The thing about this moment is that, basically, everyone is incredibly disorganized. However, that means that you, literally any random person, can just take the things you know how to do and start organizing. The system is designed to make sure that you don’t do that. … They are fucking terrified of this.

—Mia Wong, It Could Happen Here

In November, right after the 2024 election, Deceleration began a series of informal gatherings—house meetings—to bone up on the skills and internal dispositions we would need to survive and fight in the years to come. To “prepare to protect,” to reference the title of a new series we’ve launched.

In doing so, we were inspired by an initially ad hoc group called Choose Democracy, whose email list I’d signed up for a few years back, in the lead up to the pandemic-wracked 2020 election and subsequent, poisonous cage rattling about stopping “the steal.” In October 2020, Choose Democracy led online trainings that I attended alongside what seemed like thousands of others on how to prevent a coup.

The main takeaway I recall was the importance of getting the political center on the side of the grassroots, forming temporary and strategic alliances with those in a position to deny legitimacy or refuse to obey. In the unsettling interregnum between election and inauguration—punctuated, of course, by the actual attempted coup of January 6, 2021—Choose Democracy would also send out regular coup-o-meter alerts (which, by the way, resumed posting updates in February 2025, in the wake of DOGE’s slash-and-burn romp through the internal workings of the federal government, which Choose Democracy describes as an administrative coup).

More recently, in the months before the 2024 election, they piloted a new resource—a choose-your-own-adventure book and website called What if Trump (or Biden) Wins? Developed by former 350.org organizer Daniel Hunter, the goal was to help folks scenario plan, anticipating various electoral outcomes and thinking through how they might respond based on their capacities, desires, and needs.

Shortly thereafter came the 2024 election itself, followed by an eerie hush. We republished Hunter’s piece on how to prepare ourselves (here’s a series of video shorts if you’re tired of compulsively consuming written commentary.) And I went back to the training materials Hunter and others had developed, based on historical research on the best practices for resisting autocratic governments from global people’s movements, a community version of the scenario planning activities published earlier in book form. Before the election, it had felt like there wasn’t enough time to do something like study and plan. After, it felt like anything other than studying and planning was useless. The deep sense of quiet, the lack of response, was as unsettling as the escalating agitation in the weeks before J6.

People were frozen, I knew that. It wasn’t the stunned shock of 2016; this time around, it was exhaustion. But it also felt like people were thinking. What we’d done before hadn’t worked. What would? No one knew. Yet. No one knew yet. It felt important to get together and think it through, together.

Robert Evans, one of the hosts of the anarchist podcast It Could Happen Here, hit on a similar awakening. In an episode from January 20 called “The Age of Cowards and What Happens Next,” he said:

“The larger solutions to our common woes, if they ever arrive, will be something new—something we haven’t tried yet. I feel very confident that they won’t take the form of another march, or involve everyone finally agreeing to be the same kind of communist or anarchist or whatever. … Shit can be different. But not unless you’re willing to try different shit.”

So after the election, we started meeting every week or two to go over Choose Democracy’s trainings. We didn’t put it on the Deceleration website. We didn’t put it on social media. People were already texting each other, emailing each other, checking in—so we invited them all over on a Saturday morning. The first few times we hosted; then other folks in the group began to host and facilitate. We tried to get through as many of the trainings as we could before the inauguration, knowing we needed the information. None of us had been trained in advance; we were learning by doing, learning by facilitating a collective process of learning.

Our first gathering, held a week after the election, was the biggest—about 20 people, plus dogs and cats, crammed into an improvisational circle in our living room. We supplied tacos and coffee and tea; other folks brought flowers, fruit, pan dulce, champurrado. Kids camped out with tablets and art supplies under blanket forts. Mostly at that point we just needed to be together in person. Over time, as we dove into the trainings, numbers dwindled until we ended up with a core study group of about seven or eight, though they swelled again for one particular two-part training on how to talk with people we might disagree with. We would start each gathering by checking in, seeing if people or their families and communities needed any specific kind of support or had resources to offer others, writing responses on giant paper sticky notes on the wall for reflection and access.

