In the summer of 2007, a pump at the Blue Line Corporation in East San Antonio was “inadvertently turned off,” releasing about 50 pounds of hydrochloric acid into the air. Five employees at a nearby business began to experience breathing difficulties and called emergency responders. Four were examined onsite for complaints of upper respiratory trouble and one was hospitalized, according to TCEQ records.

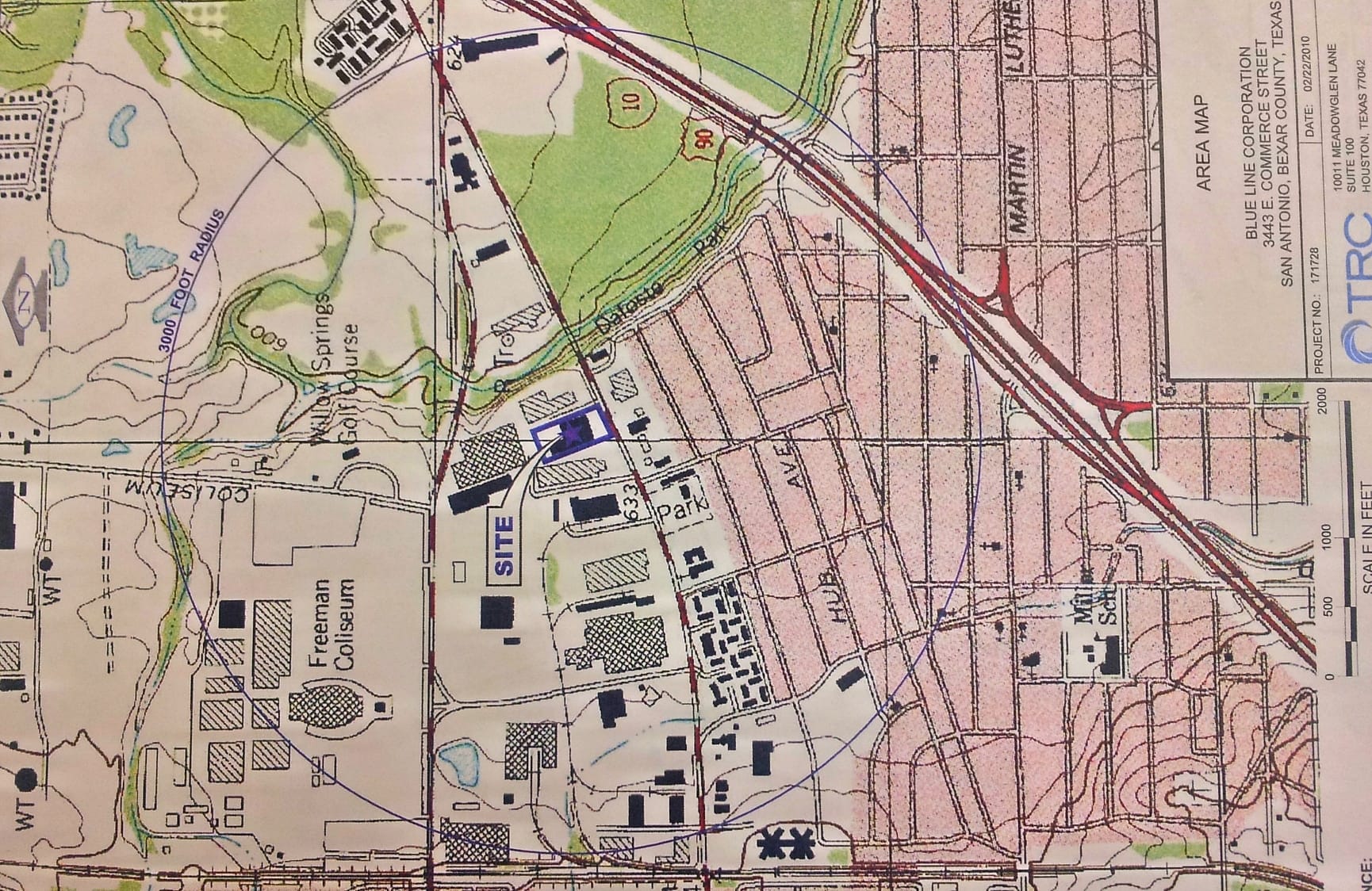

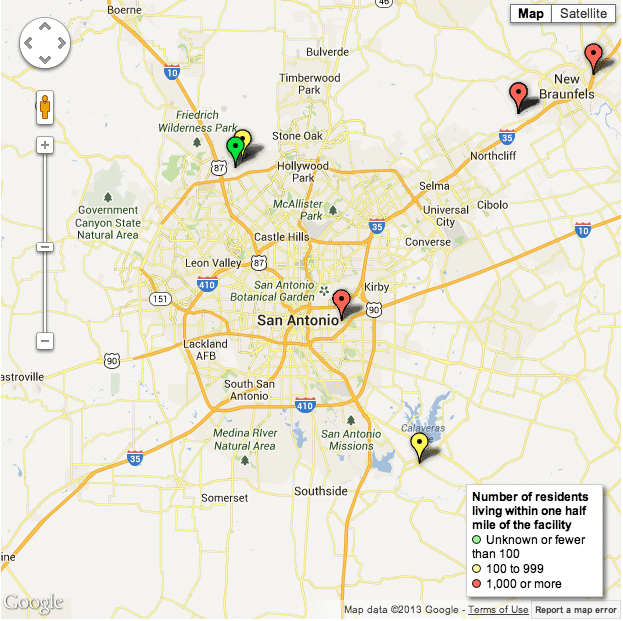

Blue Line, located a few blocks southeast of the AT&T Center (3443 East Commerce, see red flag at center of the map below), was cited for two violations and fined $3,500.

Then the company, which also handles large volumes of ammonium nitrate — the same chemical responsible for the explosion of the West Fertilizer plant that killed at least* 15 earlier this year — applied for an expanded air permit.

TCEQ’s director of the air permits division wrote Blue Line President Jon Blumenthal on May 26, 2009, to say that a five-year review of company practices revealed the company’s compliance history was “poor.” There were two other spills on the books at TCEQ from 2007, one of which involved a spill of 680 gallons of hydrochloric acid.

While the permit was granted in 2009, the company’s compliance history required “special conditions” he added, things like regular sampling of the four s

crubbers that limit the amount of pollution coming out of the plant’s stacks and annual inspection of the tanker trucks. And Blue Line would have to apply for license renewal in five years.The TCEQ’s air director also warned Blumenthal about the importance of compliance, saying that future problems could get in the way of future permit approvals.

However, a string of odor complaints that poured in even as that permit was being reviewed apparently didn’t cause a ripple in the process thanks to follow-up investigations that lagged weeks — and, in one case, nearly a month — behind the dates the complaints were first fielded.

