Sleek, spotted, and sinuous, the male jaguar known as El Jefe, “the boss,” roamed through the Santa Rita mountains of southeastern Arizona, captured on wildlife camera traps more than 100 times between 2011 and 2015. The last known video showed El Jefe strolling by a slow-moving stream. And then he disappeared.

Was he killed? Did he die of natural causes? Or did he just migrate away from the prying eyes of cameras? Six years after his last appearance, a camera trap in Sonora, Mexico, snapped a photo of El Jefe—120 miles south of his last location. The nonprofit Northern Jaguar Project confirmed a 100 percent match of the animal’s rosette pattern.

El Jefe’s rediscovery sent shockwaves through the conservation community. The vast distances traveled by this dispersing male jaguar emphasized the urgent need not just for binational cooperation but also for keeping borderland ecosystems open for wildlife, including jaguars, ocelots, jaguarundis, black bear, who have never known such boundaries.

“The [border] wall is going to interrupt those movements of our relatives,” says Christopher Basaldú, co-founder of the South Texas Environmental Justice Network and a member of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas.

“Just because they’re another species doesn’t mean that they should have less of an inherent right to move across their homeland.”

This month, the second Trump administration approved its first new contract for border barriers—7 miles in Texas at a cost of $70M*. Vice President J.D. Vance said in March that the president wants to complete the entire southern border wall by 2029. President Biden paused border wall construction for a time, but resumed construction of limited portions in Arizona and Texas, claiming at the time it was a requirement of the original 2019 appropriation.

“The propaganda around the wall is that the wall is stopping an invasion of people,” said Basaldú. “The people who want the wall think that it’s going to protect people in America and give everybody a beautiful life. Well, it’s not. It’s a waste of money, but it’s also a land grab.”

With the rapid-fire crises coming from the Trump administration attacking human rights, environmental protections, and the bedrock of American democracy, it’s understandable that endangered wildlife have not been front and center. However, to some people, and particularly indigenous cultures, humans are not separate from or more important than the animals and habitats we share planet Earth with.

“It’s not just the land that’s broken. It’s our relationship to the land,” Potawatomi author Robin Wall Kimmerer elucidates in her bestselling book Braiding Sweetgrass, “In the settler mind, land is property, real estate capital, or natural resources. But to our people, it was everything: identity, our connection to our ancestors, the home of our non-human kinfolk, our pharmacy, our library, the source of all that sustained us.”

Jaguars: Rulers of the Night

The Mayans believe that when the sun slips beyond view, it turns into a jaguar, ruler of the night and the underworld. The Tohono O’odham, people of the Sonoran Desert where El Jefe roams, see jaguars as protectors of their people and the environment.

The largest wildcat in North America and third largest in the world, jaguars are solitary wildcats found in Central and South America and, formerly, throughout the American southwest. They have an all-black form which some people call black panthers. Out of fear and loathing, Americans poisoned and trapped jaguars to the point they were believed extinct in the U.S.—that is, until 1996 when hunting dogs cornered one in a tree in southern New Mexico’s Peloncillo Mountains. Wonderstruck, the hunter chose his camera instead of his gun.

In the U.S., jaguars are listed as a federally endangered species. The last known jaguar in Texas was killed in 1948. But after their “rediscovery” in 1996, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) refused to designate critical habitat—areas deemed essential for a species’ recovery—something required by the Endangered Species Act.

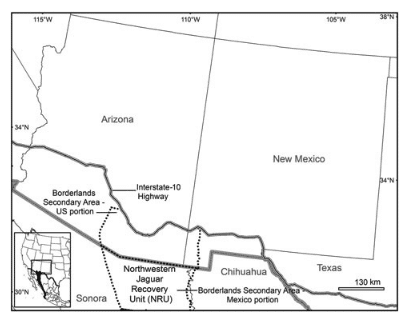

Defenders of Wildlife sued USFWS and won, forcing the agency’s hand. So in 2014, USFWS finally designated jaguar critical habitat as the ‘Sky Islands’ of Arizona and New Mexico south of Interstate 10.

