Federal regulators are targeting Spanish-speaking workers early this year in hopes of reducing deaths during 2024’s extreme heat. But large gaps in Texas heat surveillance means another season of largely avoidable suffering and death looms for workers, migrants, elderly, unhoused, and incarcerated.

Greg Harman

Last June, Eloy Maldonado Valdez, 59, was passing cinder blocks to a coworker at a Rockport, Texas, job site. It was shaping up to be a grueling summer for outdoor workers—the hottest ever for residents in many parts of the state. It was in the mid-90’s when Maldonado began to feel sick. High humidity pushed the heat index closer to 110F, considered well into the danger zone for human health.

He laid down in the shade for a moment to recover. But he was soon found unresponsive and died, according to a federal investigation summary.

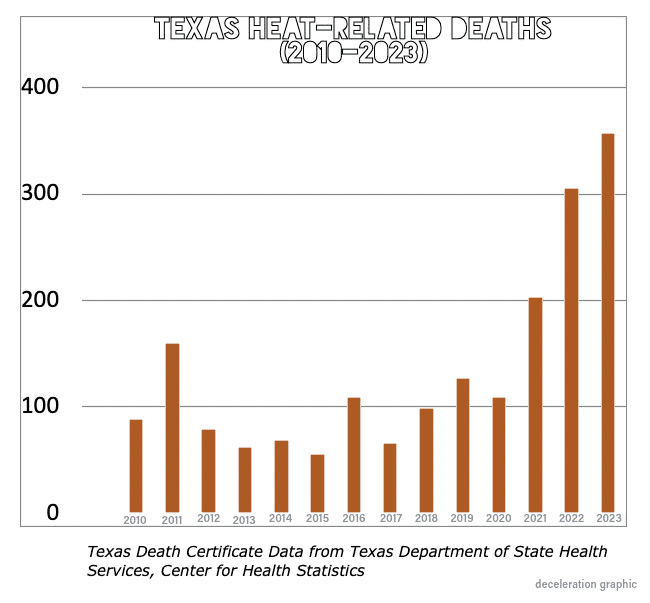

Maldonado’s death was one of an estimated 357 heat deaths in Texas last year—the most ever recorded in the state.

While familiar in Texas, heat is an underappreciated killer. It is the most deadly of all weather-related phenomena. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates at least 1,200 people in the country die each year from heat exposure.

Meanwhile, the heat—and resulting heat illness and deaths—is only getting worse.

The last 10 years all rank among the 10 hottest years ever recorded. 2023 was the hottest year on planet Earth in at least 125,000 years. It’s a trend that has not improved even through the winter and spring, as month after month have continued to break records as the hottest respective months ever recorded on the planet.

It’s a five-alarm global heat event that even climate scientists can’t account for.

Yes, it’s fossil fuels driving the bulk of the heat, but the heat is manifesting at an accelerated rate that confounds even the climate models.

In the span of a year, the scientific debate has moved from whether the world can keep global warming to the somewhat arbitrary threshold of an additional 1.5F warming to if the industrial warming of Earth has already “fundamentally altered” the planet’s climate.

Long dragged for failing to advance a national heat standard for workers, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration released new educational resources, including a 30-minute video, in April. The intention is to get ahead of this year’s extreme heat and educate Spanish-speaking laborers, in particular, about heat’s expanding danger. Hispanic men, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data suggests, are some of the most impacted by the heat.

“There are a couple of times a year where we really push our emphasis on heat,” Meghan Forester Christie, OSHA’s assistant regional administrator for state programs, told Deceleration. “We do that in May; there’s a week called ‘No Fry’ week. And in the summer we focus on heat really heavily.”

OSHA’s inspection jurisdiction kicks in anytime the heat index reaches 80 degrees—which is much of the year in Texas.

Leer: Guía de Capacitación sobre Prevención de Enfermedad a causa del Calor (PDF)

A federal heat standard is finally in development. You can track its progress here. But expect this process to take years yet. OSHA’s message in the meantime is a necessary reminder that employers are still responsible under existing law for keeping their employees safe in the heat.

