Unpacking the National Climate Assessment and its call for urgent climate action.

The summer of 2011 should have been a wake-up call for Texans. Not only was there a withering heat driven, in part, by human-caused climate change (remember those record-breaking 40 consecutive days of 100-plus temperatures?) but a crippling drought gripped the entire state. It was the worst one-year drought on record, we’d later find.

Then there were the wildfires. Another best-of among the worst-ofs.

As you would expect, it all put a major strain on the already precious water supplies around the state, which in turn forced the electricity sector into a sweat as air conditioners strained to keep residents from bursting into flames … or at least stave off serious heat stroke.

“Heat, increased evaporation, drier soils, and lack of rain led to higher irrigation demands, which added stress on water resources required for energy production,” the latest National Climate Assessment, released last week, reads. “At the same time, low-flowing and warmer rivers threatened to suspend power plant production in several locations, reducing the options for dealing with the concurrent increase in electricity demand.”

All told, the drought, heat, and fire punished the state to the tune of $8.2 billion in the agricultural sector alone, according to the state comptroller, and ranked among the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s growing list of billion-dollar climate disasters.

According to the most recent assemblage of leading climate science, these sorts of “cascading effects” are only expected to increase. And Texas, coincidentally also the leading greenhouse gas emitter in the nation, is lined up to bear the brunt of it.

While there are many drivers impacting the climate, the third report of the U.S. Global Change Research Program drawing on the work of hundreds of U.S. researchers across more than 800 pages echoes the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in saying that human activity is the main driver behind the ongoing warming that is inspiring everything from longer, drier summers and rising seas to stronger rainfall events and flooding.

I say these colliding and collaboratively crippling weather events should have been a wake-up call because so many of the state’s political leaders even now refuse to cozy up to the report’s takeaway message.

The Texas Observer runs down the denier messages (or in Governor Rick Perry’s case, non-messages) from Texas’ leadership, including U.S. Senator John Cornyn, U.S. Rep. Lamar Smith, and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which Forrest Wilder suggests is “mightily concerned about the coal industry.” And not in a productive way, as far as climate change is concerned.

Why does it matter?

The unmistakable message of the new National Climate Assessment is two-fold: 1) Destabilizing climate change is happening now; and 2) there’s still time to prevent the worst of projected changes for the decades to come.

“Climate change is no longer a future issue,” contributing author Katharine Hayhoe, director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University, told The Dallas Morning News. “We are experiencing its impacts today.”

To date, temperatures have risen between 1.3 and 1.9 degrees on average – mostly since 1970 – and are projected to rise as high as an average of 10 degrees by 2100 if action is not taken to severely limit greenhouse gas pollution from key sources such as fossil-fuel-dependent power plants, mass transportation, and agriculture.

Already the risk of extreme heat events occurring like the one that scorched Texas in 2011 has doubled because of the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

As a fan of graphics (and this report is full of ’em), I’ve been restraining myself. But here are two profoundly important ones.