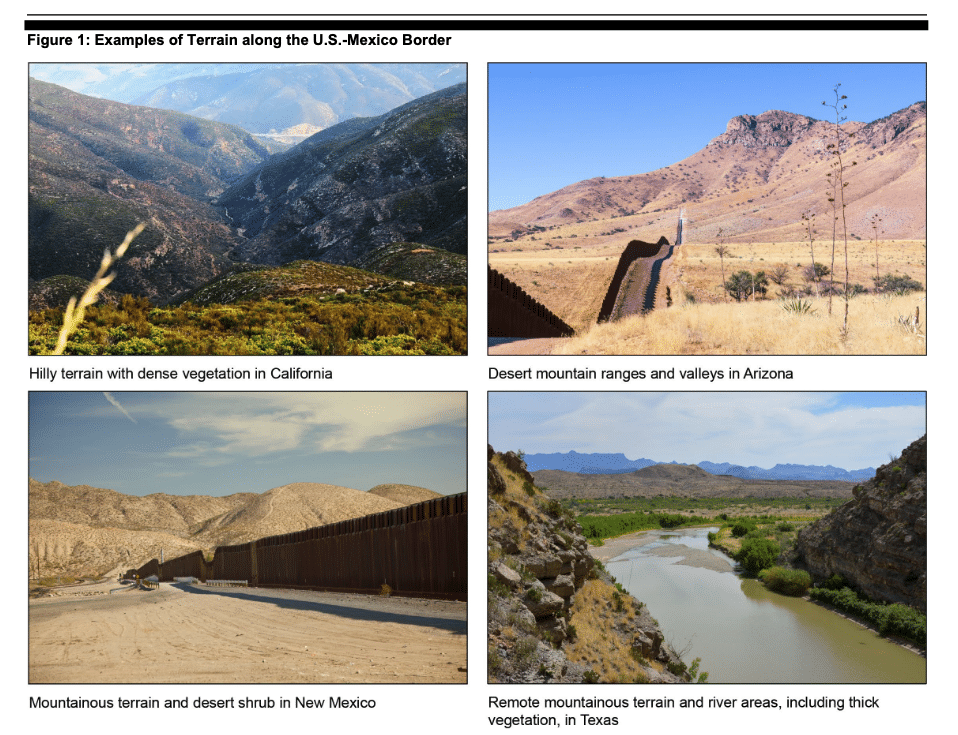

In this Madrean Archipelago, which includes northwestern Mexico and southwestern U.S., tall mountains rise dramatically from the surrounding lowlands, surrounded by a sea of desert. The mountaintops have become known as ‘sky islands’. Their wetter, cooler climate results in more forest cover than the desert below, including both coniferous and pine-oak woodland, depending on elevation. Sky islands boast incredible biodiversity: more than 7,000 plant and animal species. They’re essential for jaguars, but constantly under threat by commercial mining, logging, and development.

Beyond Borders

By the looks of it, the breeding population of more than 100 jaguars in Mexico are actively trying to find habitat north of the border. Scientists have used their unique spot or rosette patterns to identify at least eight jaguars in Arizona and New Mexico since 1996, most likely males dispersing north, although one cannot rule out the existence of a female.

