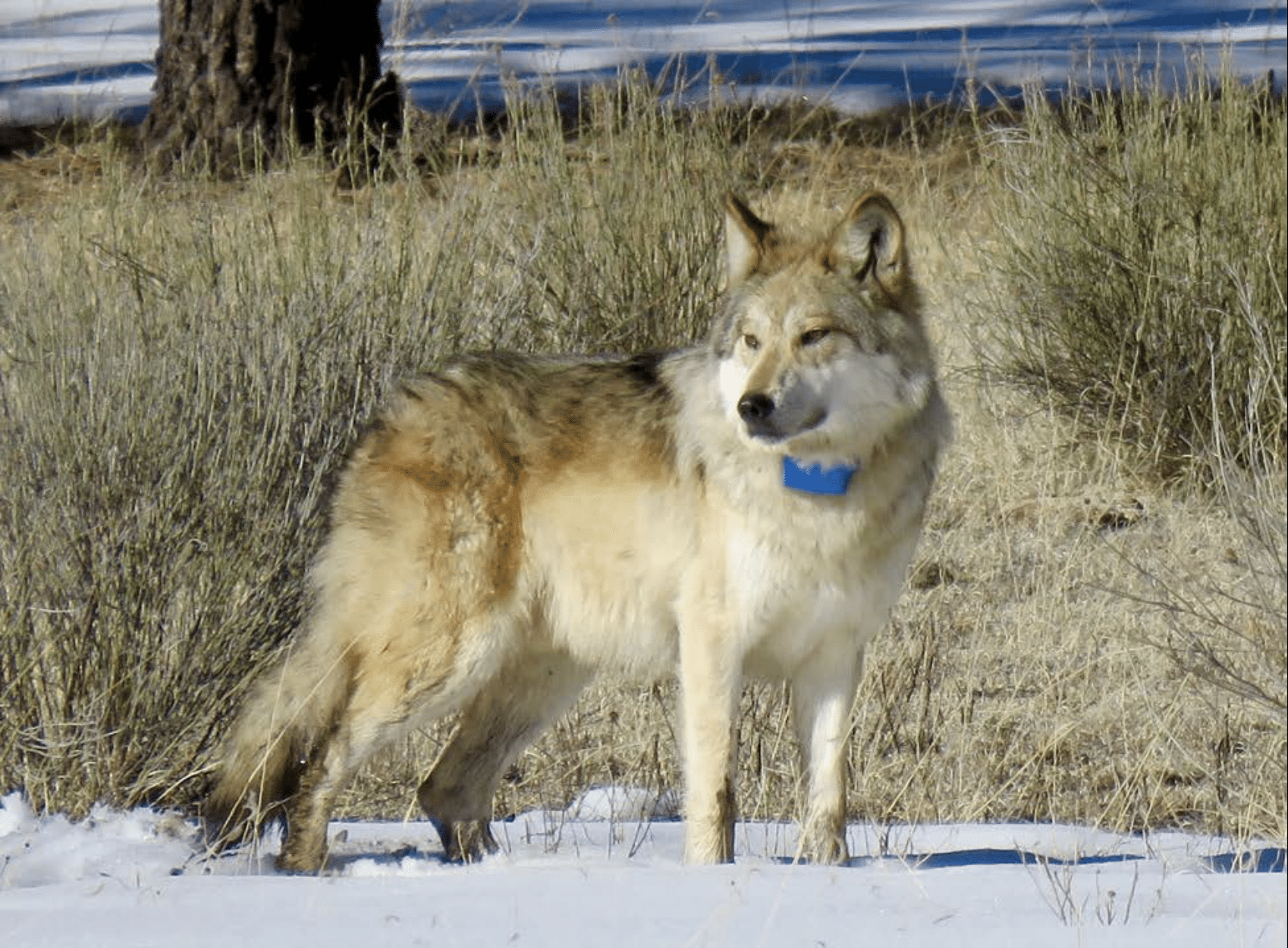

Brady McGee lies on his belly, his head inside a Mexican gray wolf den. With gloved hands, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Mexican Wolf Recovery Coordinator delicately transfers newborn, still-blind pup wolf pups onto a tarp outside the den. Another biologist takes captive-born pups—which they’ve hiked into the forest with—from his backpack and places them on the tarp, where they wriggle and prance over each other. They will soon be placed inside the den. This cross-fostering increases the population’s genetic diversity, and is one of several avenues pursued by biologists to recover this endangered species.

