“This is outta hand,” fumed Jonathan Bunting of Nugreen Metals, an e-waste recycler appointed to the City’s new Auto Parts Recyclers and Metal Recycling Entities task force, as he gathered up his things to leave mid-meeting. “It’s the fourth meeting and we’re still going over the first section of code.”

Not long after, Andy Castillo, another appointee to the community side of the task force table, also stormed out.

It was a surprising punctuation to what on the surface billed itself as a highly technical affair—sifting through and revising two chapters of the City code regulating auto parts and metal recycling facilities. For years, fenceline neighbors in the South San, Quintana, and Thompson neighborhoods had been subjected to the fumes, fires, and explosions of daily operations at the many metal and auto parts recyclers that crowd San Antonio’s Frio City Road corridor. A Council Consideration Request filed by District 5 Councilwoman Teri Castillo in November 2023 had counted over 100 code violations across 75 facilities by June 2023. Monterrey Metal Recycling Solutions (until recently Monterrey Iron & Metal), a family-owned recycler in operation for over a century, had attracted particular community ire for the six structure fires that broke out at its 30-acre facility since 2021, affecting air quality in adjacent neighborhoods.

Now residents had been able to exert enough pressure to force the City of San Antonio to create a new task force dedicated to mitigating some of these public health impacts. There was just one thing: industry, community, and city had to sit down together and agree on revisions.

The challenge of this task became apparent from the very first order of business at the first substantive meeting—weeding out anyone with a legal beef with the City.

At the group’s second meeting on September 30, city staff asked all task force members to sign an affidavit (PDF) stating that neither they nor members of their family “have an active lawsuit or threat of lawsuit against the City of San Antonio.”

Community stakeholder Debbie Ponce was caught off guard by this requirement for membership, given her efforts to support the resident organizing that had led to the task force. She works “in the trenches,” the Public Citizen organizer said, assisting numerous grassroots organizations that routinely challenge City policy and priorities, such as those who have been advocating for Soap Factory and Robert E. Lee tenants facing displacement from elected interests in constructing a downtown baseball stadium.

If those groups were to sue the City on behalf of tenants, for example, “I’m affiliated,” Ponce said.

Eventually, City Attorney’s Office staff would clarify to community stakeholders that “affiliated” meant not being a supporter or member of a group involved in legally challenging the City, but rather “serv[ing] in a decision-making capacity, such as an officer/chair of an organization,” according to a definition Ponce received from the City’s Development Services Department and shared with Deceleration.

It now appears that the City’s requirement was less about concerns over fenceline communities stirring up trouble and more about recyclers suing one another and, for good measure, the City of San Antonio. One local metal recycler sued the City earlier this year, accusing it of unfair and arbitrary code enforcement practices, following an extended legal beef with a neighboring recycler.

A community meeting Deceleration livestreamed in February 2024 captures some of these tensions. Midway through the meeting, Daniel Hack, owner of Texas Auto Salvage, told Development Services Director Michael Shannon that he sued the City because its code enforcement officers had a history of “picking winners and losers.” He claimed at the meeting that City staff had been aggressively inspecting his operations, despite what he described as a lack of violations, while letting other recycling yards with multiple violations slide.

Beneath the highly technical scuffle over code enforcement and the legal affidavits required to discuss it, then, are lived and deeply felt histories of conflict—between neighbors and recyclers, but also between City regulators and recyclers, and at times even between recyclers themselves.