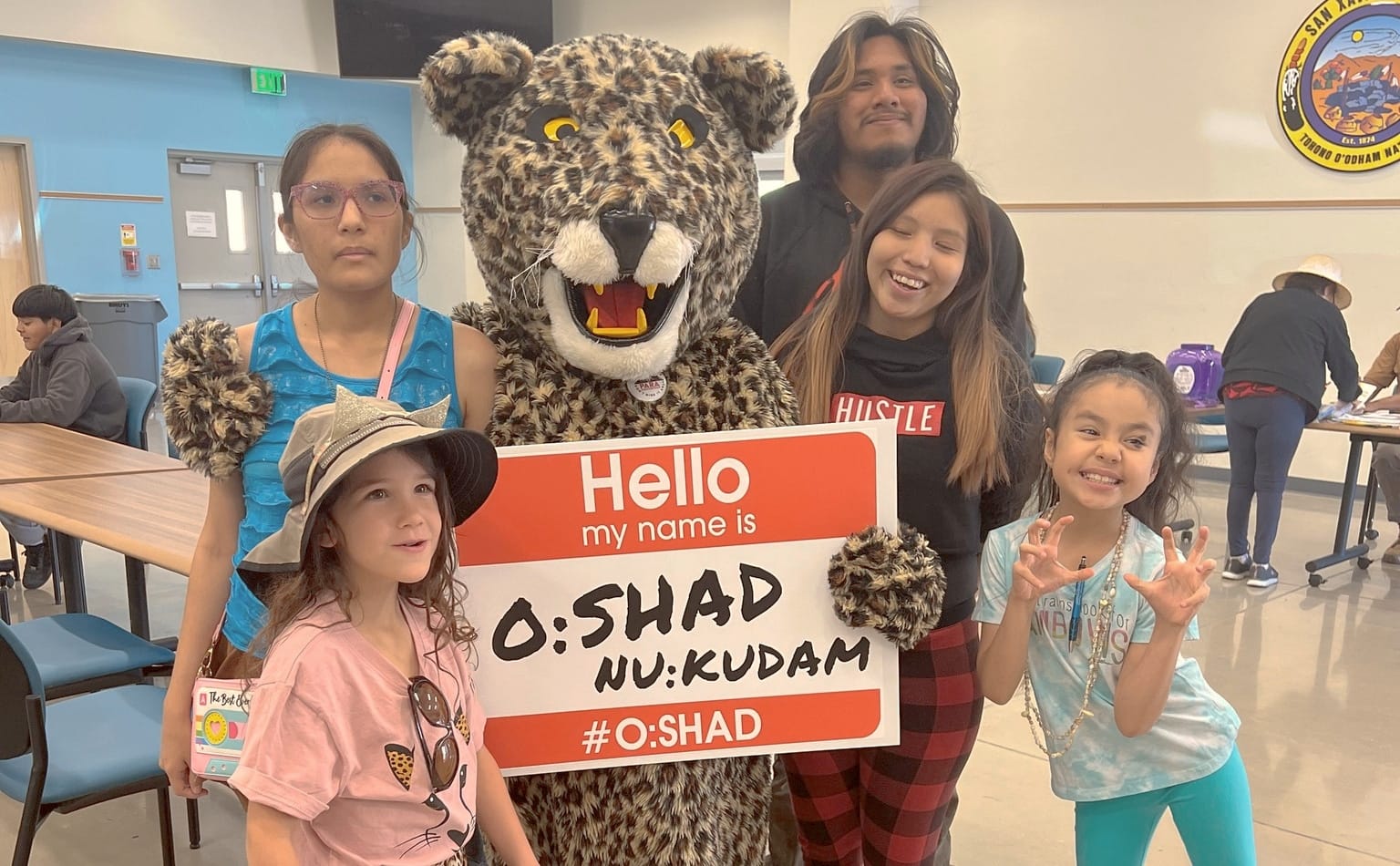

On Earth Day 2024, Tohono O’odham schoolchildren, along with kids and adults of the Pascua Yaqui and Diné (Navajo) nations, gathered to name one of these jaguars who had roamed through southern Arizona since 2023. They chose O:ṣhad Ñu:kudam (Oh-sha-dt Noo-koo-dum), which means jaguar protector in the O’odham language. In an interview with the Arizona Republic at the time, Austin Nunez, the San Xavier District of the Tohono O’odham Nation’s Chairman, said:

“We respect them. We don’t hunt them. … They’re more afraid of us than we are of them.”

