In February 2020, Mississippi soil sodden with two months of excess rain weighed on a pipeline tucked within it. At 7:06 p.m. on the night of the 22nd, it became too much to bear. The soil slumped. A weld snapped. The pipeline pressure plummeted. The carbon dioxide that had been compressed into a fluid within exploded outward as it became a gas again. The eruption created a frosted crater 40 feet deep—the severed pipe exposed within like bone in a gash.

For eight minutes, according to an investigation by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), carbon dioxide billowed forth before the operator, Denbury Gulf Coast Pipelines, shut the safety valves. In that time, an estimated 31,405 barrels of CO2 poured out. All the while, a mile away, at the bottom of a hill, the hamlet of Satartia sat unaware of the cloud of invisible, odorless, asphyxiating gas that tumbled toward it.

Unlike oil, natural gas, and other such substances typically pumped through pipelines, carbon dioxide is inert. It’s neither flammable nor poisonous by itself. But carbon dioxide is heavy. And in large concentrations, it tends to hug the ground and displace oxygen as it spreads. Thus, by robbing the body of its most basic necessity, exposure to concentrated CO2 can cause headaches, drowsiness, disorientation, irregular heartbeats, and, in extreme cases, death.

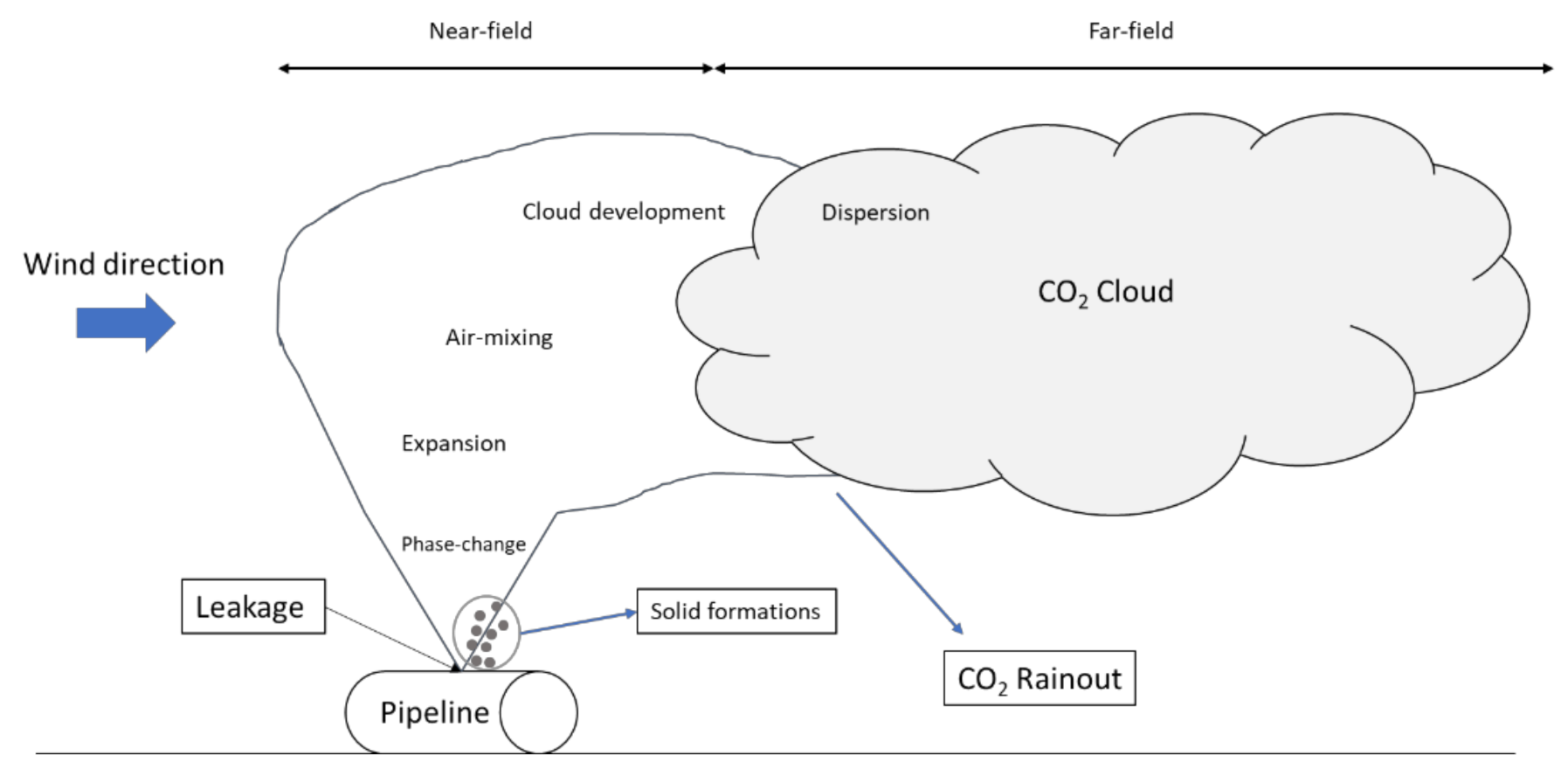

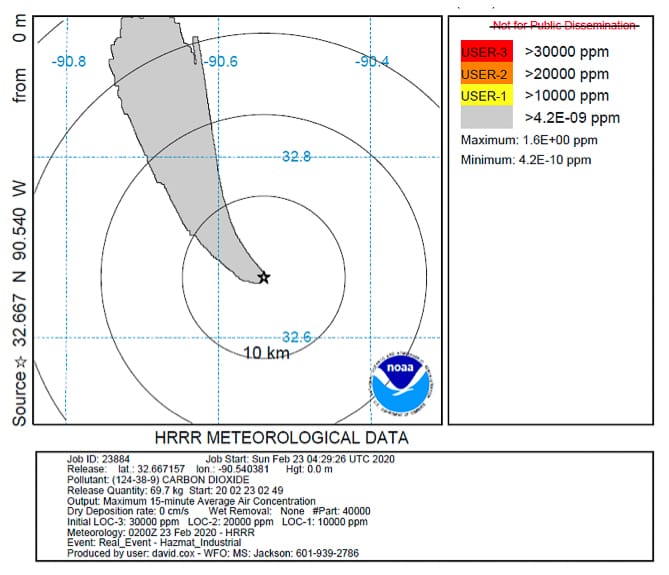

With such risks posed by potential pipeline failures, operators like Denbury, which ExxonMobil acquired in July 2023, are required to prepare for them by, among other things, training first responders in towns likely to be affected. To determine who may be impacted, operators simulate how carbon dioxide would spread after a failure and where it might go. But these failures behave in tricky ways: the liquid CO2 turns to gas, erupting outward and occasionally depositing dry ice in its wake, before dispersing. Combine that natural chaos with a complex, hilly terrain, and computer models become complicated even, at times, unreliable.

“Denbury’s model did not contemplate a release that could affect the Village of Satartia,” PHMSA’s investigation found. As a result, they did no drills with local emergency personnel.

Thankfully, first responders in Yazoo County, where Satartia is located, had conducted an unrelated drill just three and a half months earlier that prepared them for this emergency. They evacuated 200 people in the area, with 45 seeking attention at local hospitals. Though only two were said to be hospitalized a few days after the blowout.

According to a report prepared by the Center for Toxicology & Environmental Health, residents exposed to levels recorded by an investigator in one location may have suffered “mild narcotic effects.”

