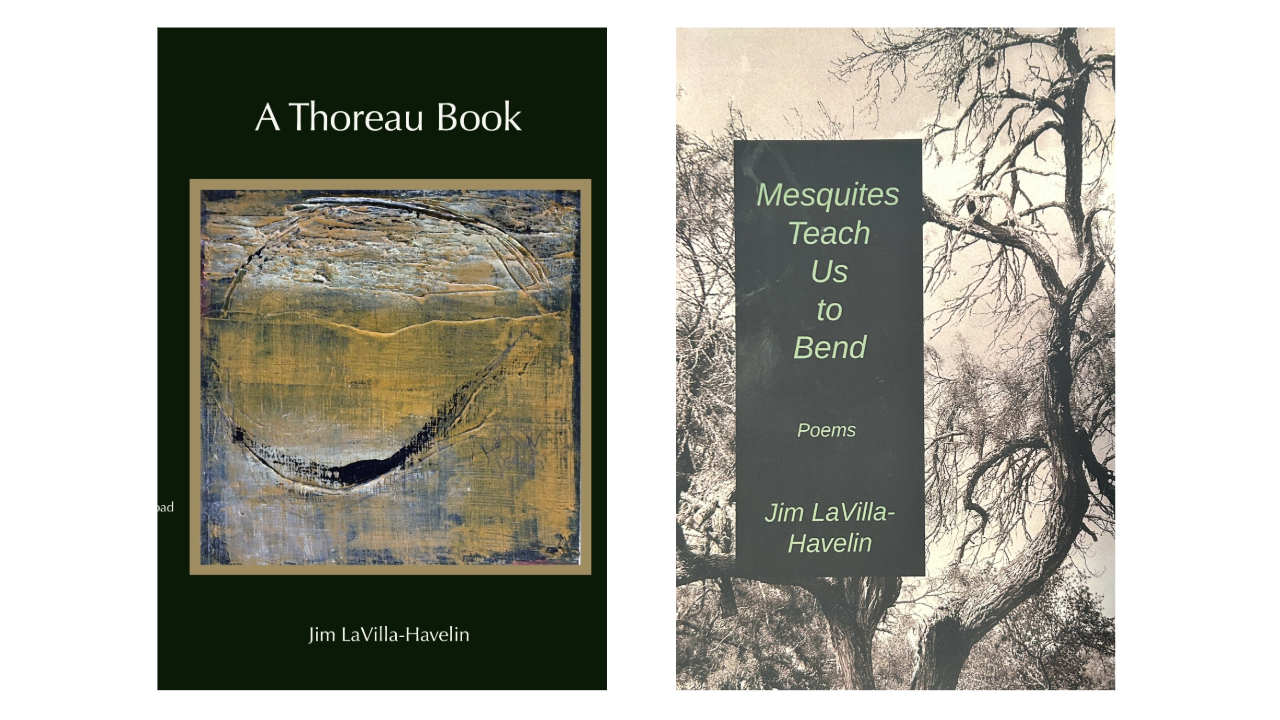

Mesquites Teach Us to Bend / by Jim LaVilla-Havelin / Lamar University Literary Press, 2025

A Thoreau Book / by Jim LaVilla-Havelin / Alabrava Press, 2025

In 2025, poet Jim LaVilla-Havelin—co-founder of Words for Birds and longtime organizer of San Antonio’s National Poetry Month calendar of activities— published not one but two new poetry collections of deep interest to Deceleration readers: Mesquites Teach Us to Bend, a full-length collection, and the chapbook A Thoreau Book. (He also co-edited a third book, the latest volume in the University of Houston’s “Unsung Masters” series focused on the late Rosemary Catacalos, who in 2013 became Texas’s first Latina poet laureate.)

As such, the task of reviewing such a prolific and gifted poet’s newest collections requires a certain amount of audacity. But when one is called to review two new collections of poetry—well, only fools rush in where angels fear to tread. And yet...

Poets have a particular obligation to see, to listen, to observe intensely. Their words like antennae, they gather and collate information about the world around us: its tastes and its temptations, its dangers, its delights. In Mesquites, LaVilla-Havelin not only takes this duty seriously, he accomplishes the work with skill and grace.

There is a sparseness running throughout this collection, a quietude demanding that we set aside our addiction to that which is new and shiny and technologically advanced in favor of that which is raw and real and perhaps hopeful. LaVilla-Havelin doesn’t focus his attention on the massive power of a raging sea, or postcard-ready scenery of a mountain range. Rather, he calls us to examine the simple beauty of the weathered, scruffy landscape in Atascosa County (southwest of San Antonio, Texas).