“We feed, chip, and vaccinate them, and once we’re ready to stick them back in the den, you stimulate them to make them pee and poop on each other,” said McGee in a 2022 interview. This ensures that the mother wolf will accept the fostered pups as her own.

To succeed, “everything has to line up perfectly,” said McGee. The pups get fed every four hours as they fly from breeding facilities across the country to Arizona or New Mexico, the only places these wolves live in the wild besides a small population in Mexico. Once the flight lands, the team drives several hours in the Gila or Apache-Sitgreaves national forests and then hike, pups on backs, to the selected wolf den.

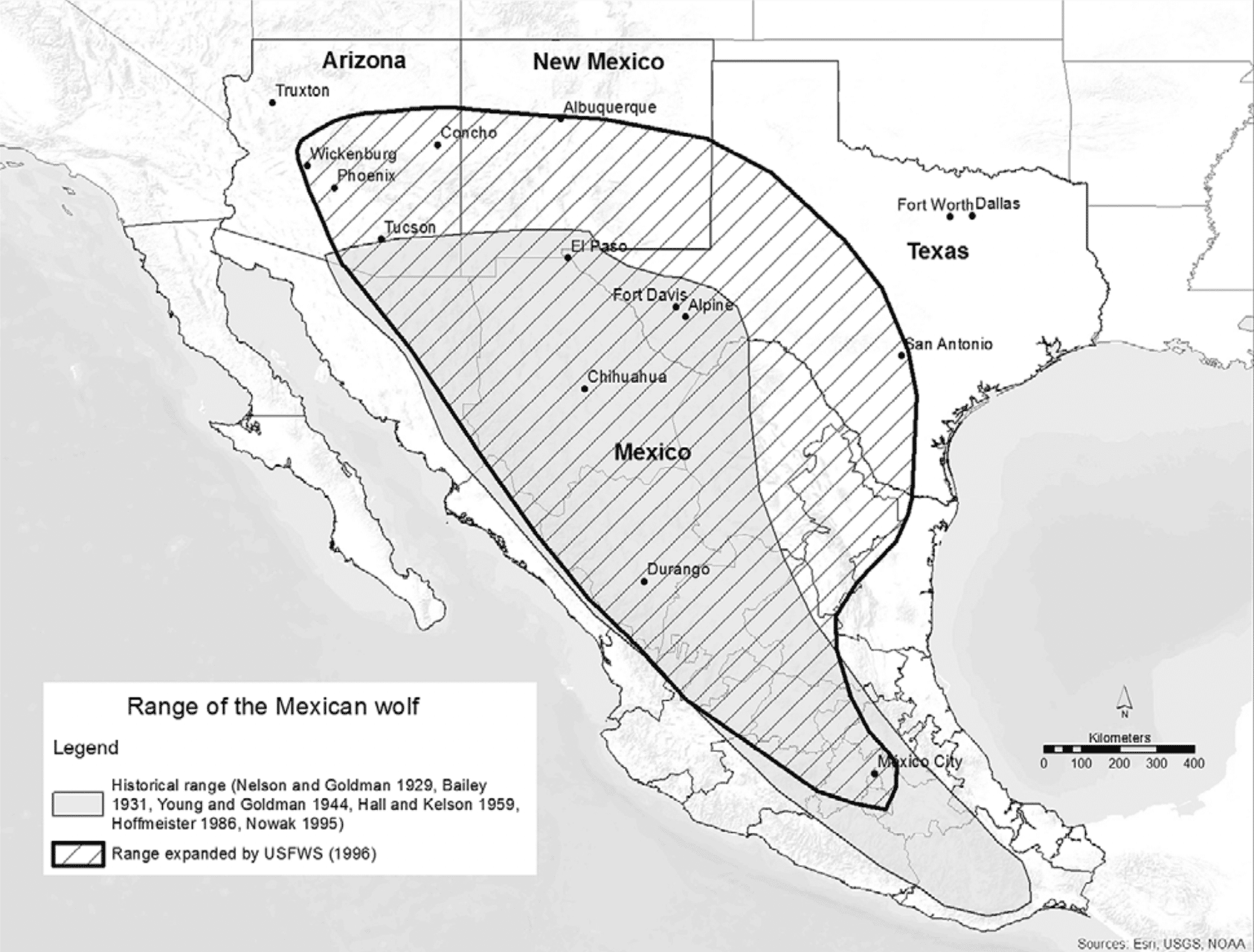

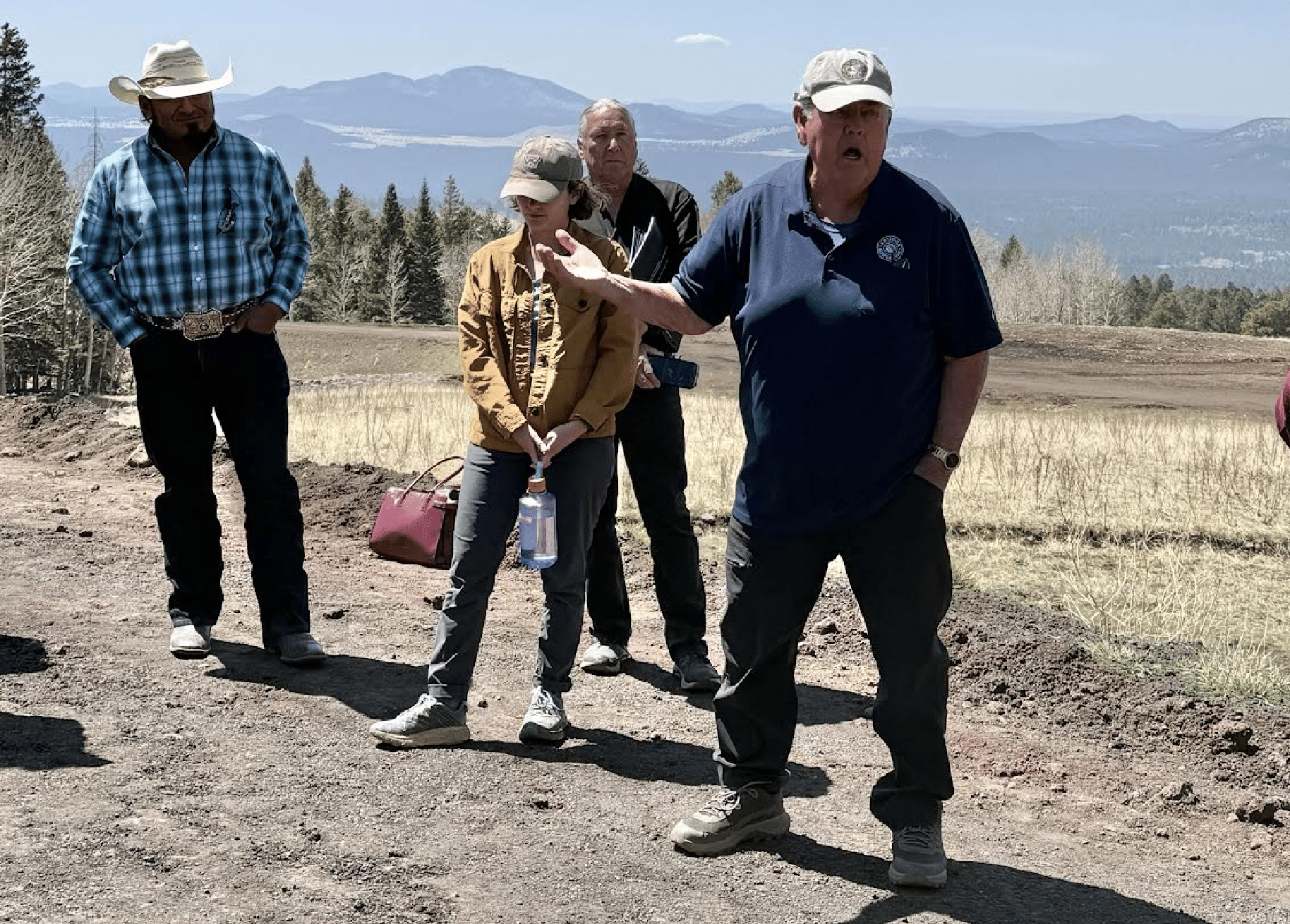

A distinct subspecies of their much larger gray wolf cousins, Mexican wolves (Canis lupus baileyi) once roamed throughout northern Mexico and the southwestern U.S., including southeastern Arizona, southern New Mexico, and western Texas. When colonists came to the southwest, they brought livestock to this “land of milk and honey,” said Jim deVos, Mexican Gray Wolf Recovery Coordinator for the Arizona Department of Fish & Game, speaking at an April Society of Environmental Journalists tour of wolf habitat in Arizona. “They also found wolves, and throughout the history of the world, wolves and livestock don’t mix well—in the eyes of the livestock owners.”

