Leer esta página en: Español

Winter Storm Uri was not one-and-done. Deceleration’s Winter Storm Survey suggests that the days-long freezing blackout is a lingering specter haunting our collective psyche. Only community-led solutions-making can exorcise it.

Greg Harman & Marisol Cortez

The city’s 311 line was open and accumulating complaints and concern as crushing Arctic air flooded over the Great Plains and into Texas, freezing up gas wellheads and wind turbines across the state. Others followed in the months after the February 2021 storm left 300,000 residents in the freezing dark—many for several days in a row—after the state power grid operators called for energy reductions at City-owned CPS Energy. The state’s power grid, we learned soon, was less than five minutes away from a catastrophic collapse that could have left millions without power for weeks or months.

Questions were plenty, including how our own utility’s coal and nuclear units failed to power up at such a critical time.

Wrote one resident, as compiled and republished post-blackout by a new committee tasked with understanding the many state, city, and utility storm-related failures:

“Why is it I was without power and water for 4 days? Why is it that our family members (many handicapped and elderly), that we are care givers for had to do the same and we were unable to render them aide due to impassible roads for 3 of those days. Why is it I will never trust city, state or federal government and utility companies again?

And another:

“Why did so many things go wrong? Did we not learn from the past or did you ignore previous warnings about our electrical grid?”

Then there were the angry directives, such as:

“Get some ********* snow plows”

Though informal, Deceleration’s own community survey also recorded the frustrations of residents struggling to care for elderly family members and young children. But far less mentioned in public discussions post-Uri has been the lingering physical and emotional damage many respondents cited in our survey. Such results are a reminder that the storm is not just a body count but a lingering force that continues to damage our collective well being. In reviewing our elected leadership’s response, we continue to advocate for a better way forward: A pathway not only to navigating grief and trauma but to the community-led creation of a cleaner energy and justice-based economy.

In the days after the blackouts, Mayor Ron Nirenberg would assemble the Community Emergency Preparedness Committee that gathered the public comments above. That team enjoyed extensive weekly conversations about the nature of the storm and fumbled storm response, ultimately releasing a report that criticized issues upstream (the state’s failure to tie into the rest of the US power grid) and those directly in our control (failing CPS Energy coal and nuclear plants). They also praised community mutual aid efforts left struggling to compensate for the many gaps left by the botched governmental response to the outages.

However admiring of community-led disaster response, the team, made up mostly of current and former City Council members, declined to seek much community involvement in the committee process. It took months, for example, for them to manage basic live broadcasting functionality or reliably populate their COSA webpage with meeting videos so folks could follow along or contribute meaningfully. Their survey page explicitly seeking community input (“We recognize that our residents were also impacted…”) was little more than a comment box with blank fields added to collect demographic information.

As Deceleration wrote at the time, even professional surveyors failed to ask fundamental questions of local residents that would betray actual concern. Deaths—246 confirmed by the state with 16 in Bexar County, but likely more than 750 statewide—were calculated and dutifully reported in the media. But these efforts failed to tabulate the cumulative weight of the storm in terms of illness, disability, economic hardship, and psychological damage, to say nothing of the storm’s impact amid the ongoing stress of COVID-19 isolation, illness and sustained economic struggle.

Asking questions is more than just an exercise. It’s more than a demonstration of basic respect for community. As a growing body of research into disaster recovery shows, it’s also the starting point for real recovery.

As we shared last year:

Writing on community tragedy, grief, and healing in the Journal of Community Practice, social workers Nancy Kropf and Barbara Jones have emphasized that public trauma from climate disasters to mass shootings require public meaning-making processes to restore community functioning. ¶ To date, the most moving expression of shared trauma-processing occurred after nearly 110 residents signed up to speak at the CPS Energy Board of Trustees meeting on February 22, 2021, held days after power had been restored to most of the city. The expressions of grief, confusion, and rage delayed the start of official meeting business by nearly three hours. ¶ This was an opportunity to invite residents into a deeper level of solution-seeking. Yet CPS’s own board minutes distilled these critical hours into a mere thumbnail.

With the outage located at the nexus of our climate crisis and energy policy, the winter storm response had to also be a climate response, but San Antonio’s city leaders actually sidelined the climate conversation even as they sought to hold CPS Energy more accountable by emphasizing energy security, reliability, and affordability. Energy conversations abounded in 2021 within the Community Emergency Preparedness Committee, followed by the Municipal Utilities Committee. On the utility’s side of the street, the formation of CPS Energy’s Rates Advisory Committee actually saw a deterioration in conversations about climate response, such as the benefit of energy efficiency and free home weatherization programs.