A few years earlier, in 2017, Pascual Yaqui high school students named a different jaguar wandering southern Arizona’s Huachuca Mountains Yo’oko Nahsuareo, which means “jaguar warrior” in the Yaqui language. But in 2022, a jaguar pelt was seen in a photograph that scientists matched to Yo’oko’s spot pattern. A trapper had captured the cat in Sonora, Mexico, most likely an incidental take as he tried to catch mountain lions, which are legal to hunt and trap. The Northern Jaguar Project, the Center for Biological Diversity, and the Sky Island Alliance held a memorial to honor the majestic creature at a Tucson brew pub.

For thousands of years, these wildcats have freely roamed back and forth across the continent not seeing national borders. And if there’s any chance for jaguars to repopulate their original habitat in the southern U.S. and re-establish a healthy breeding population with enough genetic diversity, cross-border movements must continue.

Translocating Jaguars

A 2021 study found that the 20 million acres of montane forests north of Interstate 10 in both New Mexico and Arizona could support a breeding population of 69 to 100 jaguars. However, even without a completed border wall, the six-lane I-10 freeway—plus inhospitable habitat, including commercial development and ranchlands with little protective cover—create barriers preventing jaguars from reaching and recolonizing the northern habitat on their own.

There’s also constant pressure to mine in USFWS-designated critical habitat, particularly in the mountains along the border. The proposed Rosemont copper mine in the Santa Rita mountains, where El Jefe once roamed, was stopped through litigation, but the same Canadian company shifted to the even bigger Copper World Complex.

This January, Arizona issued its air quality permit. The Center for Biological Diversity filed a legal appeal, but bulldozers have started clearing ground. With the President’s executive order declaring a “national energy emergency,” mining and energy development will likely expand—even public lands are at risk.

Since jaguars can’t teach the northern sky islands in northern Arizona and New Mexico without help, conservationists on both sides of the border have expressed interest in translocating animals from Mexico, with some reservations. (USFWS denied a petition to reintroduce jaguars in New Mexico’s Gila National Forest in January 2024).

“We want to be mindful that this doesn’t evolve into ‘Let’s capture a bunch of jaguars in Sonora and ship them to Arizona [or New Mexico]’ while at the same time the United States is building a border wall separating our countries,” says Juan Carlos Bravo, associate director for the Wildlands Network.

“If there’s recognition that [parts] of this wall need to either remain open or come down so that corridors are maintained, and [jaguars are] brought into the United States without impacting source populations, I’d be supportive of that initiative.”

In his work with Wildlands Network, Bravo facilitates the Jaguar Pathway to Recovery project that aims to protect habitat corridors so jaguars can move between Sonora and Arizona. Before that, he helped create the Northern Jaguar Project’s Viviendo con Felinos (Living with Felines) program in Sonora, where jaguar habitat is mostly private ranchlands.

“We’re trying to foster appreciation of wildlife [by] bringing in additional income to these places,” says Bravo. Mexican ranchers can place camera traps on their lands and receive payments for photos: $250 for a jaguar, $75 for an ocelot, $50 for a mountain lion, and $25 for a bobcat. “To the extent that they make sure that the [cats] are protected, they’re more likely to get incentives.” This innovative program may prevent other cats from suffering Yo’oko’s fate.

A Blockade to Wildlife

Since 1996, the government has had authority to construct border wall without following certain environmental laws (e.g. the Endangered Species Act and National Environmental Policy Act), but these waivers were used judiciously. That changed with the passage of the REAL ID Act of 2005, which widened the waiver authority to include all state and federal environmental, cultural, and land management regulations and the Administrative Procedures Act, which require a detailed analysis of a proposed action’s impacts. Waivers of laws have occurred under every President since George W. Bush, but 84 percent of these —including the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act—were during the Trump administration. This means the government can destroy habitats as they build with nary a concern to flora, fauna, or ecosystem—and with no requirement to restore damaged lands and habitats afterward.

