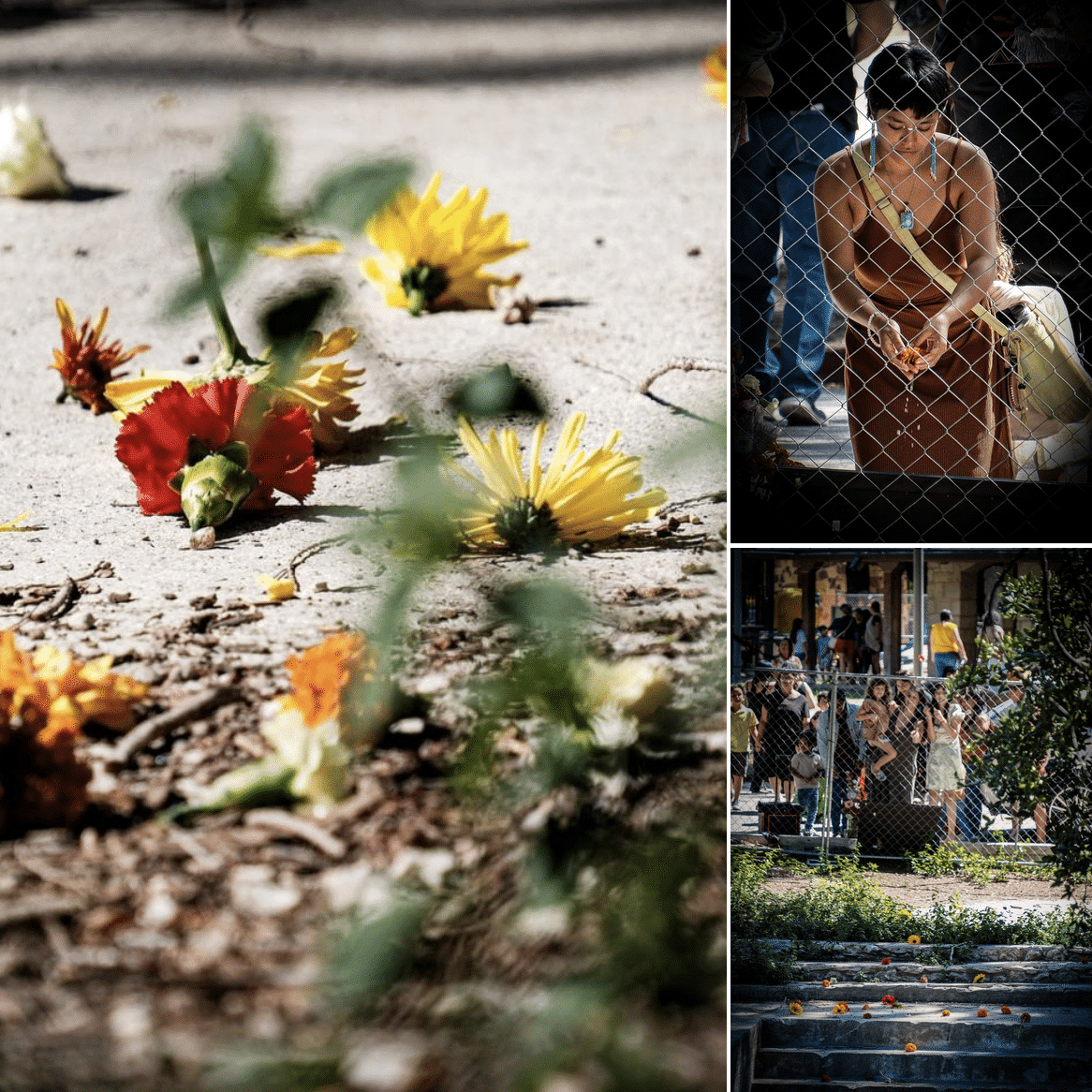

Small groups of 20 or fewer will be allowed to hold limited ceremonies beside the San Antonio River, but U.S. District Judge Biery rejects requests by members of the Lipan-Apache Native American Church to protect the trees and birds.

Greg Harman

“When asked by an anthropologist what the Indians called America before the white men came, an Indian said simply, ‘Ours.’”

“You can please some of the people some of the time, all of the people some of the time, some of the people all of the time, but you can never please all of the people all of the time.”

With these two quotes, U.S. District Judge Fred Biery suggests with a whimsical flourish that he is striking a middle ground in the case of Gary Perez & Matilde Torres vs the City of San Antonio. In actuality, the plaintiffs, members of the Lipan-Apache “Hoosh Chetzel” Native American Church, were granted a bare minimum of their request for access to a sacred site in the San Antonio River’s headwaters and protection of nearby birds and trees as a “sacred ecology.”

In short, Biery ruled that small groups of 20 or fewer members of the Lipan-Apache Native American Church will be allowed to practice their religious ceremonies at a sacred site beside the San Antonio River—for no more than an hour and only on “specified astronomical dates.”

The space sits on the river bank south of a one-time Whites-only swimming hole now on the cusp of being restored as part of a City of San Antonio redevelopment project.

Biery rejected the plaintiff’s request for the City of San Antonio to reduce the violence being directed at migratory birds in the upper reaches of the park as part of migratory bird deterrence efforts. And he ruled against taking any action on calls to seek alternatives to a planned mass tree removal that would slow the City’s project. Together, the presence of the trees and birds—cormorants, specifically—represent the “spiritual ecology” that gives life to Perez and Torres’s faith, the couple argued in court recently.

RELATED: “The Sacred & The Law: Indigenous Claims on Trial in Brackenridge Lawsuit“

“The Court finds the bird deterrent operation is in the realm of public health and safety,” Biery writes.

“To grant Plaintiffs’ relief regarding Item 3 would effectively put the Project on hold ad infinitum, given the different species’ migration patterns and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. There could not be an eight month window of opportunity to accomplish the Project.

When contacted by Deceleration, Gary Perez said that the couple plans to appeal their case to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

“We’re still being told where to go pray. This isn’t a concession at all. They want to schedule our time,” Perez said.

Biery seeks in his order to support what he describes as a “secular/religious symbiotic relationship” between the City of San Antonio and the Lipan-Apache Native American Church by crediting the City’s injection of recycled wastewater for keeping the San Antonio River flowing through the park.

“It is not particularly holy water nor the purity of the spring water Plaintiffs would like, but better than a dry riverbed,” he writes.

His analysis, of course, sidesteps the fact that the Blue Hole and associated springs around the headwaters of what many Native peoples know as Yanaguana would not be dry today but for centuries of colonial occupation of these once-Native lands and the massive amount of water use the City draws daily from the underground Edwards Aquifer that have all but eliminated spring flow most of the year.

Biery’s ruling does not grant full religious rights even during the limited times and numbers he allows for, however. He writes that he is seeking additional information before ruling if nighttime peyote rituals will be allowed.

He ruled additionally that no access for individual reflection or prayer would be allowed at the sacred site during the length of the City’s construction project.

“The Court notes that both Plaintiffs also practice Roman Catholicism whose places of worship provide numerous locations for individual meditation and worship. Moreover, Plaintiffs and the general public still have access to over 300 acres of Brackenridge Park for meditation in nature.

Perez acknowledge that the specific request was not made in the lawsuit to have unfettered access to the site. “But telling us we can go somewhere else because we’re Catholic is like, I don’t think the judge gets it, man.”

Read the judgement here:

-30-

Like What You’re Seeing? Become a patron for as little as $1 per month. Explore ways to support our mission. Sign up for our newsletter (for nothing!). Subscribe to our podcast at iTunes. Share this story with others.