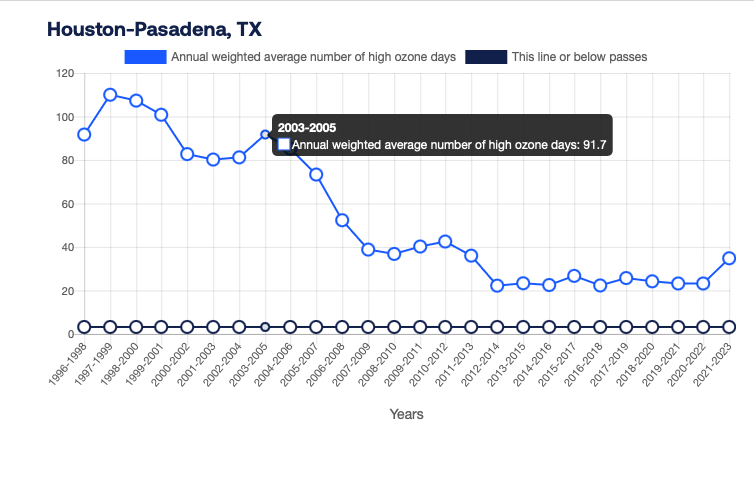

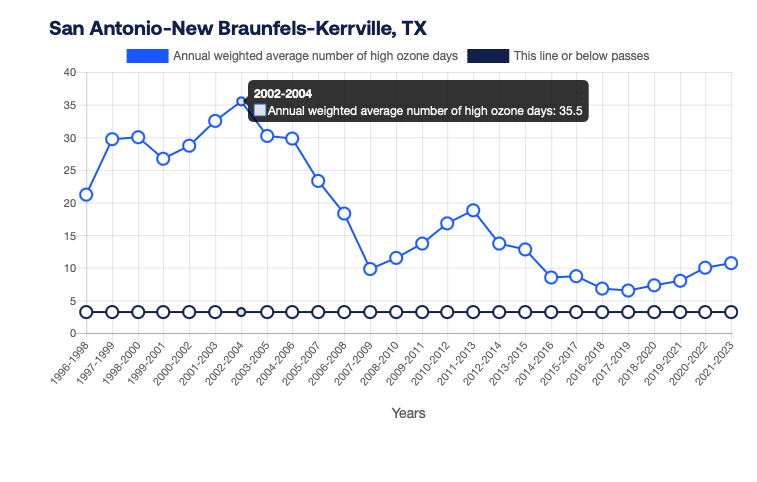

Earlier this year, the American Lung Association (again) included San Antonio, Texas, among the worst U.S. cities for its air quality. Today, the area remains in “serious nonattainment” with federal air quality standards.

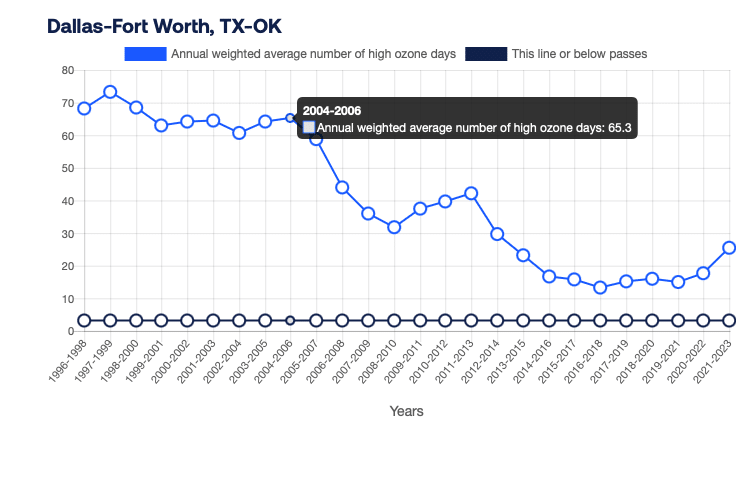

As with the Dallas-Forth Worth metroplex and greater Houston, also out of compliance with federal standards, San Antonio’s ozone pollution has improved compared to a 20 years ago. But the science of public health has also improved over the years—and along with that tightening standards over what constitutes unhealthy air.

Ground-level ozone known to punish asthma sufferers, while increasing heart attacks and premature deaths, is created when hot weather cooks pollutants—such as volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides—that are released by heavy industry and gas-powered transportation. Currently roughly half of all people living in the United States (about 146M) are considered to be living in areas with what the ALA calls “unhealthy levels of air pollution.”

Federal and state officials following the lead of President Donald Trump, however, have thrown past climate and public health progress into reverse in recent months. Still, a small panel of experts in the fields of public health, clean energy, and public policy gathered in San Antonio on Thursday, October 2, 2025, to call for continuing to pursue renewable energy for the sake of community health. Their comments were made during panel titled “Investing in Health in San Antonio, Texas: The Local Impact of Climate Action and Clean Energy” that was hosted by the nonprofit Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments.

Members highlighted local progress for cleaner energy systems to inform and grow support among public health officials—nurses, in particular—for future investments in cleaner energy, community gardens, and proactive policies that reduce urban heat impacts.