Back then, federal agencies, colonists, and ranchers purposefully killed wolves, encouraged by government bounties. Wolves were burned alive and dragged to death behind horses, their skulls and skins piled high for photographs to commemorate victory over the so-called vermin. “They would use gas in dens. They would shoot on site. It was a merciless onslaught to get rid of them,” said deVos.

From Extinction They Arise

By the 1970s, Mexican wolves were extinct in the U.S. and hanging by a thread in Mexico, when—spurred by changing public sentiment and the Endangered Species Act (ESA)—scientists became determined to recover the species. Between 1977 and 1980, trappers set out to capture the last remaining wolves, finding just five individuals. These were added to two captive populations, forming three lineages. Then captive breeding began in earnest.

Nearly two decades later—but only after a 1992 ruling forced FWS to make a plan to reintroduce wolves into the wild—11 Mexican grays were released on March 29, 1998, into Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests in eastern Arizona, bordering Gila National Forest in New Mexico.

Dave Parsons, USFWS’s Mexican Gray Wolf Recovery Coordinator at the time, recalls setting those first wolves free, after some setbacks. First, a major blizzard hit Arizona. Then a county ranching organization filed an injunction to stop the release. But nothing could stop fate. Before the judge had even seen the lawsuit, the team brought the wolves in three family groups to their final destination in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests. “We opened the gates at dusk,” says Parsons. “It was exhilarating, the culmination of nearly eight years of planning.” The judge later threw out the lawsuit.

Released under the ESA’s 10(j) rule, these wolves were, and still are, considered an “experimental non-essential” population. The rule has become a cornerstone of endangered species recovery and results in less public pushback by giving government agencies more leeway to handle human-wildlife conflicts and other management decisions.

The wolves expanded their population since, bolstered by releases of additional wolves and cross-fostered pups. “We have had nine consecutive years of population growth,” said deVos. “Today, we’re at 286, at least, and we know that there are some that we’ve missed.” At least one tribal nation in the region has wolves but has chosen to not publicly disclose the numbers.

Are We Recovered Yet?