“To the best of CTEH’s knowledge, including several interactions with community members during this response, there were no reports of hospitalization due to loss of consciousness within the community,” the report read.

Representatives from the fossil fuel and carbon capture industries often point out that, compared to those for oil and gas, carbon dioxide pipelines are quite safe, with far fewer incidents per mile, no reported deaths, and only a single injury, which a contractor sustained in 2007 during the construction of a carbon pipeline. This is backed up by data that independent, nonprofit watchdog Pipeline Safety Trust has collected.

According to an analysis by the Great Plains Institute, there has been around one incident per year for every 1,000 miles of carbon dioxide pipeline between 2004 and 2022; this compared to roughly two incidents per year for every 1,000 miles of crude oil pipeline, according to industry data. There are however, only around 5,200 miles of carbon pipelines nationwide at the moment, compared to 228,000 miles of crude oil pipelines. Given the evacuations and hospital visits, Denbury’s failure at Satartia was arguably the most significant incident a carbon pipeline has experienced in their half-century history.

Accidents are “a reasonable concern for communities to have,” said Anna Littlefield, a PhD candidate at the Colorado School of Mines with expertise in both the science and politics of carbon capture projects. “Transporting the CO2 is the riskier part of a project.”

Still, she feels the public’s perception of that risk is to some degree exaggerated.

“Operators have a vested interest in transporting that CO2 safely, especially because, if we have an incident with a pipeline, it could take us back 10 years in terms of public acceptance,” Littlefield told Deceleration.

1. Crater created by rupture containing fallen debris, dry ice, and the failed pipe section (blue arrow is pointing at the pipeline separation). 2. The failed pipe sections shown separated by a few inches. 3. Plume model data generated by U.S. National Weather Service/NOAA indicating direction CO2 would have followed from ground level while dissipating. Satartia is withing first ring, less than two kilometers northwest of release site. All via Failure Investigation Report by Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

Since Denbury’s pipeline failure in Mississippi, industry representatives have claimed major improvements to their operating procedures, including monitoring and preventing hazards like landslides, enhancing their ability to predict CO2 flows after failure, and refining their emergency response guidelines. “Today’s operations are safer as a result,” said Michael Butler, a public affairs manager in ExxonMobil’s pipeline division, in a recent webinar. (ExxonMobil did not respond directly to Deceleration’s inquiry for this story in time for publication.)