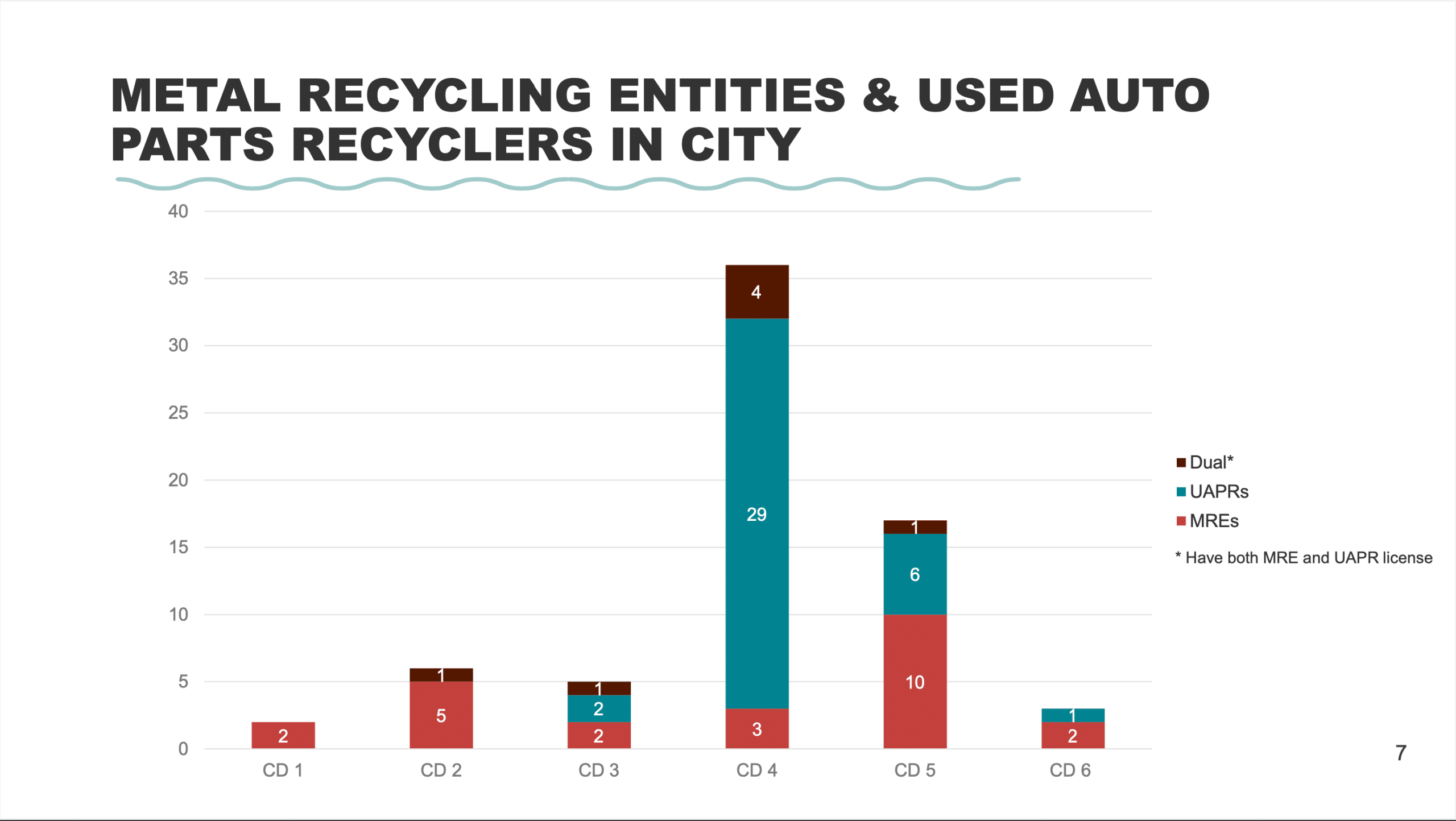

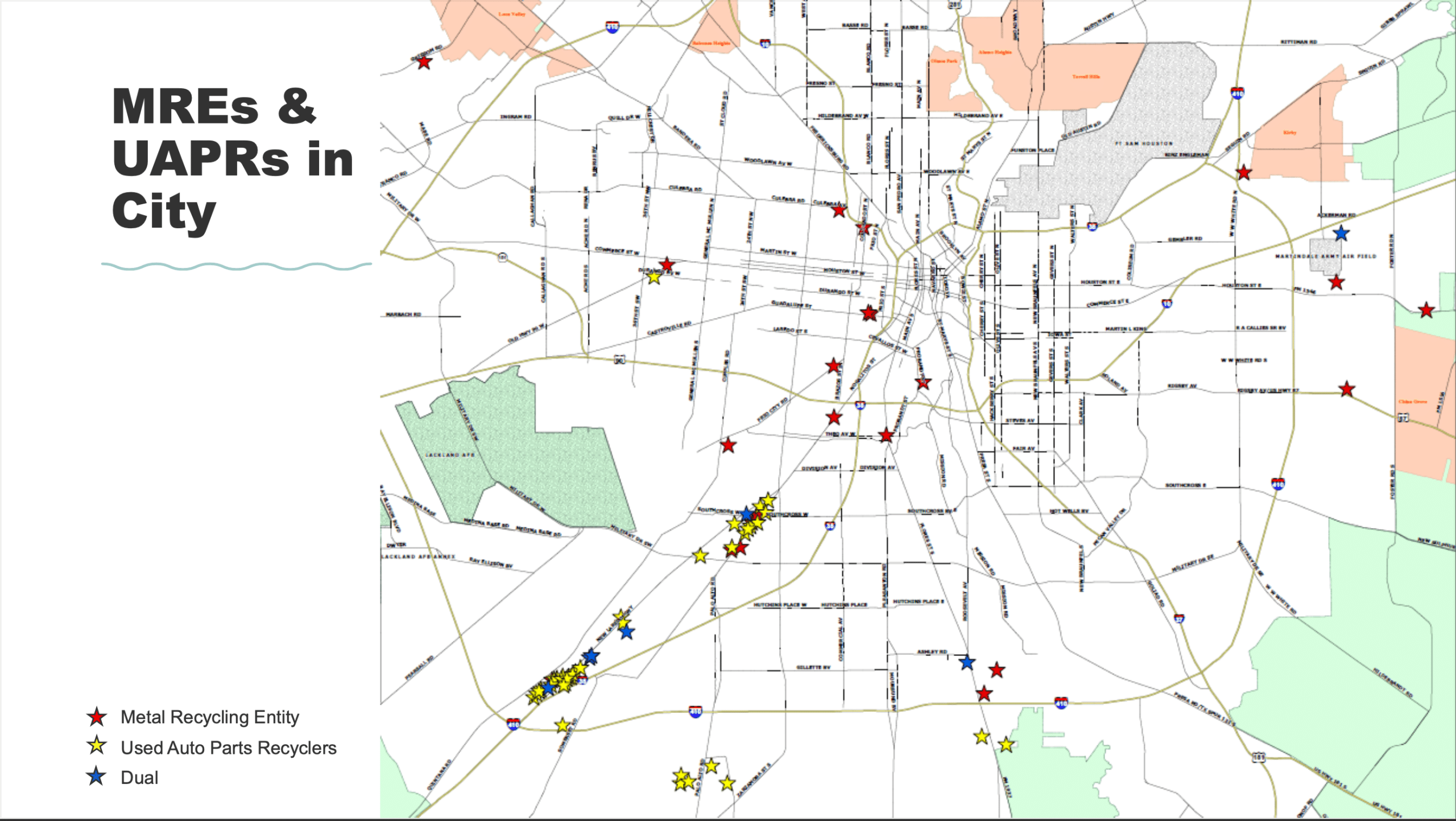

Scrap metal and auto recycling yards are a common sight for anyone who lives on the City’s South and Westsides, with the majority of these facilities concentrated in Districts 4 and 5. Neighbors in the Lonestar neighborhood just north of Highway 90, for instance, will remember Newell Recycling, a mainstay of EJ toxic tours in San Antonio in the 1990s and 2000s.

I never pass the former Newell—acquired by Commercial Metal Co in 2014—without thinking about something the late Brenda Davis, Eastside EJ organizer, mentioned once as we drove by. Waiting for the bus one day just outside the facility, she said, Newell had released a gaseous orange substance that on inhalation burned her nose hairs. It’s hearsay based on memory, but it captures something real about neighbors’ sense of alarm and uncertainty about the risks of living next door to industrial-scale recycling yards.

Robert Pérez also remembers Newell, having worked for 11 years at Lone Star Brewery next door before purchasing his first home—right across the highway from Monterrey, where he has lived for almost five years. At the time, he didn’t realize what this would mean for his family’s day-to-day quality of life, describing the noise of its 24/7 operations and the film of dust, “brown, flaky,” that coats his backyard, pool, and cars every day:

“When I bought the place,” he said, “[it] had a swimming pool in the backyard. I spent thousands of dollars getting that pool up to date with new equipment. I did all the plumbing because it had leaks. And every day I wake up to a big old film of dust on the top layer. And when the wind blows, all that dust, all [that] aluminum paper, is all over my yard.”

Even worse have been the fires, some of them “burning for days” and requiring his family not only to remain indoors but also “turn off [our] a/cs” in the middle of summer.