Introductions were punctuated by applause over the reminder of the City of San Antonio’s 2023 commitment to install 13MW of solar at dozens of municipal sites—“that will be the largest such installation in Texas and second only to NYC nationally,” said panel moderator Milagros Elia of the Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments.

Doug Melnick, San Antonio’s assistant director of resilience and sustainability, (a recent merging of the City’s Office of Sustainability and Office of Resilience) said the $30M investment was made possible by the support of the former Biden Administration and passage of the monumental Inflation Reduction Act.

“Every corner of the city, every city council district is going to have some onsite solar that’s going to reduce the demand on the CPS [electrical] grid—[and offset] anywhere from 50 to 80 percent of these building’s loads,” Melnick said.

While recognizing the national conversation about renewable energy systems has shifted, Melnick described the sola project as a “once in a lifetime opportunity” for himself and his staff. The project will be paid off within 10 years, he said, while the solar panels themselves will have another 10 years of reliable life remaining—essentially providing free power to the city for those remaining years.

“For every dollar we spend on our projects, we get 40 cents back,” Melnick said. “We’re up to 54 buildings.”

The expansion of wind and solar projects in recent years kept San Antonio’s city-owned CPS Energy from failing grade on the recent Sierra Club utility survey. The annual Dirty Truth report highlights the progress (in the case of LCRA and others, lack thereof) of utilities moving from dirtier energy sources to renewable systems.

The city’s decentralized solar efforts have a side benefit for grid security in a time of rising climate-driven storms, Melnick said.

“The key to resilience is having multiple contingencies in place. As we saw during [2021’s winter storm] Uri, natural gas is not necessarily the most reliable fuel,” he said.

However, all is not sunny in San Antonio, as those high ozone days confirm. Overshadowing that investment have been pressures from state and federal government demanding a ballooning of dirtier power investments to facilitate rocketing AI and data center buildout, including keeping some dirty power plants burning longer in the name of grid reliability, new gas unit purchases, and a string of backup diesel generators required by the state grid operator but decried by community members during a recent South San Antonio “toxic tour.”

DeeDee Belmares, a climate organizer with the nonprofit Public Citizen, said cleaner solar and wind energy investments are critical because many of the city’s most vulnerable residents are already subjected to more than their share of pollution from dirty power plants on the city’s South Side.

“We don’t want people breathing in the emissions that come from gas facilities, like sulfur dioxide, particulate matter,” Belmares said. “Mercury coming from coal plants: I don’t have to tell the public health officials why those emissions are bad.”

She added:

“We have senior citizens, we have children, we have people with disabilities, we have those with health issues, we also have high rates of poverty. So investing in clean energy is the best way to take out those things that are causing resperatory illness, for example. We all want our children to grow up in a healthy loving home.”

For her part, Adelita Cantu, a health professor and interim director of the PhD program at UT Health School of Nursing, said her role as a teacher of nursing is to bring awareness of the interplay between energy and the environment and public health.

“It’s very important to future nurses to understand that clean energy is so important to sustain the health of a community,” Cantu said. “By reducing emissions you are able to go outside and play, you are able to breathe freely on these days where you might otherwise have ground-level ozone. You don’t have to be fearful of being outdoors and being afraid of having these exasperations of your conditions.”

Good policy around energy and public health means helping keep people safe and healthy without unnecessary medications.

“It’s not just giving someone a pill,” she said. “It’s a broader issue of taking care of our environment because our environment will take care of people.”

Gardening is a community health response gaining popularity across the city, added Pressanna Jose Parackal, a hospital supervisor at University Health System. Gardening participants discuss improved diets, stress reduction, and increased social satisfaction, she said.

“The staff can go and have a break, a wellness break,” said Parackal. “We saw the staff become rejuvenated, recharged. There is something to talk about. It became a wide wide social reformation happen.”

Gardens, of course, also have a cooling influence in a downtown area already racked by rising temperatures, due to reduced greenspace and heavy use of heat-trapping asphalt and concrete. Reducing that heat is a priority of the South San Heat Resilient Project, for example, an effort to improve the lives of communities on the south side of San Antonio that are already burdened from high temperatures, poor home weatherization, energy insecurity, and lack of access to healthy food, Belmares stressed.

But that South San effort has involved the opposite of top-down municipal planning processes. It represents instead a bottom-up partnership flip highlighted in recent Deceleration reporting about climate resilience efforts pushing ahead in spite of federal animosity to clean energy efforts and climate action.

“One of the things I’ve learned over the years is there’s limitations to what government can accomplish,” said Melnick. “There are times we don’t see what is already happening on the ground.

“At the end of the day I think local government, not all forms of government, we kind of think we’re the experts and we know better than others. But if we don’t take the time to ask and listen and sort of give up some of that power we’re just going to be stuck in a cycle.”

During audience questions, Bill Barker, a former city employee in the sustainability and transportation sectors, said his recent research has revealed that the City of Austin has three times the number of public water fountains when compared to the City of San Antonio.

It was news, but not a surprise, perhaps, to panelists who were are well acquainted with the deep inequities across the city. It was yet another reminder of the still looming challenges in San Antonio and across the state and world as heat and climate disasters continue to gather.

But it also has, at least conceptually, a simple answer.

“At the end of the day, no matter where you are in the city there should be some place you can go to get water,” said Melnick.