But despite the industry self-proclaimed improvements, regulations have stayed the same. That’s a problem according to watchdogs like Pipeline Safety Trust.

“These pipelines, from a safety perspective, are under-regulated at the federal level and at the state level,” Kenneth Clarkson, communications director at Pipeline Safety Trust, told Deceleration.

Some of the shortcomings would have been addressed by a draft regulation that PHMSA published to their website in the final days of Biden’s term. The rule would have expanded regulations to cover pipelines for both liquid and gas CO2, whereas right now only supercritical carbon dioxide, a high-pressure fluid form of the substance, is covered. It also would have for the first time instituted requirements for modeling the dispersion of CO2 vapors were a failure to occur; created new CO2-specific standards for testing, material toughness, and ongoing operations and maintenance; as well as established clear criteria for converting existing infrastructure into CO2 pipelines.

But the Trump administration shelved it immediately after the inauguration, before it ever appeared for public comment. Even the mention of updating regulations for carbon pipelines disappeared from PHMSA’s unified agenda, Clarkson said, adding: “At this point in time, we don't know when that will be considered again.”

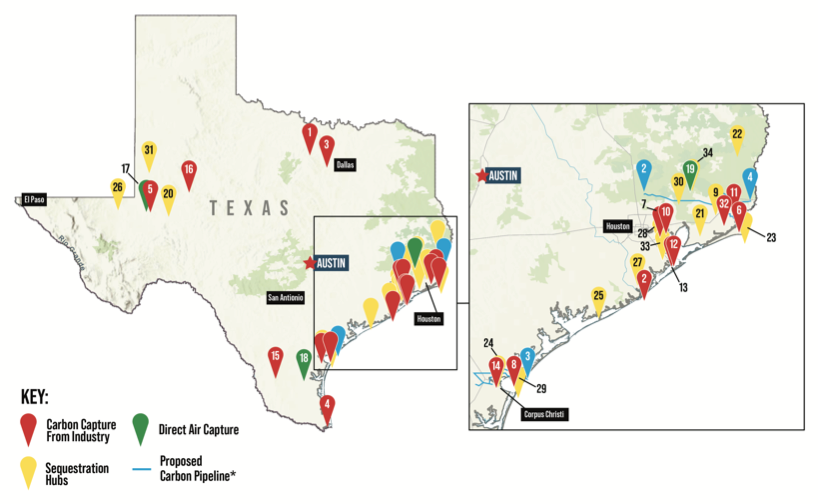

Yet we stand at an inflection point for the adolescent carbon capture industry that heralds the build out of pipelines that will transfer all the planet-warming gases captured to wells and injected miles into the Earth. Should the Trump administration not oppose the growth of the industry, tax credits for carbon capture—which were expanded under Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act and maintained under Trump’s budget reconciliation package—could, at the very least, triple the annual amount of carbon captured at power plants and industrial facilities over the next decade and a half.

That trend, combined with the growth in carbon removal schemes that seek to hoover CO2 directly from the air itself, would demand the rapid growth of a pipeline network to shuttle the substance around the country to the select few sites that meet the conditions required for long-term storage.