For LaVilla-Havelin, originally from upstate New York, for the past 21 years has made his home on a land which is always pushing back against the constant foreboding peril of drought. Reading this collection, I’m reminded of something Robinson Jeffers said about our need to focus on “the astonishing beauty of things.”

The collection is divided into four sections, offering us a diary of the change of seasons, punctuated by interludes and postludes. These sections are interspersed with exquisite black-and-white images by local photographer Ramin Samandari. The scenery runs throughout the collection, and one begins to suspect the landscape, and its denizens, reflect something about the character of the poet.

For example, in the collection’s title poem “Mesquites,” LaVilla-Havelin notes that the trees have become twisted and describes how the birds “fly from them, nest in them / come back to them / and all their / turning / as I do.”

In his poetic observations of Atascosa County, LaVilla-Havelin counts among his neighbors the rabbits, the barn owl, the hummingbirds, the caracara falcons, the agave plants, the cows and horses and, of course, the mesquites.

Although this place is certainly home to the poet, one shouldn’t imagine a placid countryside. In fact, at times the landscape seems almost Shakespearean. He imagines a mesquite which may have been caught in a windstorm or struck by lightning: “leaning, bobbing in the storm / a Macbeth or Lear scene.”

Jim LaVilla-Havelin reading from new works. Images: Greg Harman

Listen to LaVilla-Havelin read (and be read) at this recent "Three Books, One Launch" event with fellow writers James Finley & Marisol Cortez. Deceleration Video.

These poems urge upon us the deep and rich connection between all things. This entails a commitment to non-violence, as evidenced in the poem “I Name the Spider.” The poet says, “I name / the spider / so someone else, hearing me address it, / does not just knock it down and step / on it.” The spider has a name and a place in the history of this landscape: “Charlotte is the star of many photos / of our place.”

Something in these poems invites us back into the dawn of creation, back to a world which is always both new and in recovery.

While one might take up residence in this landscape, it takes the wisdom of someone like LaVilla-Havelin to recognize that the land is also staking a claim upon us. We are invited to examine the primordial relationship between us, the land, and the creatures which share it. In “Juncture,” LaVilla-Havelin reminds us, “this is where / the world begins.”

LaVilla-Havelin cautions us of the need for care and attentiveness to the natural world around us. We hear echoes of the great poet Matsuo Bashō here, who said, “No matter where your interest lies, you will not be able to accomplish anything unless you bring your deepest devotion to it.” In the context of several meditative techniques, this is called “mindfulness.” But I think I prefer the wisdom of Ferris Bueller, who reminded us: “Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”

In A Thoreau Book, Jim offers us the gift of his reflections on a pandemic project—reading the fourteen volumes of the journals of Henry David Thoreau. In “Re-Visions. Living Through Change,” he asks a crucially important question, one that in many ways underpins both of these collections:

what more could we do now

if we wanted to live

deliberately?

It’s exactly the kind of question Bashō would invite us to ponder. Our “deepest devotion” to the world around us compels a particularly poetic attentiveness.

The choice of Thoreau as a companion through the pandemic is a fascinating one. In many ways, Thoreau was a polymath—a poet, essayist, philosopher, naturalist, transcendentalist, abolitionist, and proto-environmentalist. He also pretty much invented the concept John Lewis would later call “good trouble” in his essay “Civil Disobedience.” So in many ways, Thoreau is the perfect companion for several pandemic-driven months of isolation, as well as the days of conscience-testing political turmoil in which we currently find ourselves.

Despite the heaviness of the world events which inspired his Thoreau project, throughout this collection one also finds LaVilla-Havelin’s delight in playing with words and the sound of words. Within his work, one can also hear the echoes of William Carlos Williams. He’s not hiding it; in fact, he playfully acknowledges this debt in “Works”:

Doc Williams knew the uses of the

wheelbarrow

beyond the

simple

image.

Clearly, the author has used Thoreau as a teacher, studying his method of observing the world. And so, “on the rare days / he doesn’t read / Thoreau’s journals / he notices /that he doesn’t / notice / things.”

Within these two collections I hear echoes of Vonnegut’s famous answer when he was asked about the purpose of life: “To be the eyes and ears and conscience of the creator of the universe….” These collections invite us to do just that, to take stock of the world around us.

Or, as Mary Oliver observed,

To pay attention

this is our endless and proper work.

Especially in hard times, Jim LaVilla-Havelin calls us to begin that endless and proper work, alert to the world around us, with strong, resilient hearts that care deeply for the world around us.