“It’s been like five fires since I’ve been there,” Pérez recalled, “and I’m not talking about [the] small ones. I’m not saying there’s a fire every week, but [even] last week there was a lot of smoke like three days in a row. And all that smoke goes to where we live.”

Although questions of climate justice in recent years have tended to eclipse classic EJ concerns over toxics and facility siting, the experiences of Pérez and his neighbors remind us that these more foundation EJ issues clearly persist.

The concept of environmental racism, in fact, is based on a 1980s finding that sixty percent of all hazardous facilities are sited in Black and Brown communities, according to a landmark report by the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice. Race, in other words, even more than class, is the biggest factor in where hazardous materials and industrial processes are located. These findings have been assessed (2007) and re-assessed (2021) over the decades, only to find not much has changed about who lives next to the most polluting facilities.

It has largely been these sort of fenceline struggles that led to the City’s task force. After the last fire at Monterrey in September 2023, neighbors who had complained for years about the public impacts of smoke, noise, and dust from local recyclers finally garnered needed attention.

At a November 2023 meeting, Texas State Senator José Menendez told attendees about more than 30 investigations into Monterrey by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, with at least one still open. Meanwhile, the City’s Development Services Department reported logging 18 citations for code violation, none of which had been resolved. For its part, Monterrey issued a statement to local TV news that the fires were outside its control, due not to code violations but to the combustible presence of lithium batteries in some of the scrap metal brought to them.

D5 Councilwoman Castillo’s response was to file a Council Consideration Request (CCR) calling for an “ad hoc task force of stakeholders including representatives of neighborhood residents, SAFD [San Antonio Fire Department] staff, DSD [Development Services Department] staff, industry representatives, and subject matter experts” to recommend updates to Chapter 11 (fire prevention) and Chapter 16 (licenses and business regulations) of city development code.

The City also took the facility to court in December 2023 for code violations and revoked Monterrey’s license in February 2024, giving the company 30 days to appeal before finally reaching an agreement that allowed them to continue operations on certain conditions. To avoid having to appeal this revocation before City Council, Monterrey agreed to weekly inspections for six months, a $10,000 fine, and compliance with all TCEQ regulations. If any violations were found during that six-month period, the revocation would continue with a three-day appeal process.

In our February town hall livestream, the City’s Development Services Department delivered these updates to Monterrey neighbors, who were incensed to hear Monterrey would remain open. As one elder put it, the facility had long been a source of “PTSD-DB—PTSD del barrio.” Two neighbors described tremors in their homes and cracks in their walls, which they attributed to periodic, and unpredictable, explosions.

“What are those explosions?” one of them asked, revealing the irony of living so close to something so impactful about which one knew so little. A Monterrey rep explained that while they tried to sift out things like propane tanks or batteries, those materials sometimes escaped detection and went through the machines undetected, leading to explosions.

While Monterrey successfully passed its six month period of inspections without further violations, neighbors like Pérez feel like this has made little difference in the everyday experience of living next to the company.

“The only thing I did see a difference is, I believe every other Sunday they’re—I don’t hear them working. You know, where it used to be 24/7. But like an impact [of the more frequent inspections]? No, not at all. I have not seen no kind of difference. Everything’s still dusty. I still see smoke there. I hear all that loud noise 24/7. So to me nothing has changed.”

Deceleration reached out to Monterrey with questions intended to help us better understand how daily operations have changed, but have yet to receive a response.

What Pérez and neighbors who spoke at the February community meeting suggest, then, is that the public health risks of living near metal and auto recyclers stem not just from code violations and arbitrary enforcement—but from the regulatory insufficiency of the code itself, last overhauled in 2012. As one neighbor said at the community meeting, referring to the City’s agreement with Monterrey, increasing the distance between piles of scrap or building a fence may mean “it look[s] pretty…but it ain’t fixed.”

Though approved in March 2024, the Used Auto Parts Recyclers and Metal Recycling Entities Task Force didn’t formally get to work until September. The makeup of the task force seeks balance, with eight industry reps and eight community reps refereed by an alphabet soup of departmental acronyms from the City (DSD, CAO, SAPD, SAFD, SAWS, SWD) and state agencies (TCEQ). Notably, though, three of the “community” seats are filled by what the CCR refers to as “subject experts,” meaning professors of public health, environmental health, and urban planning.

