This month Deceleration is traveling and reporting back! Greg will be in Ecuador for a three-week intensive course on environmental peacemaking, while I just returned from Detroit, where I attended a meeting of the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment (ASLE) at Wayne State University, presenting a paper on the vision and praxis of Deceleration.

Despite a name that suggests a narrowly academic focus on literary studies, ASLE actually draws a fairly expansive and eclectic bunch. Over a span of just a couple days, I met popular science writers, filmmakers, activists, poets, and students as well as literature and creative writing instructors across a variety of institutions (from online teaching to community colleges to more traditional sorts of universities). But what drew us together was an interest in the cultural aspects of human relations to nature. If the environmental sciences seek to document and quantify human impacts on nature, the environmental humanities is centrally concerned with how we think about and imagine nature, and how these cultural imaginaries in turn shape how we then relate to nature, for better or worse.

However, the very best panels I attended were those in which people spoke to each other across not only academic disciplines–bringing the sciences and humanities into conversation–but, more fundamentally, across institutions. (Conversely, the worst panels I attended were those where five people all presented analyses of literary texts). It’s fairly easy to be interdisciplinary nowadays, and in fact the consensus within the environmental humanities is that environmental crises, more than most things, require all disciplinary hands on deck. As French science studies guy Bruno Latour observed way back in 1989 in We Have Never Been Modern, the proliferation of “hybrid objects” (things that mix up the “cultural” with the “natural” such as GMOs or Hurricane Katrina) is historically and ecologically unprecedented. In Latour’s time, the fall of the Berlin Wall signaled the global victory of capitalism, while in the same moment the discovery of a hole in the ozone layer over the Antarctic simultaneously signaled the fundamental untenability of that victory. For Latour, it is the rule of capital/death of nature which hyperproduces hybrid objects like the ozone hole–since ameliorated, only to be replaced by the even vaster crisis of climate change–which link together politicians, environmentalists, scientists, doctors, cultural critics, and activist groups, as well as the earth’s millions of non-human species. The hybrid objects of environmental concern, then, cannot be understood via a knowledge system that separates out “a natural world that has always been there, a society with predictable and stable interests and stakes, and a discourse that is independent of both reference and society” (11). Faced with the prospect of a collapsing biosphere, all knowledge and ways of knowing will become necessary.

So interdisciplinarity is the consensus, at least in theory. What’s much harder, though, is to be inter-institutional, bringing conversations across the sciences, social sciences and humanities into conversation with activist and artistic knowledge and ways of knowing. This is hard because it requires not simply that we collaborate intellectually but that we move our bodies, shifting the physical location of our commitments. It requires real movement outward into the world: perhaps into the space of the meeting or public hearing, perhaps into a neighborhood not one’s own, perhaps into another way of working, perhaps in the process giving up one’s position altogether or ceding one’s authority. And yet this is precisely the kind of radical epistemological shift that is going to make a difference.

I came to these thoughts after I had the opportunity to attend an amazing panel called “Detroit Water Wars: Empire and Ecology in the Postindustrial Heartland.” Featuring an historian, two environmental toxicologists, two Detroit activists and a hip hop artist, this panel helped situate water issues in the Great Lakes area in their scientific and historical context, but also in connection to contemporary struggles around water in Detroit, as expressed in activism and art. I came to this panel as someone who had never been to Detroit, someone from a very different climate, bioregion, and watershed, who has only heard stories on the news about Flint and the wreckage left behind in Detroit by the collapse of the auto industry and subsequent emergency financial management. And yet so much was familiar too–the description by Mother Taylor and Monica Lewis-Patrick of the devastating impact of water shut-offs on poor families in Detroit reminded me of San Antonio, as Monica and I begin to discuss in the short video below. We hear about Flint, but we don’t hear the stories of people like my next-door neighbors, quietly living for six months without water or electricity or income to turn them back on.

Setting up the panel was David Watson, Detroit-based author, activist, and prep school Spanish teacher(!), who situated the ecology of the Great Lakes within the context of empire and colonial settlement. First active in struggles over nuclear power and incineration, Watson described fighting “a way of life that was, in dialectical fashion, a way of death,” in which sacred places became waste dumps. Recovery of the sacred thus “relies on a relentless critique of empire.” Recalling the metaphorical centrality of water to justice struggles in MLK’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, Watson concluded his framing remarks by saying that if we are to realize “justice run[ning] down like water,” we must bring justice to the water as well.