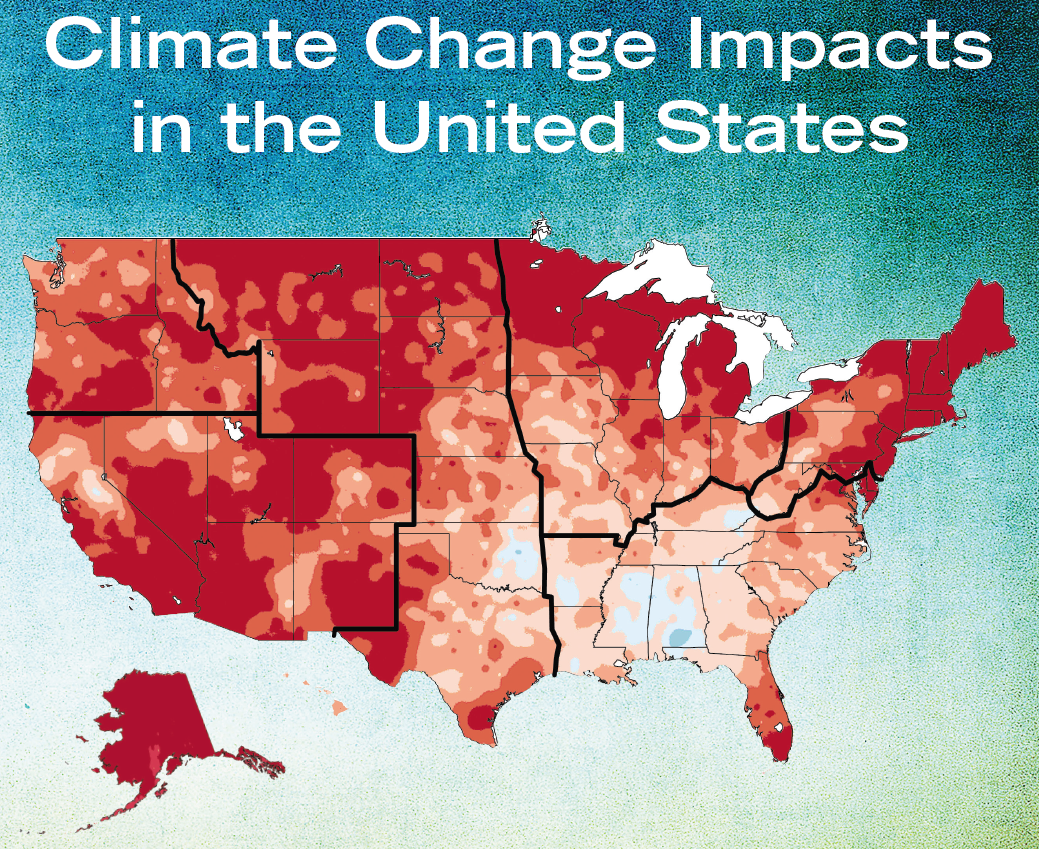

Here’s the increased heat we’ve witnessed so far (while other factors, including solar contributions, have mostly been in decline):

As the assessment makes clear, less than two degrees have brought difficult changes to the U.S. A couple more degrees are projected to bring even more destructive impacts. Beyond that, the research starts to veer into discussions of the collapse of industrial society.

Here’s the expected heat to come by 2100, based on various political responses to greenhouse gas pollution:

That top left outcome is the result if we can cut greenhouse emissions by more than 70 percent by 2050 (and even more in the decades after that). The bleeding map at bottom right assumes continued increases of greenhouse gases through the century.

While some — one economist in particular comes to mind — have insisted researchers “aren’t allowed” to discuss the benefits of all this warming, there are some stated here. All those newly ice-free days will be a boon to shippers on the Great Lakes, the report points out. But the negatives are definitely behind the wheel for now.

Which is what makes the assembled semi-truths promoted by U.S. Rep. Lamar Smith and others so difficult to digest. The day the report came out, Smith put out a press release alleging the NCA “stretched” the truth. I’m not sure who actually reads such press releases in their entirety, but I thought it may be useful to unpack his counter argument point by point.

Smith: The report fails to explain the absence of warming over the last 15 years.

Fact Check: The report does address this frequent objection among the conservative political class.

Consider:

It is true that surface temperature trends have not risen as fast as predicted by some, however, it appears the ocean has absorbed the so-called “missing heat.”

That result appears to be painfully evident in a Kelvin wave now surfacing in the Pacific that has tipped the odds of an El Niño event bringing what is expected to be a another record-breaking year of heat in 2015.

You can see a model of this heat being “belched” into the atmosphere at right, courtesy of Robert Scribbler, who’s done a fair bit of analysis on the event.