A complaint of a “chlorine-type odor” on June 30, 2008, wasn’t investigated until July 16, according to records on file at the TCEQ’s San Antonio office. Another similar complaint made December 18, 2008, wasn’t followed up on until January 12, 2009. A third odor complaint on February 4, 2009, wasn’t investigated until February 13, 2009.

In all cases, the investigator reported they “did not confirm the complaint.”

A compliance review performed by TCEQ in 2010 found that “the previous poor rating has been improved significantly,” and the company was reclassified as “satisfactory.”

And air pollution issues have not resolved.

Employees at neighboring Walton Signage were overwhelmed by a “chlorine odor” on October 15, 2012. Employees reported to the TCEQ investigator (when the investigator showed up four days later) that they heard an alarm go off at the complex next door and hurried to close their building and turn on the exhaust fans.

While no one had to be hospitalized, the TCEQ’s investigator’s report said they ranked the power of the chemical odor at a nine on a 10-point scale.

Blumenthal told the investigator a pump in one of the scrubbers had failed — as did the back-up pump after that. Later, after the company “immediately shut everything down,” they discovered a problem with the wiring.

The failure released a company-estimated 10 pounds of hydrochloric acid and 5 pounds of chlorine into the air.

Blue Line is far from alone in handling ammonium nitrate in the San Antonio area. It’s just the most centrally located.

The newest air permit on file allows Blue Line to handle as much as 500,000 pounds of ammonium nitrate over any 12-month period.

Blue Line’s Blumenthal was not immediately available for comment.

—

* Recent reporting from the Dallas Morning News and elsewhere suggests the death toll from the explosion is not complete.