Following Watson, the next two speakers were environmental toxicologists from Wayne State University, Donna Kashian and David Pitts, who together gave an historical and scientific overview of contamination in the Great Lakes. Donna Kashian began with some history that was as endlessly fascinating as it is familiar to me, given my dissertation research on the ecological politics of poop–the mass adoption of the flush toilet, which made human concentration in urban centers possible by allowing for the rapid removal of waste. However, the flush toilet also became the technological linchpin for treating the Great Lakes as a waste sink, inaugurating an “out of sight, out of mind” relationship to waste culturally, along with scientific assertions that “dilution is the solution to pollution.”

While this may have been true for early industrial wastewater streams, whose chief problem was the pathogens in poop, the 20th century saw the introduction of chemical discharges from industrial facilities that has only gotten more complex into the 21st. Modern wastewater treatment plants are designed to strain out biological contaminants to water, which they do quite well; however, as explained by David Pitts, what they leave behind is an alphabet soup of endocrine-disrupting chemical contaminants like BPA and PCBs, not to mention pharmaceuticals (especially psychoactives, which have been found in the brains of fish), nano-materials, and micro-plastics. Kashian pointed out that those of us born in the 1970s through the 1990s are the first generation exposed to anthropogenic chemicals both within the womb and post-natally.

After the scientists, two long-time Detroit activists spoke: Maureen D. Taylor, State Chair of the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, and Monica Lewis-Patrick, President of We the People of Detroit Research Collective. Taylor began by describing how, in the 1950s, Detroit had a population of 1.8 million, buyoed by the booming auto industry. It was “Motor City,” destination for many African Americans fleeing the Jim Crow South. Following the collapse of this industry, Emergency Financial Management (EMF) was instituted in 2013 and the city soon after filed for bankruptcy. Detroit’s Population plummeted to 700,000, a loss of more than 1 million people “because they couldn’t maintain a standard of living.” As people left, Taylor stated, “civility declined,” symbolized most in the brutality of water and gas shut-offs under EMF for those who could not pay their utility bills. As Taylor and other activists discovered, 59,000 people were on the list for shut-offs, which then became a tool of family separation and home seizure. “After 72 hours with no water,” she said, “CPS can come in and take your children.” Without utilities, families were also at risk of having their homes taken via eminent domain.

In response, Taylor and others helped formed the People’s Water Board, “a coalition,” according to their website, “of three dozen Southeast Michigan organizations (anti-poverty, social justice, environmental, conservation, faith-based) working together to protect our water from pollution, high water rates, privatization; and the denial of water and sanitation services to people unable to afford it.”