Cities that, in the absence of federal action and faced with the reality of escalating deaths, sought to advance their own heat standards for workers—including Austin, Dallas, and San Antonio—found themselves punched back by Republican lawmakers last year via passage of House Bill 2127, the infamous “Death Star” bill.

On average, OSHA only logs about 33 heat-related deaths among workers per year in the United States. Hardly epidemic material. This figure, however, as OSHA officials acknowledge in a report detailing their current heat standard efforts, is almost certainly a “vast underestimate.”

Heat surveillance around the country is plagued by “inconsistent reporting by medical professionals as a result of varying definitions of heat-related illness by jurisdiction,” that report concludes, as well as “lack of recognition of heat as a causal or contributing factor to injury or illness, underreporting to BLS [U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics] by employers, and workers not reporting injuries or illnesses due to stigma or fear, among other reasons.”

Missing from this list of failures is OSHA itself, which has been criticized for failing to conduct more frequent heat inspections.

Public Citizen, a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization, petitioning for a federal heat standard in 2018 called OSHA’s enforcement on heat “grossly inadequate.” A press release claimed that California, one of five states that have moved forward with their own heat standards, conducted 50 times the number of investigations as OSHA—and banked nearly $12M in fines from violators of that state’s heat standard.

OSHA’s limited engagements, though, have critically shined the light on deaths in Texas that otherwise almost certainly would not have been understood as heat-related.

Such was the case with Maldonado, previously unreported by the media.

The operations manager for the Nueces County Medical Examiner’s Office, Forrest Mitchell, told Deceleration that heat deaths are rarely recorded by his office.

The problem, he suggested, is insufficient local surveillance efforts. While the medical examiner’s staff are equipped with thermometers and are trained to take ambient and core body temperatures (a prerequisite to determine the role of heat in any death) they are rarely the first ones to arrive at the scene of a death.

Data maintained by the Texas Department of State Health Services doesn’t include any heat-related deaths in nearby Matagorda County, where Maldonado died, between 2019 and 2023. Part of the reason could be that county-level reports of fewer than 10 heat-related deaths per year are not included in state data to avoid the release of records that may identify individuals and potentially confidential medical data. But state data also curiously shows no heat-related deaths for any of these years in the much larger Nueces County, home to 315,000-population Corpus Christi.

In Bexar County, the heat-related death of Gabriel Infante was widely reported in 2022 after it was first included within OSHA’s fatality inspection data. To date, that lone 2022 death is almost certainly the source of the only heat-related death ever publicly reported by San Antonio’s Metropolitan Health District. Most years the agency lists deaths as “N/A,” or not available.

The Texas Department of State Health Services, however, lists 28 heat-related deaths in Bexar County between 2019 and 2023. We know even this is also an undercount because, as with her colleague in Corpus Christi, Bexar’s Medical Examiner Kimberley Molina says she rarely lists heat as a cause of death or even as a contributing factor because of what she describes as inadequate heat surveillance by emergency responders.

Related: ‘Heat Emergency—a Forum on Extreme Heat, Public Health, & Community Response‘

Rose Jones, a medical anthropologist who cut her teeth doing outreach among rural and Spanish-speaking communities during the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, said that heat being driven by climate change poses an even greater public health threat.

“What happened last summer was life changing for me,” she said at ‘Heat Emergency,’ a Deceleration community forum on the topic of extreme heat. “I literally watched extreme heat transition from an invisible public health crisis into a full blown humanitarian issue.

“I’ve spent 30 years working within academic community medicine. In HIV, I was there for the early days, and I had not seen during that time anything that is as concerning as what I’m seeing now.”

That conviction inspired her to leave her position with the nonprofit Texas Trees Foundation, where she was helping respond to extreme heat through targeted tree plantings, and form her own initiative, Rapid Anthropology Consulting. The mission of RAC is to “build awareness for change at the intersection of heat + health + equity.”