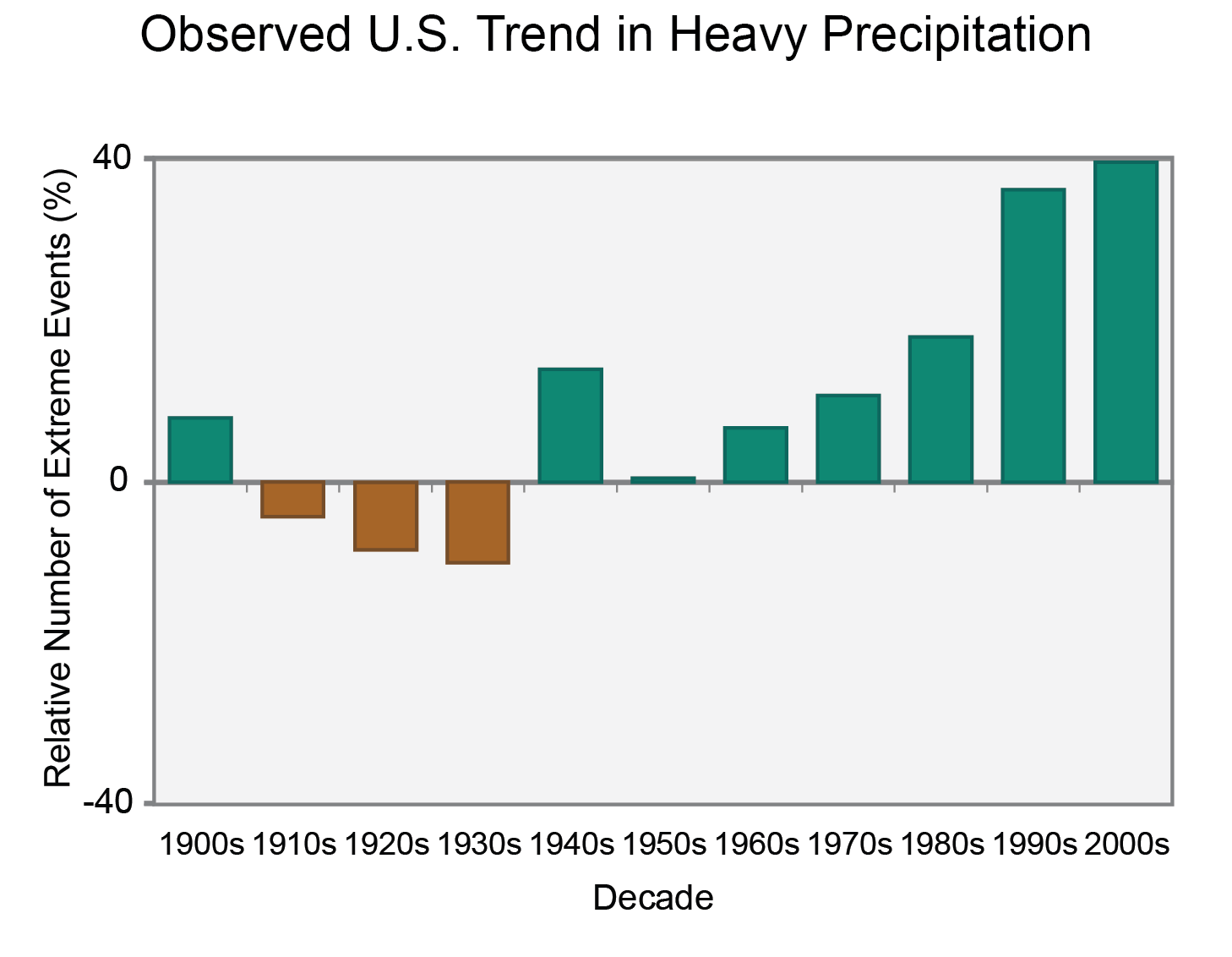

Smith: There is “little science to support any connection between climate change and more frequent or extreme storms.”

Fact Check: Perhaps we need to ask which extreme storms he’s talking about. Maybe it doesn’t matter. All types of storms seem to be increasing. However, the violent rainfall events are the most obvious and troubling, according to the assessment.

Hurricanes remain difficult to link definitively to climate change (though logic dictates a warmer ocean must do something with that contribution, see above). Atlantic storms have increased in “intensity, frequency, and duration.”

And the frequency and intensity of winter weather storms are also fairly obvious, especially in the high latitudes.

Smith: The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) was “critical” of the draft National Climate Assessment. (He then sites multiple examples of this allegedly critical stance.)

Assessment: Judging from Smith’s assertions that anthropogenic climate change is not a dominant force today one may assume he’s suggesting the NAS is critical of some fundamental element of climate science as presented in the NCA. That isn’t the case. Climate change been a front-burner topic with the nation’s premier scientific body for years.

And here again NAS report authors restate the consensus view that:

While scientists continue to refine projections of the future, observations unequivocally show that climate is changing and that the warming of the past 50 years is primarily due to human-induced emissions of heat-trapping gases. These emissions come mainly from burning coal, oil, and gas, with additional contributions from forest clearing and some agricultural practices.

Of course, one would expect some points of correction and direction in any thorough scientific review — such is a huge part of the scientific process — and this one has them scattered across 90 pages. But to gauge the group’s overall disposition on the whole we don’t need to go that deep.

Consider the Executive Summary, which states:

Given the current state of the science and the scope of resources available, we believe the NCA did a reasonable job of fulfilling its charge overall. … As the nation continues to engage with the threats, opportunities, and surprises of climate change in its many manifestations, the 2013 NCA should prove to be a valuable resource, as a summary of the state of knowledge about climate change and its implications for the American people.

Sounds almost flattering.

Moving forward to the Introduction:

With a report as large and diverse as this one, the answers to these questions were naturally a complex mix of positive reactions for some parts of the report and less positive reactions for other parts. …

We wish to acknowledge the tremendous amount of work that has gone into the preparation of the NCA report, and likewise to acknowledge that this NCA has been a significantly more ambitious effort than previous National Climate Assessments, in terms of the scope of topics addressed and the breadth of outreach/engagement processes involved. We offer our congratulations to the NCA leadership and authoring teams for their accomplishments thus far, and our sincere hope that the suggestions offered herein will aid their efforts.

For what it’s worth, respected environmental reporter Seth Borenstein at the AP looked at Smith’s objections and dismissed them.

This assessment four years in the making is more than merely a “White House” report, as Smith calls it. It is the summation of a huge amount of research by more than 300 researchers working with a 60-member advisory committee with most of its 3,096 footnotes marking published peer-reviewed scientific research.

What actually becomes of the report in the face of still largely divided voting public remains to be seen. But one thing is clear: Today’s delay will be certainly measured in degrees.