We got through six trainings before the inauguration, with a seventh and final one currently being planned.

For those who may want to replicate these efforts within your own networks, here’s the curriculum we followed:

- Regroup to Fight Back

- Group Scenario Planning

- Strategic Escalation in a Trump Era

- Action Security and De-Escalation

- How to Talk to People You Might Disagree With

- Harnessing Our Power to End Political Violence

- Mutual Aid 101

For me, one of the biggest takeaways from these sessions has to do with the unique nature of fascism, and how that shifts both the tactics and internal dispositions required to defeat it. We’re used to organizing under conditions of neoliberal democracy, in which private and corporate interests prevent popular access to actual political decision-making—usually in ways that are deeply racialized and gendered—which nonetheless still make a claim to being inclusive.

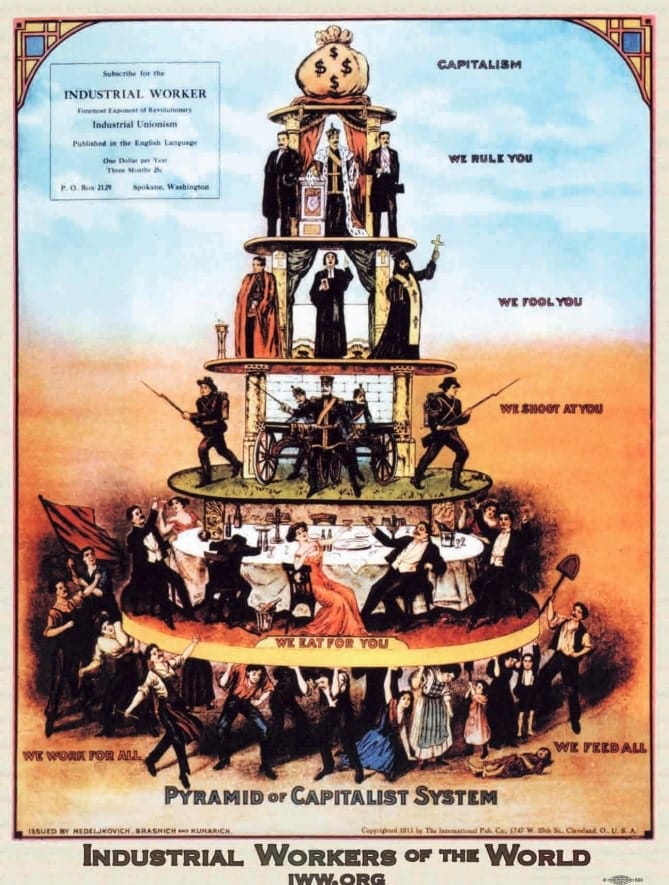

We’re also used to thinking of power as a pyramid, as in the famous IWW tower of capitalism:

At the top of this pyramid model are the 1 percent, as popularized by Occupy, the oligarchs and bosses whose original theft of Native land, Black lives, and the labor of all workers became the basis for their power. Below them are the elected officials who claim to represent us, but who more often than not do the bidding of the bosses. And at the bottom are the 99%, the masses organizing to build a visibly mass movement for better working conditions or neighborhoods.