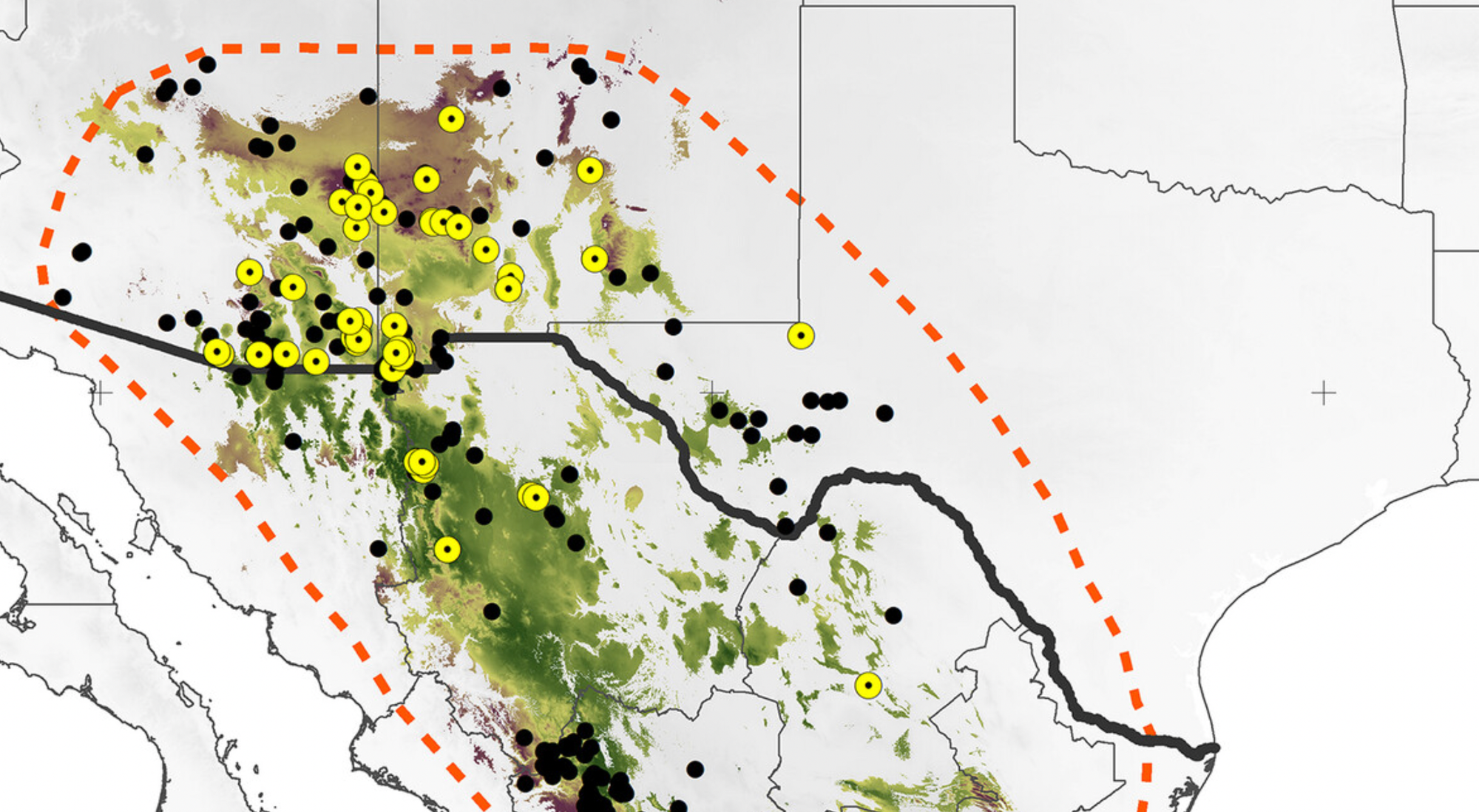

Mexican wolves currently exist in two isolated populations: the northern Mexico population in the states of Chihuahua and Sonora has floundered, having just 35 to 45 animals, while the population in Arizona and New Mexico has thrived—with caveats.

“Most of us in the wolf business feel that, from a demographic standpoint, we’re a year or two away from meeting the number that’s mandated in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Recovery Plan,” said deVos. Not everyone agrees they’ll hit the target soon; deVos has a $5 bet with a colleague on his hunch.

The current criteria for downlisting Mexican wolves from endangered to “threatened” is an average of at least 320 animals over an four-year period with a minimum of two distinct populations, or two populations, each with an average of 150 animals showing positive growth rates. Both options require the wolves to have healthy gene pools.

Several scientists and science-based environmental groups, including the Western Watersheds Project and the Center for Biological Diversity, argue that the target of 320 wolves is far too low. Among the 286 wolves in the U.S. population, there exist just 26 breeding pairs. Pups face long odds; around 50 percent die in their first year. Poaching of wolves is also common.

USFWS published its first Mexican Gray Wolf Recovery Plan in 1982 without a recovery target since the government had not yet approved reintroducing wolves. Draft revisions in 2005 and 2013 required 750 animals and a recovery area throughout Arizona and New Mexico—including northern portions currently excluded—as well as southern Colorado and Far West Texas. Political pressure kiboshed both of those ideas.

“There was a lot of high level political pressure on the Service,” says Carlos Carroll, an independent ecologist with Klamath Center for Conservation Research who served on the official Mexican Wolf Science and Planning Subgroup at the time. “So they went back to the drawing board.”

“The Service will never say ‘We made this decision based on politics versus science’ but if you look at the record, opposition by various politicians at the time was quite public,” says Carroll.

“For example, the governors of the four southwestern states sent a joint letter to the head of the Fish and Wildlife Service opposing the broader recovery goals.” Parsons, the FWS Director at the time, told the same story.