Texas’s accounting, while woefully insufficient, supports Jones’s concerns of heat being used, essentially, as a weapon of the state to punish entire groups of people, including unhoused, migrants, and the incarcerated.

Data released to Deceleration shows the most recorded heat deaths are being logged in Webb County: 137 of 1,102 logged statewide between 2019 and 2023. Some of these were long-time local residents, as The New York Times highlighted last year. But many are also likely desperate migrants and families squeezed by enhanced border enforcement into more remote pockets of the state.

Though counts for recent years have not been finalized, state data shows roughly 440 of the 1,102 deaths happened in border counties.

In the workplace, OSHA has its work cut out for it.

Texas leads the nation in workplace fatalities. Between 2010 and 2018, Texas averaged about 412 fatal injuries among workers per year.

“We shifted gears this season to create some very specific Spanish content so we can target groups we need to focus on,” said OSHA’s Christie. Even as the heat standard slowly advances, Christie said the agency’s existing general duty rule does not allow for for employers to skirt basic heat protections.

“You’re expected to look at what your employees may be exposed to and be willing to make adjustments as the day goes on,” said Christie. That includes “allow[ing] employees the opportunity to be trained and know when to speak up for themselves when they are experiencing a symptom [of heat illness].”

In Maldonado’s case, the investigation summary shows no penalties or citations levied against employer TM Workzone Masonry.

Bcomm Constructors was fined $13,052 over Infante’s death and issued a “serious” citation. But records show that the citation has since been deleted. His mother sued the company alleging gross negligence in his death.

The rights of the incarcerated were raised in a federal complaint reported by the Texas Tribune recently that alleges inmates in the state being “cooked to death” in extreme temperatures. This is happening as some state lawmakers continue to resist calls for basic cooling in state prisons.

For context, consider that Texas state law sets minimum and maximum temperatures for animal shelters. “The ambient temperature must not fall below 45° F (7.2° C) for more than 2 consecutive hours when dogs or cats are present,” state code reads, “and must not rise above 85° F (29.5° C) for more than 2 consecutive hours when dogs or cats are present.”

As Jones said during Deceleration’s heat forum:

“Two-thirds of the prisons in Texas are not air conditioned. Air conditioning is no longer a luxury item. It is the question of life and death.”

There are innumerable short-term actions required to reduce suffering during this period of expanding heat. Proper accounting of heat’s actual impacts is square one. This is why Deceleration launched a petition to urge Bexar County’s Medical Examiner and San Antonio’s Metro Health to prioritize the tracking and recording of heat deaths.

Petition: Extreme Heat is Killing Us. We Demand a Better Medical Response.

Really, every community should probably do the same.

Then there are the bigger shifts needed to stop the heat from coming so hard in the first place.

The leading role of fossil fuels in this heat is regularly neglected by some popular interpreters of area weather in favor of frequent references to El Niño as a source of added heat. It’s confounding not only for ignoring the smoking gun in the room, but because El Niño, though it does tend to drive up global temperatures, actually has a general cooling influence in Texas most of the year.

“Texas could have been even warmer had it not been for the Pacific El Niño which is known to have cooling impacts over much of the United States,” NASA data scientist Andrey Savtchenko wrote late last year about 2023’s heat.

As Texas A&M-based climate scientist Andrew Dessler rightfully urges Texas residents: “[D]on’t blame El Nino for the scorching heat you’re experiencing. Instead, blame the oil companies.”

We need, in other words, to rapidly transition to a cleaner energy economy to slow the generation of all this extra heat while concurrently investing in better understanding of how this heat is landing so we can interrupt its worst manifestations. Even as the planet’s climate system teeters, we still have an opportunity to save a lot of lives.

If we choose to.

-30-

Like What You’re Seeing? Become a patron for as little as $1 per month. Explore ways to support our mission. Sign up for our newsletter (for nothing!). Subscribe to our podcast at iTunes. Share this story with others.