@robertperez8367 ♬ original sound – Robert Perez8367

TikTok video uploaded by Robert Pérez.

Another “community” seat is filled by a climate-minded e-waste recycler—not a metal or auto parts recycler, true, but arguably closer to industry than neighborhood perspectives. What remained, then, was a visual lopsidedness to the table at the October 28 task force meeting: four neighborhood folks gathered on one end, a chair conspicuously in between, then eight industry stakeholders and two university folks clustered together on the other end.

Four meetings in, the visual tensions between these two sets of interests is clear at the most basic level: defining hazardous materials. Industry stakeholders at the October 28 meeting strenuously objected to an expanded and far more explicit definition requested by community stakeholders, which, based on details from the international fire code, would add and provide examples for ten substances posing physical or health hazards—including the explosives and blasting agents brought up by so many neighbors in public commentary.

Throughout the meeting, industry reps, in particular Monterrey CEO Jordan Vexler, questioned the purpose of listing these hazardous materials explicitly. “How will this list be used?” she asked repeatedly. “What is the intent?” When Development Services Department staff asked what her concerns were in defining this in city code, Vexler first protested that the details were redundant: “If these details come from the fire code, there’s no need to include them here. Just reference the fire code.”

Melissa Ramirez, Interim Deputy Director of the City’s Development Services Department, then responded: “This expanded definition is meant to clarify things for the citizen, not the inspector primarily. That part [inspections/enforcement] has not been discussed. It’s not just for the officers or the industry, it’s for citizens.”

Eventually industry reps named their fears around making hazardous materials more visible in city code. If the public more easily knew the materials they worked with as a matter of course, “someone may see some of these materials come through our site and think they’re in jeopardy,” said one recycling industry representative.

Ponce tried to speak to this fear, reassuring the recyclers in the group that “this group of recyclers [on the task force] are among the best operated in our city. But this list will affect all recyclers, including those that are less good, which is what will protect the community. I feel strongly we cannot remove this language.”

“I disagree,” another recycler immediately responded, “we need to remove it.”

Ultimately the question of how to define hazardous materials was tabled, but not before Bunting and Castillo left the room in frustration.

It was clear that recyclers were fearful that if communities have too much information about what metal or auto parts they are working with, residents will be quicker to use code enforcement against them. From the community side, there are fears that the City—which until now, they insist, has turned a blind eye to the worst local polluters—now seeks to make a visible example of some companies to look like it’s doing something, while skirting a deeper accountability.

Though on its surface a technical matter, recycling code reform reveals a chasm of complicated emotions and political dynamics between regulators, industry, and community. It also suggests, as Ponce does, that histories of environmental racism are as much about the failures of the local regulatory apparatus—witness the court case between the two recyclers, each one accusing the other of currying favor with the foxes guarding the henhouse—as they are about industry practice.

In some ways, these real time struggles between industry, regulators, and the communities caught in between bear out a point documented by David Pellow in Garbage Wars: The Struggle for Environmental Justice in Chicago, a classic work of EJ sociology.

On the one hand, Pellow writes, recycling is an environmentalist ethic drilled into us from the time we’re tiny, which cultivates a certain kind of self—one that expresses cares for people and planet by thinking about the destinations and impact of materials throughout their life cycle—as much as it shapes a set of urban practices. But there’s recycling as rhetoric and then there’s recycling as industrial reality, which often turns out to be as hazardous an industry for its workers and neighbors as other manufacturing processes whose toxic impacts we more readily recognize.

For the irony here is that recycling facilities are in fact “key to our city’s recycling ecosystem and circular economy,” as stated in Castillo’s CCR.

As Christina Ramirez of Pam Recycling pointed out, their client base is the community, who rely on these facilities to keep discarded materials from “ending up in the street” and out of landfills. As such, frontline struggles over Southside recycling facilities raise critical questions about the ways in which we are always connected to and implicated in the waste streams we seek to regulate. In an industry premised on our own deep implication in economies of extraction, disposability, and toxicity, what is real accountability?

And yet frontline neighbors like Pérez, who worked next door to the former Newell Recycling for eleven years before moving next door to Monterrey, believe accountability is possible.

“Newell Salvage has come a long way,” he said. “From what I have seen, they have cleaned up their act.”