The final 2017 plan revision not only used the lower number of 320 wolves, but also drew a boundary for the 10(j) population (the Mexican Wolf Experimental Population Area): I-40 on the north, the California-Arizona border to the west, the Texas-New Mexico state line to the east, and the Mexico-U.S border to the South (much now blocked by border wall, hampering already extremely limited gene flow). Under the current administration, companies are bidding to construct 24.7 miles of wall in Arizona where, currently, wolves can cross.

When wolves wander from the designated area, they’re captured and returned, brought into captivity, or euthanized in rare cases. The recovery area includes habitat unsuitable for wolves, including the Sonoran desert; on the other hand, excellent habitat exists north of I-40—outside the designated area—including 36 million acres of the Grand Canyon ecoregion, although not part of their known historic range. Several organizations want wolf releases there (the Texas Lobo Coalition also advocates for releases in West Texas).

Despite boundary lines, wolves are on the move. Several have dispersed south to Mexico and north of I-40, including the first pack—two or more wolves traveling together—in Arizona last year. The female of that pack, named Hope, was found dead November 7th, 2024. FWS is investigating, with a $100,000 reward for information that leads to a conviction.

Citizen Suits Advance Recovery

On April 21, 2025, the USFWS mistakenly killed a radio-collared female wolf, Asiza, while attempting to euthanize an un-collared male that had been dining on cattle in the region. It shocked wolf advocates not just because of the death of a likely pregnant female, but also because of the mistaken identification. Collars are quite obvious. The situation is under investigation.

“The death of Asiza was a tragedy, but the removal of any of these wolves for livestock predation on public land is a shame,” says Greta Anderson, deputy director of Western Watersheds Project, a non-profit environmental conservation organization dedicated to protecting wild species and spaces across the western United States.

Anderson pointed out that many livestock killed by wolves are themselves grazing on U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management lands. “There are so few of these wolves in the wild, and thousands of cattle in wolves’ best remaining habitats, and ranchers are compensated for their lost stock,” Anderson told Deceleration. “It’s unacceptable that any Mexican wolves would be killed for eating the untended, easy prey that is ubiquitous on our forests and grasslands.”

In recent years, such legal take by agencies—even when they get the right animal—along with high depredation compensation to livestock owners has come under scrutiny, including fraud allegations. Haters can kill wolves illegally out of fear and loathing, then claim “mistaken identity.” This excuse has a name: the McKittrick policy defense. It unofficially guided the U.S. Justice Department’s handling of such cases until ruled illegal in 2017. Even so, prosecutions of wolf poaching remain rare.

In 2018, the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD), Western Watersheds Project, and others sued USFWS to force them to better address human-caused wolf mortality, particularly poaching. To date, wolf opponents have illegally killed at least 149 wolves since their reintroduction. In a victory for the plaintiffs, the 2021 ruling required USFWS to revise the recovery plan to address this.

The 2022 revision included better law enforcement protocols and livestock-wildlife conflict avoidance measures, education and outreach programs, and improved methods to prove the causes of livestock deaths. However, it failed to address other concerns.

After the new plan was published, Western Watersheds, Wildlands Network, and others filed a new lawsuit demanding USFWS use science-based decisions in the recovery strategy. They called for removing the ban that prevents wolves from crossing I-40, establishing a second U.S. population for greater chance of long-term survival, and ditching the “nonessential” 10(j) designation because, if this is the only U.S. population, how can it not be essential?

Several scientists, including Carroll, have published analyses showing that three populations with a combined population of 750 wolves with 250 animals in each subpopulation would provide a science-based recovery target, especially given their precarious genetics. Three adequately-sized populations with enough exchange to keep the gene pool healthy allows the species to sustain the litany of ongoing threats.

However, in March 2025, a U.S. district court rejected the plaintiffs’ claims, upholding the current USFWS recovery plan. Per Anderson, they have not yet decided whether or not they will appeal.

“The agencies are disinclined to do the right thing because they can’t stand the politics,” says Parsons. “Every advancement in this 25-year history of Mexican wolf recovery that has made forward progress has had to be forced by citizen litigation.”