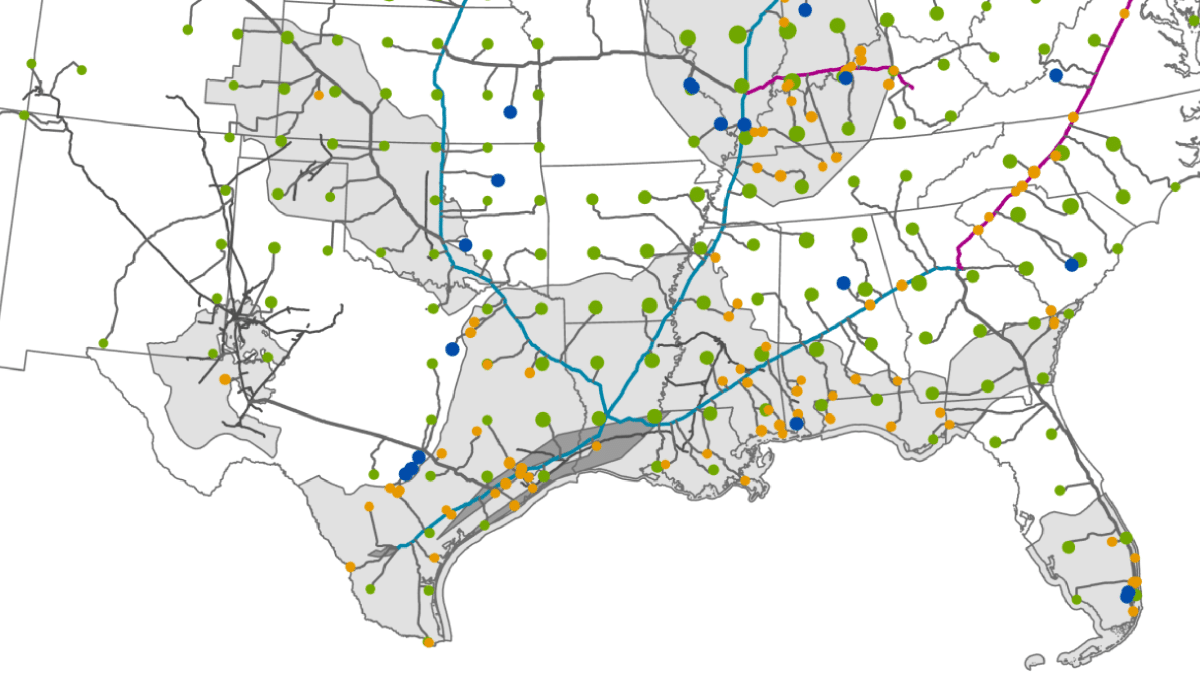

At the moment, over 5,000 miles of carbon pipelines can be found across the nation, mostly in West Texas and along the Gulf Coast. But researchers estimate that, in the decades ahead, almost 69,000 miles of these pipelines could lace the country, with rural, Black, and low-income communities the most likely sites for their construction. Many of these pipelines are also likely to end up in Texas and the other Gulf Coast states: both because of the fossil fuel industry’s immense presence in the region and because Texas is home to much of the unique subterranean geology required to permanently store carbon underground.

To ensure communities are protected against the possibility of a pipeline failure as companies ready to ramp up construction but the federal government shirks its oversight responsibilities, it falls on state governments to step up and tighten regulations. Both Butler and Littlefield said that carbon capture companies and pipeline operators have become increasingly diligent and cautious over the years and feel regulations are already quite strict. But watchdogs and community organizations remain skeptical.

“What one company says, another company doesn't do,” said Clarkson. “In order to really make our communities and people safe, you need to have regulations, and then also enforcement.”

Clarkson and his Pipeline Safety Trust colleagues feel that the bill recently signed into law by California Governor Gavin Newsom is a great example of the steps that states can take to help protect the communities within their own borders—even if they feel that it doesn’t quite go far enough. The new law prohibits the conversion of existing pipelines, requires operators to draw up in-depth emergency response plans, and sets strict criteria for a pipeline to meet if it passes within two miles of schools, community centers, healthcare facilities, and private residences. Still, Pipeline Safety Trust would have liked to see the law include a clear limit for contaminants like water, which can mix with the CO2 to form an acid that eats through steel.

These safeguards are increasingly necessary as the world chases climate goals that flitter further away each year as the fossil fuel phaseout stalls and other emissions reductions lag. While carbon capture was not explicitly on the agenda during the recent UN climate negotiations, according to the Global CCS Institute, the carbon capture and carbon removal technologies are integral to the net-zero pathways envisioned by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

While many would love to see nature-based carbon removal strategies prioritized, ecosystems can only accomplish so much, and they function at a fundamentally different scale from what humanity has emitted through its consumption of fossil fuels.

“CCS is one of the only technologies that stores the volumes [of CO2] that we need to store,” Littlefield said. “It's not the elegant nature-based solution. This is the brute force option, but unfortunately, we need the brute force option.”

The heavy industries that emerged and swelled in the past few centuries have dredged up carbon that the planet had tucked away for millions upon millions of years. And although it may offend many people’s affinities for the elegance of nature, the only way to ensure that this planet-wide pollutant doesn’t continue to raise Earth’s temperature is to put the carbon back where it came from: deep underground. That will require new industries to grow and mature, which will also, unfortunately, necessitate thousands of miles of new pipelines to spread like a web across the country.

Already, a company in the Midwest, Summit Carbon Solutions, has attempted to use eminent domain lawsuits to compel farmers and landowners to give up portions of their property, so it could route portions of a 2,500-mile pipeline through their fields. But ultimately, a cross-cultural movement of Indigenous activists and white farmers in South Dakota and surrounding states have mounted a successful effort to block such seizures.

If nothing else, their efforts demonstrate that so long as regulators are slow to establish and enforce laws that offer meaningful protections to communities, people have the power and potential to rally together and block these pipelines.