“Nobody is framing this around climate or the emissions,” San Antonio’s Chief Sustainability Officer Doug Melnick told Deceleration late last year of the RAC. “I think we need to re-center back in why this discussion is so important. It’s not just about rates. It’s not just about reliability. It’s about if we don’t address this [then] these are the ramifications. And I feel like it’s gotten lost.”

Josef Ruzek, a research professor at the Department of Psychology at the University of Colorado, specializes in the prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder. He wrote recently in Psychiatric Times that “involvement in activities intended to reduce global warming and address proximal climate problems is likely to bring direct psychological benefits, in addition to creating a safer and sustainable local environment.”

Yet our leadership has struggled to advance two intimately-bound realities: first, that extreme weather is increasing, and is increasingly driven by human-caused planetary warming. And, second, we need to both reduce activities causing the overheating of earth’s systems and strengthen our collective responses to better protect one another.

Though a non-scientific survey with the majority of respondents almost certainly coming from Deceleration’s readership (meaning they are, among other things, more familiar with the science of climate change and need for action), we nonetheless hope this survey can make a small contribution toward reorienting our community to better prepare for future weather-related disasters. Note too that while these results are drawn from a limited survey size, this should not impact the significance of findings related to personal physical or emotional harm, given that our readership is not geographically isolated but spread across the city and the circuits of its electrical grid. If anything, this limited sampling begs a question that underscores the need for more systematic and randomized investigation:

How many others experienced lasting impacts from the storm that have gone unreported and unaddressed, simply for want of someone asking the right questions?

San Antonio Winter Storm Blackout Survey

Key Findings

1. In addition to the deaths, physical storm-related injuries were reported by more than one out of five surveyed.

Nine of 41 respondents (22%) said that their health, or the health of someone in their household, was negatively impacted by the storm-related utility outages.

While this is generally understood, survey responses provide more qualitative detail on the nature of these health impacts. For example:

“My mom, who lives with us and is undergoing treatment for metastatic bladder cancer, went without physical/occupational/immuno therapy for about 10 days.”

As other respondents detailed:

- “[I] came close to dying from the cold.”

- “My father and youngest son developed colds that lasted a week.”

- “I had an 11 month old baby who couldn’t sleep with blankets for safety reasons who I had to try to put to sleep in freezing temperatures with no heat and monitor throughout the night.”

- “PTSD, hunger”

- “Threatened partner’s ability to live b/c he relies on ventilators to breathe, so I kept 2 small tanks filled (about 2 hours each of life) and kept two larger tanks filled (8 hours each of life).”

Of those 9 respondents who reported outage-related health impacts in their household, two described needing to seek medical attention for loved ones with chronic illnesses who rely on electricity-dependent medical equipment:

- “[My partner’s] COPD became worsened. So, he needed to see doctor more frequently, which he was able b/c he has had his VA straightened out. But, leads me to think how much more people do not have this assistance?”

- “My cousin missed dialysis due to outages in San Antonio.”

Strikingly for such a small sample size, four respondents reported that someone they knew died due to the outages:

- “I am aware of one elderly resident of the Fair Avenue Apartment complex who contracted Legionnaire’s Disease in the weeks following disruptions to electrical/water service.” That resident then died about a month later. “Because no second case surfaced within a 12 mo window, Metro Health and SAHA [did] not have to treat it as an outbreak with a full investigation, and thus it has not been linked to the events of Winter Storm Uri. But to the family it seems likely that the source of the infection was water outages linked to the winter storm blackouts.”

- “My cousin died after missing dialysis during the freeze in San Antonio.”

- “Homeless people who died because the city refuse[d] to set up a city run shelter or more warming centers that would be run by the City and not Haven for Hope. People died on the snow.”

- “Not personally, but a neighbor [died.]”

2. The power outages were a blow to the community’s mental health.

We are unaware of any previous efforts to understand the impact of the storm-related outages on San Antonio’s mental health. Deaths and physical injuries dominate reporting, but more widespread and enduring may be the toll of the storm failures on our collective sense of well being. Seventeen of 41 respondents (41.5%) said their emotional or mental health was negatively impacted by the storm-related utility outages (choosing “more-than-moderately impacted” or “severely impacted” on a 5-point Likert scale). To our knowledge, this question has not been previously asked of San Antonio residents. Almost a quarter of respondents (10/41 or 24.4%) described their mental/emotional health as “strongly impacted.”

At the time they took the survey (which was open from April 2021 to January 2022), over half of those who responded to the question (17/31 or 54.8%) said that they had some level of unmet need related to the storm’s negative impacts on physical or emotional health. Seven (22.6%) reported that none or almost none of those needs had been met (choosing 1 or 2 on a 5-point Likert scale).

Notably, while roughly half of those surveyed participated in the months immediately after the freeze, 3 of 8 survey responses logged in January 2022 indicated unmet need.