Carroll also worries about the Endangered Species Act’s future. “I’m concerned about the effects that some of the political undermining of wolf recovery has on broader integrity of the Endangered Species Act and the way it’s applied not just to high profile species, but to all species,” he says. “If politics is driving it rather than science it will allow a lot of species to slip through the cracks.”

In April, the Trump administration proposed a rule to change the definition of “harm” under the ESA to only include direct killing or collecting of a protected species. If approved, that will dramatically reduce protections for ESA-listed species.

Yesterday, a coalition of wilderness advocates condemned the removal of two Mexican gray wolves—and their two new puppies—from a den site in southeastern Arizona.

Officials had translocated the female and her previous mate to Mexico in 2022, by they wandered back across the border. After the mate was killed in 2023, she was taken into captivity to bond with another male, then released in Arizona’s Peloncillo Mountains. Now, they’re being removed again, which is traumatizing to these social, intelligent animals as they try to raise a litter of pups.

“When this pack first came across the border in 2022, it was a conservation success story. It showed connectivity between the U.S. and Mexico populations and offered hope of recovery in the historic habitat of the species,” said Anderson of the Western Watersheds Project in a press release. “This action represents political capitulation to the organized anti-wolf factions rather than any rational approach to species recovery.”

Genetic Diversity is Key

Among the major challenges facing today’s Mexican wolves is that they all came from a small number of founders, and thus have low genetic diversity. This can increase the chance of birth defects, lower fertility, reduce litter sizes, and increase disease susceptibility, among other things (breeding with a cousin is not ideal).

“The story about genetic diversity is that the more diverse you are, the more adaptable you are,” said deVos. The good news is that the original seven founding individuals came from three distinct genetic lineages. “We are now … trying to determine the best mechanism to create genetic diversity” from the existing wolves.

This includes the cross-fostering program led by McGee. By adding pups from other lineages into a wild-born litter, once offspring grow up and breed, their genetic lineages intermingle (if this did not occur, they’d mate with closer relatives).

Another way to increase genetic diversity involves assistive reproductive technologies (ARTs). In 2017, scientists at the Endangered Wolf Center in Missouri, working with the St. Louis Zoo, artificially inseminated a captive wolf with previously frozen sperm for the first time. Advances in cryonics have also improved scientists’ ability to freeze eggs—called vitrified oocytes—which eliminates the need to immediately fertilize an egg and implant it into a fertile female.

ARTs are valid tools for wildlife recovery efforts, but not everyone agrees with their use, especially at the expense of longstanding reintroduction efforts that have proven successful.

“I’m not in favor of technological fixes for the sake of political convenience,” says Anderson of Western Watersheds Project. “I think they should be releasing captive wolf families into the wild to augment the genetic diversity. Cryogenics is a last resort; habitat protection and survival of the wild population should come first.”

Coexistence Programs

To create wider acceptance for Mexican gray wolves, coexistence programs—mandated in the 2022 revised recovery plan are reducing livestock-wolf conflicts. Programs include “range riders” (for the White Mountain Apache this translates as Na’baahii or “warrior”) who roam through cattlelands, using remote noise devices and even rubber bullets to deter wolves, targeted herd management, compensation and incentives, guardian dogs and carcass removal, among other practices.