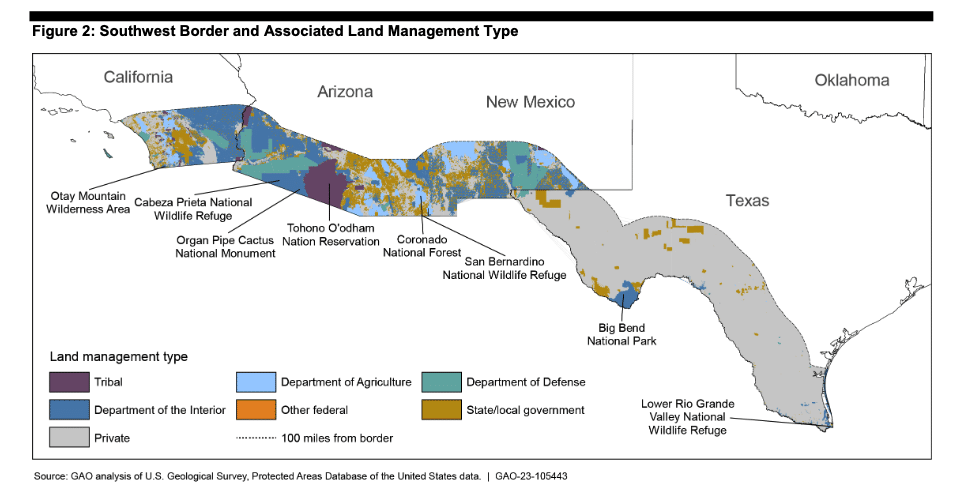

Due to steep topography, portions of the border remain open in Arizona and New Mexico, but that could change if Trump proceeds as planned. As of 2023, 741 miles of the entire 1,950-mile border (38 percent) was fenced, per a U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO) report. During his first term, Trump extended the border wall by 87 miles at a cost of $15 billion; this included replacing 282 miles of vehicle barrier—short enough to allow animals and pedestrians—with 18- to 30-foot metal bollards. The largely unfenced Texas border follows the Rio Grande River.

To accommodate small wildlife, printer paper-sized passages known colloquially as “cat doors” were built into the wall in some places. A recent study found that mountain lions, badgers, collared peccaries, and coyotes crossed the wall 16.7 times more frequently where the cat doors existed compared to sections without. Black bear, deer, and wild turkey could not squeeze through the passages, which suggests that jaguars and Mexican gray wolves would not fit either—although cameras did not observe these rare animals in the study.

Conservation scientists have developed bridges so wildlife can cross highways, which have proven hugely successful. Could an innovative design be developed that allows jaguars and other wildlife to pass through the border wall where it exists, or in areas it may be built? That remains to be seen.

A Bigger Table

They say ‘build a bigger table, not a higher wall’— but that’s not the direction Trump’s America has taken. The border wall’s impact on ecosystems and wildlife—and people and cultures—is without precedent in North America, or perhaps anywhere. Even the CATO Institute, a conservative think tank, argued in 2022, “It’s time to just admit: Trump’s wall did not work.”

The consequences of a border wall, whether complete or in portions, may take time to reveal themselves, but no doubt this continent-wide ecological experiment will harm gene flow, populations, and species, not to mention human lives and our country’s relationships with our historical allies.

“The original mistake is imagining that human beings are separate from the environment; human beings are a part of nature,” says Basaldú, who has fought the border wall in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley. He notes that Central American, Mesoamerican, and South American people have migrated and moved back and forth freely throughout these regions for many thousands of years prior to European colonization.

“Whatever species that was used to moving across this land prior to the invention of the wall … has an inherent right to continue to do so,” adds Basaldú, whether humans, jaguars, or any creature. “The wall simply interrupts that. And that is that interruption is violent. That interruption is destructive.”

A wall built across the entirety of the southern U.S. border from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean will truly sever connectivity for wildlife at a continental scale. Even if it’s just completed across the Arizona border, jaguars may never cross freely again. But people, innovative creatures that we are, will continue digging sophisticated tunnels underneath the wall, or climbing over, making the wall a fool’s errand with massive costs.

-30-

Due to an editing error, this sentence originally stated the contract was for $7M instead of $70M for seven miles of border wall. Deceleration regrets the error.