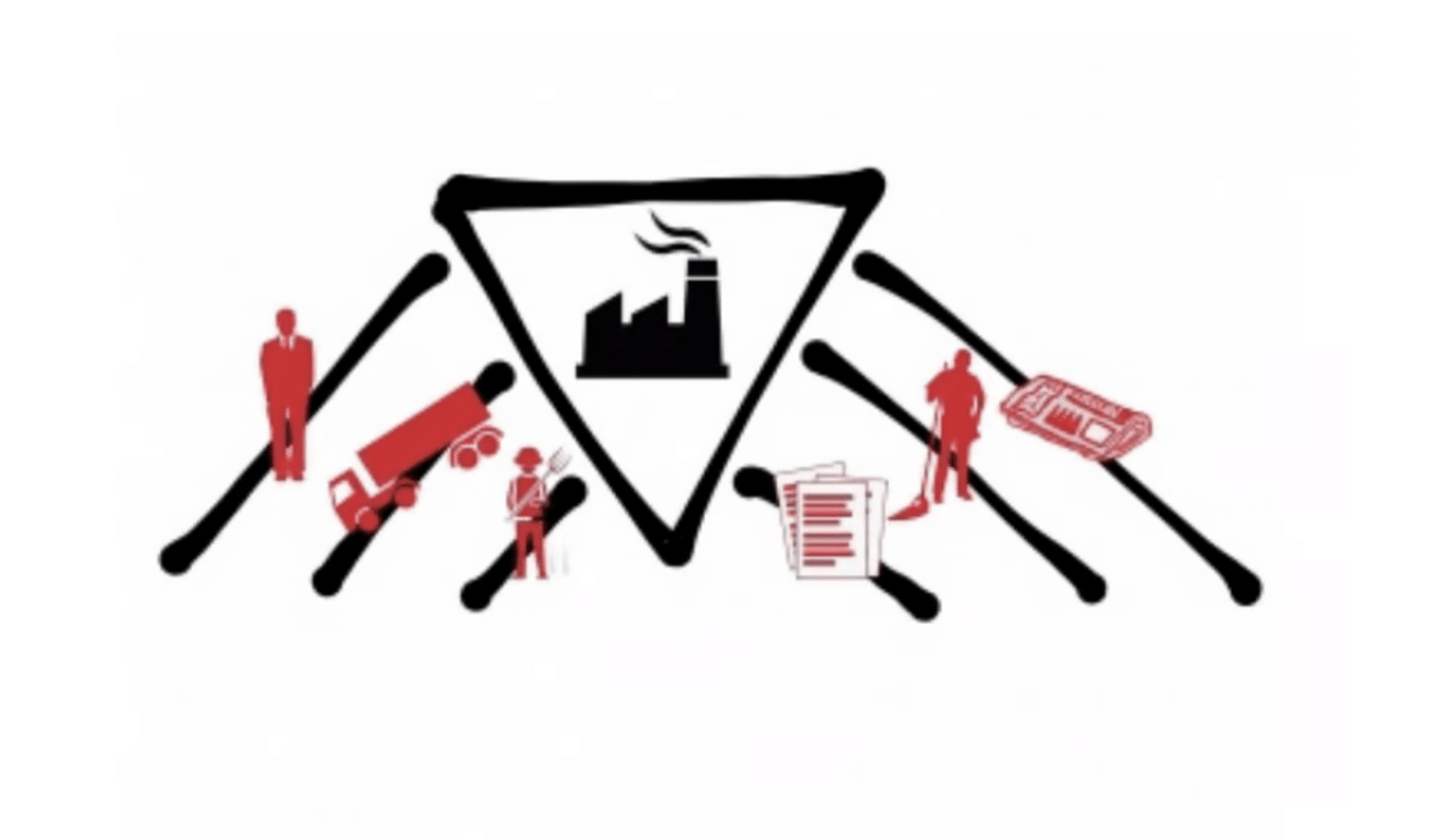

It’s still a very useful model for thinking about capitalism and its neoliberal forms of governance. But an autocracy, as Hunter explains, is better understood as an upside down triangle, held aloft on its pinnacle by pillars of institutional power—local government, media outlets, shareholders, policymakers, organized religion, the military. (Newsletter subscribers, you may recall that Greg detailed this point back in mid-November.)

Moreover, our tactics of necessity shift given that autocracy means dissent becomes increasingly repressed and punished, shrinking the space for public contestation.

While we cannot cede our right to public demonstration, a lot of our organizing energy under autocracy necessarily happens offline, quietly, in living rooms and other informal spaces. Much of it takes place via affinity groups, small networks of trusted friends, family, and neighbors, versus large organizations.

Much of it looks like mutual aid, organizing to protect the most vulnerable, instead of lobbying or attempting to persuade those in power.