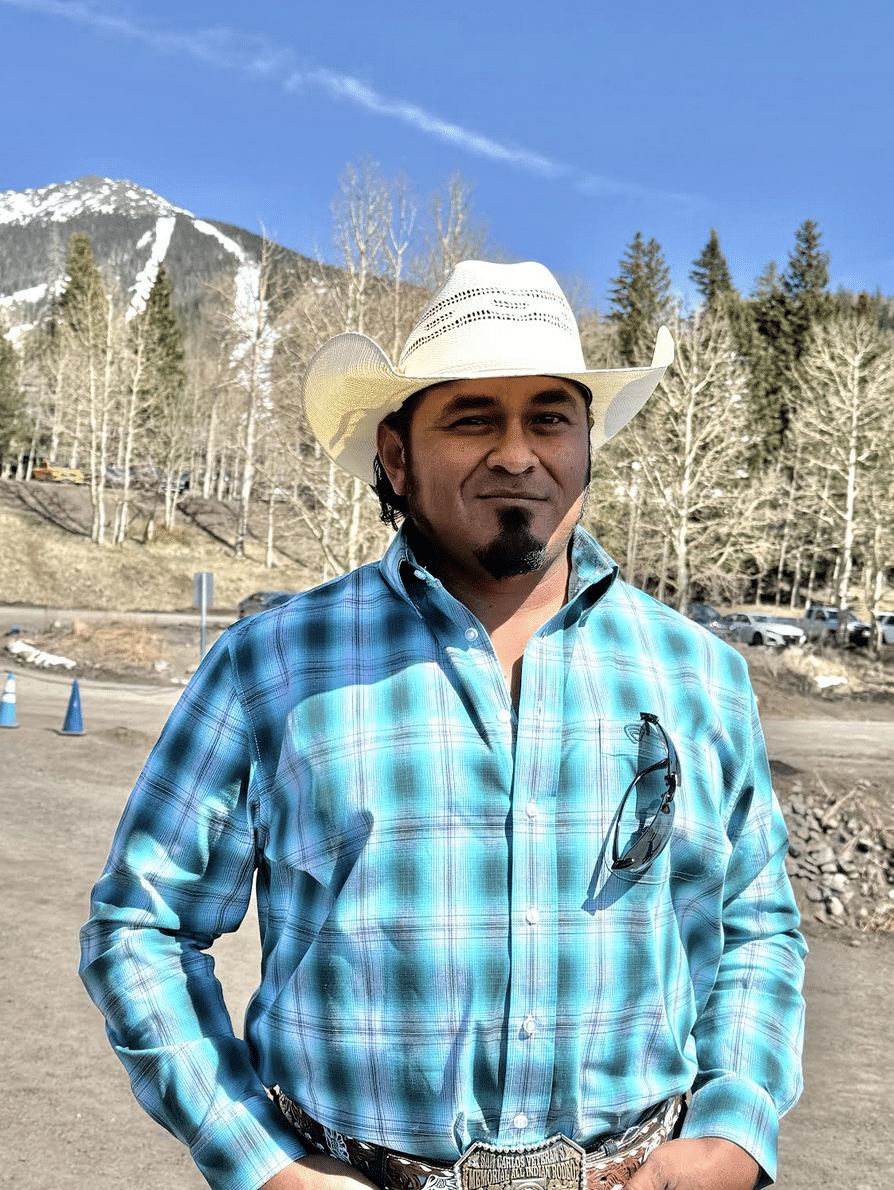

When Sisto Hernandez, Southwest Coordinator for the Western Landowners Association and a White Mountain Apache Tribal member, started working on wolf-livestock conflict years ago, “I was not happy about our reservation being again forced to shoulder the weight of another government mandate.” After being appointed to the FWS Mexican Wolf Livestock Coexistence Council, a group FWS assembled of affected communities, he started seeing things differently, and now appreciates the coexistence work.

“I still wouldn’t call myself a wolf advocate, but wolves have been re-established as part of the ecosystem and something that’s important to me is this culture that we all share—doesn’t matter if you’re Native, if you’re white, if you’re Mexican, if you’re Black—this is something we’re all part of and I don’t want to see that go away,” says Hernandez.

“It’s more important for me to find a way for all of us to be here together than to be one of those people that’s just going to pine over how things used to be.”

While the White Mountain Apache Tribe actively works on coexistence efforts, not all Tribal nations deal with wolves in the same way—there’s quite a bit of Tribal land in the region. “It’s okay if [tribes] don’t choose to allow wolves on their reservation,” says Hernandez, “but wolves are likely going to come and it’s best for their ranchers to be armed with conflict avoidance and coexistence tools in case” to help minimize loss.

“People either really love wolves or really hate wolves,” says McGee, who grew up on a ranch in Texas, went on to study wildlife biology, and has worked for USFWS since 2001. He spends a lot of time camping, hiking, and hunting in wolf country for recreation, in addition to his excursions radio-tracking wolves or introducing fostered pups.

“I consider that area where we’re doing wolf reintroductions to be kind of like my church,” he says. “I go there to get my batteries recharged, and I want to do something that makes a difference and betters my ‘church.’” And that includes ensuring others have the opportunity to hear Mexican gray wolves howling in the wilderness. He, and many other partners, are doing their part to ensure these majestic animals are here to stay, no matter the challenges.