In other words: We have not recovered yet.

3. Respondents blamed the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), the state’s Public Utility Commission, and Governor Greg Abbott, with energy deregulation coming in a close fourth.

While previous surveys have allowed limited options for assessing responsibility, we wanted to give respondents a fuller range of choices. Respondents placed ERCOT, the PUC, Abbott, and deregulation high on their list of culprits.

Two respondents wrote in Act of God or Mother Nature, and another two blamed CPS more generally, explaining:

- “CPS is responsible for giving us non-useful energy in 5-minute to 30-second spurts”

- “CPS needs to prepare better and charge large industry rather than small residential customers”

Another wrote in Mayor/City Council, clarifying further that the City could have blunted the impact of the storm by opening up the Convention Center much earlier than Councilman Roberto Treviño requested.

Other write-in options included mentions of the Texas Railroad Commission, regulator of the oil and gas industry in the state, and the Republican Party.

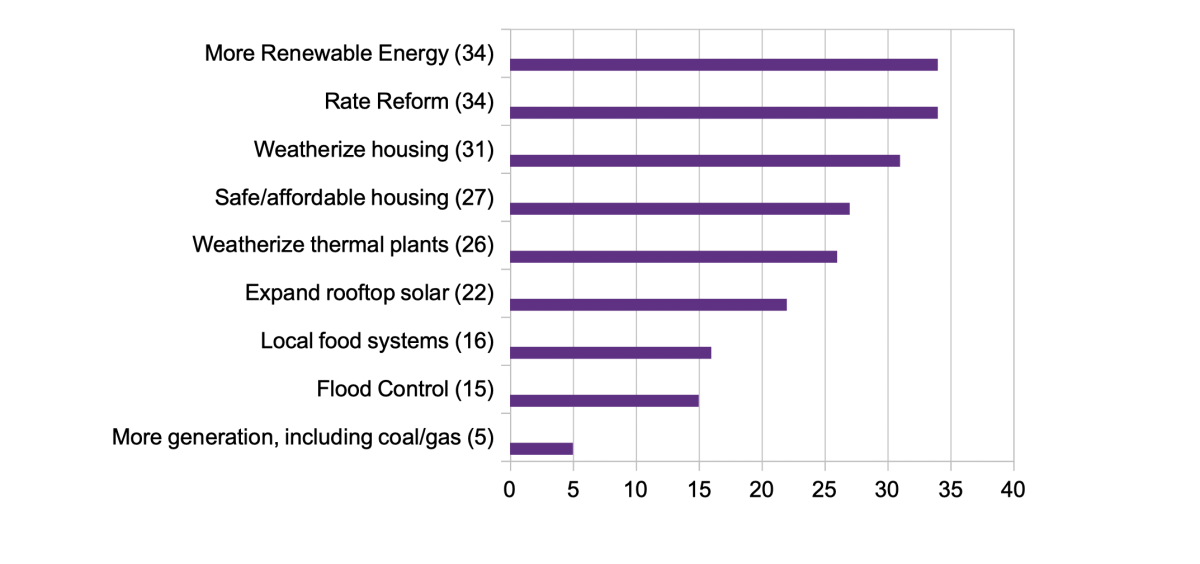

4. To prevent future extreme weather events from having similar impacts, respondents want to see more investment in renewable energy; utility rate reform placing a bigger share of costs on the highest users; weatherization of homes, especially in historically neglected neighborhoods; and investment in more safe and affordable housing.

Although the role of housing justice gets little attention in local and state conversations about the storm’s violence, it figured prominently in our survey, with both weatherization programs targeting, especially, low-income areas and access to safe and affordable housing scoring high.

5. Overall takeaways: Residing trauma, a deep desire for systemic solutions, and the need for more research asking the right questions.

A year after Winter Storm Uri, the primary takeaway from our informal community survey is that the Texas Freeze has had lasting, traumatic physical and emotional impacts. What also stands out is the systemic, upstream nature of the policy solutions articulated here as preventative measures, compared to the narrow, technocratic solutions that have dominated public discussions at the local and state levels.

And though our sampling pulls largely from a self-selecting readership already engaged on issues of climate and environmental justice, the responses collected here are nonetheless important in pointing out the kinds of questions decision-makers and media commentators are largely not asking community members. Think of these results, then, as what’s known within the field of quantitative research as a kind of concept testing study—a survey whose value lies in revealing what ground-level concerns and categories are bubbling up to inform more systematic future data collection efforts.

-30-

Like What You’re Seeing? Become a patron for as little as $1 per month. Sign up for our newsletter (for nothing!). Subscribe to our podcast at iTunes or Sticher. Share this story with others.