At our last gathering on political violence, I finally hit on what this shift in tactics might look like in practice. Take climate as one example. Under neoliberal Dems either federally or locally we would rally, hoping mass turnout might push them harder than powerful development interests. But under a federal and state government now actively hostile to climate action, creating a phone tree of neighbors—so that in a heatwave or freeze or other climate disaster you have a rapid response network in place—becomes much more important than getting people to arrive at a particular position or analysis so that they’re moved to sign a petition, call their representative or speak at a public hearing.

What takes priority is relationship, a network of care, and not necessarily agreement or ideological consistency. When a crisis does arise, and we know it will, we know who our neighbors are and that we will act to protect one other—important actions that can help those most targeted and abandoned by the state.

Hunter identifies three other critical roles we must collectively fill in addition to protecting the most vulnerable: defending civic institutions (elections, the judiciary, federal departments); building alternative and parallel institutions; and disrupting and disobeying. Mass movement building is thus still important. But its tactics must be more than symbolic marches or rallies; they must actually disrupt fascist organizing and takeover.

Toward that end, Hunter urges us to ask ourselves: which of the four roles do we gravitate toward, either out of capacity or desire or necessity?

As in 2020’s trainings on averting a coup, a big part of the tactics here involve getting the political center to stand with the grassroots. This can feel counterintuitive within the historical context of neoliberal governance, where we’ve often had to fight with City Council as hard as we’ve fought against developers or corporations. It makes sense we would feel betrayed by corporate Dems who have accelerated fascist takeover in their abandonment of working class and poor people at home and support for genocide and war crimes abroad. But we’re in a very different political ecology now.

Neoliberal governance as we’ve known it is crumbling, but not in a good way; it’s being replaced by naked oligarchy, monarchism, and theocracy, a totalizing privatization that seeks to demolish even the lip service of a public interest or common good.

What researchers on people’s movements have seen is that the most successful struggles against strongmen like Musk, Trump, and Vance are those in which the institutional pillars join up with social movements. To put it more directly, we need those inside institutions to refuse to cooperate. We don’t need to share an analysis on all things. But we need people on the inside not to abandon those being most violently scapegoated—migrants, trans people—in this moment. We need those on the inside not to roll over and comply.

For as we learned together at our house meetings, autocracy is ultimately fragile. The upside down triangle may appear all-powerful and stable, but this is only because it’s held up by institutional pillars in turn filled with people who can choose to either cower in fear (as have many university administrators in Texas public universities) or loudly refuse to obey (as a growing number of elected leaders and judges have, thanks to enormous public pressure). Remove enough of those pillars and the structure topples.

I heard this same idea, on the fragility of fascist strongman, echoed by Mia Wong recently on another recent episode of It Could Happen Here. I played it for a high school student who is consumed with rage by Trump’s victory, by the political landscape he has inherited on the cusp of adulthood. I wanted him to hear what Wong had to say, because it had given me—not hope, but optimism? The sort of pragmatic optimism Octavia Butler champions in her Afrofuturist cli-fi novel Parable of the Sower, which insists that we must squarely face the reality of collapse so that we can act collectively to build the society we need.

Here, I’ll play Wong’s words for you too:

Do you think these people can hold 330 million people in line by sheer force? No. Of course not. There’s no fucking way. … This is a strategy that is built around getting your compliance. And if they can’t get your compliance by you agreeing with them, they’re going to attempt to get your compliance by just taking you out of the equation, right? They need you scared, they need you confused, they need you completely convinced of your own helplessness.

They need you to forget that, as the old song [“Solidarity Forever”] says:

“In your hands is placed a power greater than their hoarded gold, greater than the might of armies, magnified a thousand fold.”

They need you to forget the next line of the song! Which goes:

“We can bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old…for the union makes us strong.”

If these people were actually strong, they would not need an entire strategy based around political demobilization!

People are coming out of their freeze. Students are walking out of class. Local electeds are issuing statements. People are holding house meetings. They’re thinking about what they can do, what they want to do, what they need to do. They’re thinking and they’re studying and they’re reading and they’re planning.

But more importantly, they’re getting together.