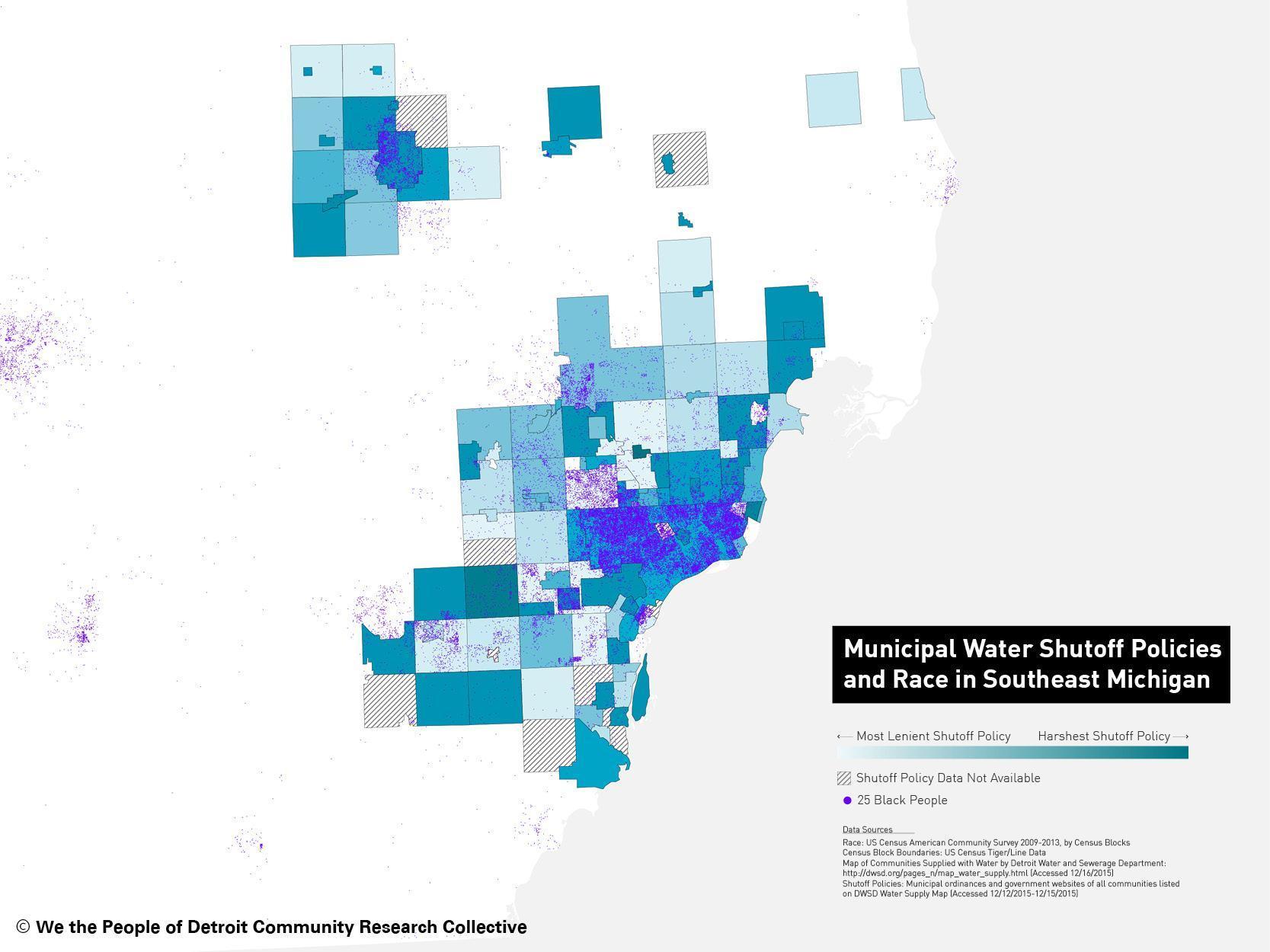

Similarly, Monica Lewis-Patrick discussed how the work of We the People of Detroit started around the effects of emergency management on public education, but shifted to water access after Charity Hicks, a community leader and water protector who passed in 2014, was arrested for speaking out against the shut offs in her neighborhood. Via the People’s Water Board, Lewis-Patrick, Taylor, and numerous others organized a hotline for reporting shut offs, emergency water stations, and community research efforts to document the extent of the crisis, even publishing a book last year on the basis of this research, entitled “Mapping the Water Crisis: The Dismantling of African American Neighborhoods in Detroit.” Lewis-Patrick spoke powerfully about how, out of 126 municipalities in the region, Detroit and Flint, communities with large Black populations, were the only two with a water shut-off policy for delinquency. “This is not conspiracy,” she said. “This is a highly orchestrated system of evil to determinate who can drink and who cannot.”

The final speaker on the panel was William Copeland of East Michigan Environmental Action Council, who identified himself as a cultural activist and hip hop artist and also invoked the memory of Charity Hicks as an ancestor. “We’ve gone through a lot of technical information get to this point,” he said, before presenting verse from his track “Emergency/EMF.” Originally a Ph.D. student in Philosophy at the University of Michigan, Copeland described wanting to be the next Cornel West, until he realized that art, and hip hop specifically, was the more profound vehicle for community education (as suggested by West himself, who has released three hip hop albums, as Copeland laughingly acknowledged).

Having been on both sides of the academic/activist dialectic, I know how great the temptation can be to engage in a kind of reverse dismissal of academic knowledge–to treat grassroots knowledge as the real expertise, more authentic and real than what comes out of that ivory tower. Copeland himself came close to this (“We’ve gone through a lot of technical information to get to this point.”). And yet the great power of the “Detroit Water Wars” panel lay precisely in its inter-institutionality, its bringing together not only the sciences and the humanities and the social sciences but also the academic with the activist with the artistic. There is a need to defend the legitimacy of grassroots knowledge as expertise, no doubt. But in an era of hybridized objects, all kinds of knowledge will be necessary.

And yet. There is something that art can do that analysis and activism cannot on its own. Call it the power to move, to integrate, to unify. A panel that featured the scientists and the historians and the activists would have been plenty good. But Copeland wrapped up by playing “Nakweshkodaadiidaa Ekoobiiyag [Let’s Meet Up by the Water]” for the ASLE audience, a track by Detroit hip hop artist Sacramento Knoxx–ending with a knowledge and way of knowing that made a whole of disparate parts in a way nothing else could have done:

Afterwards I had the opportunity to briefly interview Monica Lewis-Patrick, featured in this track as spoken word artist. Frustratingly, after we spoke for a good ten minutes, I realized that my phone had stopped recording, and assumed it had never begun recording at all due to a full memory card. Upon arriving home, I was delighted to find that I managed to get the first three minutes of our conversation. Though embarrassed that so much of this time is taken with my very long-winded question, I post it here nonetheless because I love that she opens her words with love from Detroit for San Antonio. I post it here too as a hint of things to come for Deceleration–in the next few weeks, be on the look out for a podcast with Monica!